|

Alan Kreuger (author, with Card, of widely cited study showing no unemployment from a minimum wage hike) weighing in on a $15 dollar minimum wage. The Minimum Wage: How Much Is Too Much? By ALAN B. KRUEGER OCT. 9, 2015 THE federal minimum wage has been stuck at $7.25 an hour since 2009. While Congress has refused to take action, Democratic politicians have been engaged in something of a bidding war to propose raising the minimum wage ever higher: first to $10.10, then to $12, and now some are pushing for $15 an hour. Research suggests that a minimum wage set as high as $12 an hour will do more good than harm for low-wage workers, but a $15-an-hour national minimum wage would put us in uncharted waters, and risk undesirable and unintended consequences. When Congress delays raising the minimum wage, states and cities typically step in and raise their own minimum wages. That is exactly what is happening now. More than half of the states, representing 60 percent of the United States population, now have minimum wages that exceed the federal level. The fact that voters in four “red” states — Alaska, Arkansas, Nebraska and South Dakota — voted overwhelmingly last year to raise their states’ minimum wages to as high as $9.75 an hour is a testament to the support the minimum wage enjoys among the population at large. Some cities plan to raise their wage floors to $15 an hour. And Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo declared last month that “every working man and woman in the state of New York deserves $15 an hour as a minimum wage.” When I started studying the minimum wage 25 years ago, like most economists at that time I expected that the wage floor reduced employment for some groups of workers. But research that I and others have conducted convinced me that if the minimum wage is set at a moderate level it does not necessarily reduce employment. While some employers cut jobs in response to a minimum-wage increase, others find that a higher wage floor enables them to fill their vacancies and reduce turnover, which raises employment, even though it eats into their profits. The net effect of all this, as has been found in most studies of the minimum wage over the last quarter-century, is that when it is set at a moderate level, the minimum wage has little or no effect on employment. For example, David Card of the University of California, Berkeley, and I found that when New Jersey raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05 an hour in 1992 (or from about $7.25 to $8.60 in today’s dollars), job growth at fast-food restaurants in the state was just as strong as it was at restaurants across the border in Pennsylvania, where the minimum wage remained $4.25 an hour. Equally important — but less well known — within New Jersey, job growth was just as strong at low-wage restaurants that were constrained by the law to raise pay as it was at higher-wage restaurants that were not directly affected by the increase since their workers already earned more than the new minimum. I am frequently asked, “How high can the minimum wage go without jeopardizing employment of low-wage workers? And at what level would further minimum wage increases result in more job losses than wage gains, lowering the earnings of low-wage workers as a whole?” Although available research cannot precisely answer these questions, I am confident that a federal minimum wage that rises to around $12 an hour over the next five years or so would not have a meaningful negative effect on United States employment. One reason for this judgment is that around 140 research projects commissioned by Britain’s independent Low Pay Commission have found that the minimum wage “has led to higher than average wage increases for the lowest paid, with little evidence of adverse effects on employment or the economy.” A $12-per-hour minimum wage in the United States phased in over several years would be in the same ballpark as Britain’s minimum wage today. But $15 an hour is beyond international experience, and could well be counterproductive. Although some high-wage cities and states could probably absorb a $15-an-hour minimum wage with little or no job loss, it is far from clear that the same could be said for every state, city and town in the United States. More logical is the proposed legislation from Senator Patty Murray, Democrat of Washington, and Robert C. Scott, Democrat of Virginia, calling for raising the federal minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2020. Their bill is co-sponsored by 32 senators, and supported by President Obama and Hillary Clinton. High-wage cities and states could raise their minimums to $15. Although the plight of low-wage workers is a national tragedy, the push for a nationwide $15 minimum wage strikes me as a risk not worth taking, especially because other tools, such as the earned-income tax credit, can be used in combination with a higher minimum wage to improve the livelihoods of low-wage workers. Economics is all about understanding trade-offs and risks. The trade-off is likely to become more severe, and the risk greater, if the minimum wage is set beyond the range studied in past research. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/11/opinion/sunday/the-minimum-wage-how-much-is-too-much.html?_r=0

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 18, 2024 10:38 |

|

Is there any evidence of states responding to federal minimum wage hikes? Do they usually?

|

|

|

|

Responding how? By raising their own minimums? I don't think so.

|

|

|

|

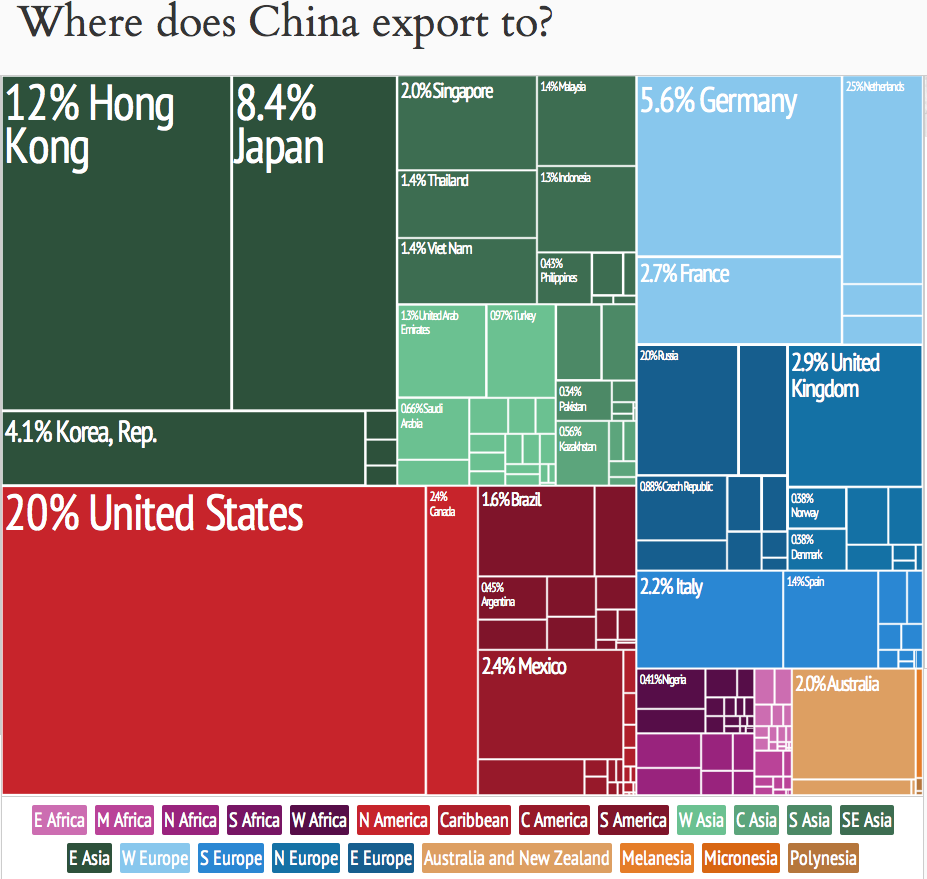

Helsing posted:This thread kind of dropped of my radar so I didn't realize anybody had responded to my posts. Apologies this is coming in late. I don't know why you think U.S. aggregate trade surplus is relevant to China which cares about what the U.S. is buying from them. I want to point out a few things. First, the U.S. isn't as large a percentage of Chinese trade as you may thin. Looking at the chart below you see large squares for other net exporters like Japan and Germany. On the whole, China exports more to the E.U. than to the U.S. and the E.U. is itself a net exporter.   quote:Without the United States acting as the buyer-of-last resort I'm not sure how successful various export oriented economies would have been. In a sense the US economy has been stimulating the rest of the global economy with its large trade deficit which is not necessarily the most balanced or desirable path for global growth. Not true given that the U.S. is only 20% of China's exports and I don't know what you're trying to capture with "buyer of last resort". The U.S. isn't deliberately doing any favors by buying Chinese stuff. I'll assume you're probably implying that U.S. trade deficits aren't sustainable. I don't think that's true in the short or medium term (because of the unique place the dollar has in the world economy which holds up its value). But it doesn't really matter. quote:Well then answer my original question: "If we imagine a world where China and the US aren't juicing their economies and buying up so much of what the rest of the world sells then what might the world economy look like right now?" I don't think juicing is a thing and I don't think there is anything that's going to bring an end to high levels of Chinese trade. What I take you to be implying is that Chinese growth isn't sustainable or isn't more widely applicable. I disagree. At the most basic level trade driven growth is about comparative advantage. It's about trading low skill labor for volumes of higher tech capital. It's not about finance or best explained in terms of finance. As long wage differentials exist there is motivation for rich countries to outsource labor in a way that induces trade. This is fundamentally sustainable and works under a wide range of specific conditions in terms of who the buyers and sellers are, what the specific surpluses are etc. quote:Around the middle of the 1970s economic growth in the developed areas of the world slowed dramatically, and the postwar Bretton Woods system broke down. One of the responses that the share of GDP going toward financial activities began to increase significantly. Since this process of 'financialization' began some forty years ago the economy has behaved differently than it did in the past, with growth tending to produce unstable bubbles that inflate and inflate until they collapse and trigger a major crisis. It's not internally consistent to correctly categorize bubbles as destructive yet credit them with growth. Bubbles are market failures. They represent misallocations of capital which only look beneficial while they're happening and then are clearly destructive when they pop. They don't benefit anyone in the long run. You're correct to correlate growth and bubbles because that's what history demonstrates. Bubbles are helped by the dynamism that often accompanies growth. But bubbles are only parasitic in that process. I don't know what your question is intending to mean. The U.S. is world's largest source of research and development (notably technology and drugs) and China is the world's largest manufacturer. That's what they mean to the world economy and these are desirable things. The U.S. is slowly receding in terms of its share of the world economy and China is growing. There is nothing fundamentally unsustainable about either thing.

|

|

|

|

My takes on some of your questionsVeskit posted:

No unless they were doing extremely poorly but the board wouldn't remove them for whatever reason. There's a perception that good executives are crucial to a company running well and getting a good shareholder value, drat the costs. quote:

quote:

quote:

quote:

Homura and Sickle fucked around with this message at 09:37 on Oct 10, 2015 |

|

|

|

Regardless of the proportion of stock held by executives and the board, large proportions of shares are held by institutional investors and they move basically with the wind- they only vote to oust or whatever when it's practically a fait accompli. Shareholder democracy is a fairly incoherent idea in and of itself, but the way in which stocks are held makes it largely dead.

|

|

|

|

|

JeffersonClay posted:Alan Kreuger (author, with Card, of widely cited study showing no unemployment from a minimum wage hike) weighing in on a $15 dollar minimum wage. Good quote but I think she's missing the political aspect of this one. Labor advocates have learned to demand large min wage increases because it is raised so infrequently. $15 an hour may cause a drag on employment now but in 15 years $12 could well be inadequate. Business pitches such a massive fit over any wage increase and Congress has become so reliably dysfunctional that you have to think ten years into the future with these bills.

|

|

|

|

Arglebargle III posted:Good quote but I think she's missing the political aspect of this one. Labor advocates have learned to demand large min wage increases because it is raised so infrequently. $15 an hour may cause a drag on employment now but in 15 years $12 could well be inadequate. Business pitches such a massive fit over any wage increase and Congress has become so reliably dysfunctional that you have to think ten years into the future with these bills. That's terrible political strategy. Raising minimum wage to a level that will be a drag on employment makes the next attempt to raise it that much harder (hell, if there were actual studies/evidence showing that the last minimum wage hike hurt employment that could kill another attempt to hike it for a whole generation). Instead, you raise it to the level that won't be a drag on employment, while also pegging it to inflation so you never have to go through this fight again.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:I don't know why you think U.S. aggregate trade surplus is relevant to China which cares about what the U.S. is buying from them. I want to point out a few things. First, the U.S. isn't as large a percentage of Chinese trade as you may thin. Looking at the chart below you see large squares for other net exporters like Japan and Germany. On the whole, China exports more to the E.U. than to the U.S. and the E.U. is itself a net exporter. The fact that one dollar of exports out of every five is going to the United States is a massive figure. Obviously China has other important trade partners but the numbers you just provided seem to illustrate how crucial the Chinese-US trade relationship is for Chinese growth and development. quote:Not true given that the U.S. is only 20% of China's exports and I don't know what you're trying to capture with "buyer of last resort". The U.S. isn't deliberately doing any favors by buying Chinese stuff. My comment has less to do with the sustainability of America's trade deficit and more to do with China's reliance on exports. I think the long term consensus is that a balanced Chinese economy would have a much larger domestic market for its own goods but making that transition is a very tricky one. quote:I don't think juicing is a thing and I don't think there is anything that's going to bring an end to high levels of Chinese trade. The US economy is so unbalanced right now and Congress is so dysfunctional that the only way to restore economic growth has been printing huge sums of money to buy up financial assets. The economy is so moribund that this hasn't lead to widespread inflation but it's pushing the price of stuff like housing well above where it otherwise would be and generally making it very hard to know how various assets will be valued once quantitative easing tapers off. I'm obviously not some kind of free market purist who thinks there's some 'true' price for assets that quantitative easing is distorting but what this amounts to is the US Fed taking aggressive and unorthodox measures to prop up an otherwise very weak economy. So I suspect what we'll discover once quantitative easing tapers off is that many US assets are currently priced at levels that will no longer make sense in the absence of quantitative easing. Indeed we may discover that once again the US economy has gone into bubble territory (does anyone think all those tech companies that never turn a profit are being valued accurately right now?). In China we have even less sense of what happens behind closed doors but certainly there are all kinds of implicit guarantees, backdoor deals and outright corruption underlying Chinese growth. China has shitloads of domestic debt piling up and it's not clear how much of that debt was extended for financial reasons vs. how much of it was essentially a political transfer of wealth. Then on top of that we have the government's absolutely enormous post-2008 stimulus plan which involved really massive spending on investments to maintain demand for Chinese products after the western economies slowed down. What this amounts to is that the world's two largest economies, who are themselves locked symbiotically together, are both relying very heavily on unorthodox and largely opaque policies to stimulate growth. And in addition to this both economies are riven with cronyism and corruption, making them even less accountable and even harder to accurately monitor or asses. I don't think anyone fully knows how badly distorted the value of Chinese assets is but there's a growing consensus that a lot of Chinese debt is none-performing and that a lot of Chinese assets are over valued. Likewise it's very hard to say just how stable the US economy would be in the absence of quantitative easing but it may well be that the economy would collapse back into recession without it. quote:What I take you to be implying is that Chinese growth isn't sustainable or isn't more widely applicable. I disagree. At the most basic level trade driven growth is about comparative advantage. It's about trading low skill labor for volumes of higher tech capital. It's not about finance or best explained in terms of finance. As long wage differentials exist there is motivation for rich countries to outsource labor in a way that induces trade. This is fundamentally sustainable and works under a wide range of specific conditions in terms of who the buyers and sellers are, what the specific surpluses are etc. I'm not saying there's something in particular that is wrong with export-oriented industrialization strategies - I think that under the right conditions such a strategy can obviously be successful in building a developed economy. Rather my comment is on the unbalanced and precarious nature of global growth in general. quote:It's not internally consistent to correctly categorize bubbles as destructive yet credit them with growth. Bubbles are market failures. They represent misallocations of capital which only look beneficial while they're happening and then are clearly destructive when they pop. They don't benefit anyone in the long run. (As a side comment I think it's naive to claim no one benefits from bubbles because that's demonstrably false, there are people who came out of the 2008 housing bubble much richer or with much greater market shares than before). I don't think it's internally inconsistent to suggest that capitalism produces dramatic but crisis-prone growth. If you don't want to take Karl Marx's word for it go read Hyman Minsky. This goes back to my previous comment about the move toward financialization since the 1970s. As the financial industry has replaced manufacturing as the central motor of the economy and as debt has started to replace wages as the main driver of consumer demand we've seemingly entered a situation where no economy can grow for a sustained period of time without inflating huge asset or commodity bubbles. This was perhaps less true during the Bretton Woods era when strict capital controls and strong regulatory national governments behaved very differently but in the post-70s world I can't think of any examples of countries that grew at a large and sustained rate without falling prey to very serious bubbles. Can you? quote:I don't know what your question is intending to mean. The U.S. is world's largest source of research and development (notably technology and drugs) and China is the world's largest manufacturer. That's what they mean to the world economy and these are desirable things. The U.S. is slowly receding in terms of its share of the world economy and China is growing. There is nothing fundamentally unsustainable about either thing. (Well actually they are utterly environmentally unsustainable and the relationship is creating a toxic political backlash but that's really neither here nor there in this discussion.) In terms of what we're talking about : I can only say that you seem to have a vastly more positive assesment of how stable the world economy is right now. I look at China and America and see two economies being propped up by extremely nervous governments. In both China and America I think there's a lot of fear that without substantial government stimulation their economies would collapse. And taking a step back, I see a world economy that is so unbalanced that it's virtually impossible to create sustained growth at the national level without relying on the irrational exuberance of investors, which leads to a sort of Casino capitalism effect where huge reserves of global capital slosh around the world economy, pumping up various economies and then crashing them again. So the Greeks get a good decade and then they're hit with a Great Depression level economic catastrophe: Japan grows at a steady clip for decades and is seen as the next world power only to crash headlong into two decades and counting of economic stagnation, the US is heralded as the powerhouse economy of the 1990s and yet, by the mid 2000s, is caught in the midst of the worst economic crisis it has faced in more than half a century, threatening to bring down much of the global economy with it. I'd love to be proven wrong if you have counter examples - that was my original question, after all. EDIT - Had to fix some dyslexic typos. Helsing fucked around with this message at 21:38 on Oct 10, 2015 |

|

|

|

e_angst posted:That's terrible political strategy. Raising minimum wage to a level that will be a drag on employment makes the next attempt to raise it that much harder (hell, if there were actual studies/evidence showing that the last minimum wage hike hurt employment that could kill another attempt to hike it for a whole generation). Instead, you raise it to the level that won't be a drag on employment, while also pegging it to inflation so you never have to go through this fight again. The trouble here is that in the long run there's a basic conflict in the economy between how surplus production is allocated. If you want to reverse the general trend of the last few decades, in which a greater share of GDP goes to capital and a smaller share goes to labour, then you can't rely on a simple technical fix like a minimum wage pegged to inflation. Ultimately the shift from wages to profits is a byproduct of the greater power of capital and the reduced political power of labour. If you don't have some form of institutional representation for labour (traditionally this was Big Labour and their political allies, especially within the Democratic Party) then there's always going to be this inescapable tidal pull toward reducing compensation in real terms. The economy is a pereptual series of conflicts between interest groups and if one interest group (capital, or creditors, or whatever) becomes vastly stronger than another (labour, or debtors, or whatever) then you can expect that the stronger side will find ways to increase their wealth in real terms, and the weaker side will see their wealth reduced. You might be able to counter this trend temporarily under the right circumstances but in the longer run I don't think this is avoidable. Basically minimum wage laws can't replace the existence of an actual labour movement or a labour back political party. There's no technical fix for what is fundamentally a conflict of interests.

|

|

|

e_angst posted:That's terrible political strategy. Raising minimum wage to a level that will be a drag on employment makes the next attempt to raise it that much harder (hell, if there were actual studies/evidence showing that the last minimum wage hike hurt employment that could kill another attempt to hike it for a whole generation). Instead, you raise it to the level that won't be a drag on employment, while also pegging it to inflation so you never have to go through this fight again. This presumes that the point at which the minimum wage becomes a drag on employment is necessarily a functional minimum wage, that is a "living wage", which is not obvious. Neither is the presumption that minimizing drag on employment should be the primary purpose of labor laws.

|

|

|

|

|

Effectronica posted:This presumes that the point at which the minimum wage becomes a drag on employment is necessarily a functional minimum wage, that is a "living wage", which is not obvious. Neither is the presumption that minimizing drag on employment should be the primary purpose of labor laws. A policy which increases wages without affecting employment is unambiguously good. A policy which trades increased wages for increased unemployment can actually make the poor worse-off, depending on the relative magnitude of the increases. Another way of reading krueger's piece is "don't use my research to argue a $15 minimum wage won't cause unemployment because it doesn't support your conclusion"

|

|

|

JeffersonClay posted:A policy which increases wages without affecting employment is unambiguously good. A policy which trades increased wages for increased unemployment can actually make the poor worse-off, depending on the relative magnitude of the increases. Sure, sure, we can reasonably say that once you reach the point of drag on employment, there's a sudden crash such that it's better to have 35 million people on the edge of desperation than not. This is certainly far more reasonable than suggesting a still-inadequate $15/hr minimum wage would have marginal effect on employment. Indeed, one might say infinitely so, if that weren't taken up by appealing to authority's halcyon place at the apex of reasonable.

|

|

|

|

|

Helsing posted:The fact that one dollar of exports out of every five is going to the United States is a massive figure. Obviously China has other important trade partners but the numbers you just provided seem to illustrate how crucial the Chinese-US trade relationship is for Chinese growth and development. You're surprisingly negative about American economy given how it compares to other rich nations right now, notably Europe. Well the fact that inflation isn't high sort of contrasts with the idea that that there is mounting asset bubble. And setting aside our recent housing based financial crash it's otherwise a bit difficult to link housing with other narratives like quantitative easing because of the amount of special attention housing gets (fannie, freddie, tax credits etc). quote:I'm obviously not some kind of free market purist who thinks there's some 'true' price for assets that quantitative easing is distorting but what this amounts to is the US Fed taking aggressive and unorthodox measures to prop up an otherwise very weak economy. So I suspect what we'll discover once quantitative easing tapers off is that many US assets are currently priced at levels that will no longer make sense in the absence of quantitative easing. Indeed we may discover that once again the US economy has gone into bubble territory (does anyone think all those tech companies that never turn a profit are being valued accurately right now?). Well crappy tech startups are a bubble in my opinion but hopefully a minor one and I've always found housing price growth rates to be alarming but with otherwise low inflation it's hard to think we have a terribly large mounting bubble. Quantitative easing is pretty logical policy during times of slack demand and low inflation and it's reasonably straightforward to see that as inflation ticks up it's time to end it. I don't necessarily see cause for concern (qualified by large amounts of uncertainty that acompany any economic prediction). quote:In China we have even less sense of what happens behind closed doors but certainly there are all kinds of implicit guarantees, backdoor deals and outright corruption underlying Chinese growth. China has shitloads of domestic debt piling up and it's not clear how much of that debt was extended for financial reasons vs. how much of it was essentially a political transfer of wealth. Then on top of that we have the government's absolutely enormous post-2008 stimulus plan which involved really massive spending on investments to maintain demand for Chinese products after the western economies slowed down. Well I'll say that I don't feel confident that I understand the inner workers of the Chinese government and it's clear that all of China's growth hangs off their decisions. But in the big picture China isn't greece. Their growth has been the result of them building things and the result of them putting people to work in increasingly skilled and productive ways. That is sustainable growth and I tend to think that even if they have a crash they'll be able to weather it. quote:I'm not saying there's something in particular that is wrong with export-oriented industrialization strategies - I think that under the right conditions such a strategy can obviously be successful in building a developed economy. Rather my comment is on the unbalanced and precarious nature of global growth in general. Well that's not a terribly interesting thought because everything benefits someone even if it's the morgue in a plauge. The inconcistent part would be to imply that the bubble get any credit for the growth. There is a suble difference between that and noting a correlation. The economy doesn't benefit in the long term by employing 100's of skilled workers to develop pets.com before throwing it in the toilet. quote:This goes back to my previous comment about the move toward financialization since the 1970s. As the financial industry has replaced manufacturing as the central motor of the economy and as debt has started to replace wages as the main driver of consumer demand we've seemingly entered a situation where no economy can grow for a sustained period of time without inflating huge asset or commodity bubbles. This was perhaps less true during the Bretton Woods era when strict capital controls and strong regulatory national governments behaved very differently but in the post-70s world I can't think of any examples of countries that grew at a large and sustained rate without falling prey to very serious bubbles. Can you? Well as a really long aside my economic thinking originates from summers spent playing starcraft while watching the History Channel play endless loops of WWII documentaries. This has to do with economics because the overarching narrative of WWII was supply. It was the economies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union which won the war. War time distils economics down to it's most base components. It takes capital and labor to produce a tank and it takes capital and labor to produce a plane. No amount of financial shenanigans in the world can substitute for the massive quantities of steel and 1000's of skilled man-years that it takes to build a ship. When a wartime nation's currency plummets in value due to inflation it's the result of the economy running out of it's core ingredients, not the cause of it. The sort of layman's understanding of financial demand obfuscates this in multiple ways. First it simplifies the incredible complexity inherent to a large economy. Consider the number of people sitting in planning offices coordinating the movement of supplies like toothpaste, chocolate bars, 100's of types of ammunition and 1000's of spare parts around the globe during the war. When you hand a dollar to a cashier all that complexity sits behind your demand for the good. But it complicates the basics with quickly impenetrable layers of mathematical complexity. I can't see big picture economic stuff from quite the same perspective here. I see both the U.S. and China on fundamentally decent footing and I think the US's comparatively good growth since the crisis demonstrates that. And I think if the economy is on decent footing then goods will probably keep finding their way to consumers. Many of the finacial concerns you raise can prevent this, but usually (and hopefully) in the shorter term. If there is an overarching economic question about this it's complexity. The story of the last few decades has been that the world economy has stitched itself more tightly together (which shows up as the increasing financialization you noted earlier). What used to be separate national economies with technological and financial barriers to trade is now one interconnected global economy. Complexity and volatility have accompanied this in ways that are unprecedented. It allows huge amounts of capital to slosh around in beneficial ways (chinese growth) but also destructive ones. The story of the financial crisis was that some new financial asset got created, but the new part was that money from the entire globe sloshed in quickly to grab it up. What might have been a minor bubble in earlier decades became a worldwide crisis because of the complexity and the unpredictability of both the asset itself and the way the global economy entangled it. If bubbles are increasing in frequency or size it's because of this interconnected complexity, which I'm not completely sure we know how to manage. Greece is a sideshow but part of the narrative of interconnectedness. The rest of the world gave them a credit card with the limit a bit too high. Their economy never had the fundamentals to support their spending and it's a bubble in every sense, one that was enabled by the new global economy. So I don't really see an unbalanced world economy overall. I see slower first world growth in the big picture as a balancing force (though agree that Japan's stagnation is hard to explain) and see Chinese growth as being logical and probably sustainable even if it has some bumps in the road (with the main question being why other countries can't get on the same track). So no I don't really have much in the way of counter examples, just different perspective.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:You're surprisingly negative about American economy given how it compares to other rich nations right now, notably Europe. At first I thought this post was unreadable but it paid off in a big way.

|

|

|

|

Arglebargle III posted:At first I thought this post was unreadable but it paid off in a big way. And? War actually serves as an excelent context for highlighting the fundamentals of economics.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Well as a really long aside my economic thinking originates from summers spent playing starcraft while watching the History Channel play endless loops of WWII documentaries. This has to do with economics because the overarching narrative of WWII was supply. It was the economies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union which won the war. lmao. Welp that explains why you poo poo up every goddamn economics thread posted with retarded garbage.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:And? War actually serves as an excelent context for highlighting the fundamentals of economics. It can. History channel documentaries and fuckin' starcraft do not. HTH.

|

|

|

|

Raskolnikov38 posted:It can. History channel documentaries and fuckin' starcraft do not. HTH. Back in the day the history channel did have history. Though to be fair I watched discovery (never great but 10x better than today) and PBS too. Starcraft is a passing reference to the time period, like 1998. What were your thoughts on economics in 1998?

|

|

|

|

Wages of Destruction by Tooze would perhaps give you that insight, a two minutes blurb inbetween war footage about how mass production good, specialized production bad, is not enough to use as a basis for forming any opinion of economics.

|

|

|

|

Here's a neat bulletin from the Bank of England for anyone interested in how money is created. What it boils down to is that banks aren't intermediaries which lend out other peoples deposits. Nor do they "multiply" deposits through the "multiplier effect". When a bank lends money, it simultaneously creates an asset on it's balance sheet (the loan) and a liability (the deposit). Most money is created this way (97% in the UK, slightly lower, I think ~95% in the US). As it turns out, when you have banks creating money for profit, things can get a bit messy! http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/workingpapers/2015/wp529.pdf posted:Economic models that integrate banking with macroeconomics are clearly of the greatest practical relevance at the present time. The currently dominant intermediation of loanable funds (ILF) model views banks as barter institutions that intermediate deposits of pre-existing real loanable funds between depositors and borrowers. The problem with this view is that, in the real world, there are no pre-existing loanable funds, and ILF-type institutions do not exist. Instead, banks create new funds in the act of lending, through matching loan and deposit entries, both in the name of the same customer, on their balance sheets. The financing through money creation (FMC) model reflects this, and therefore views banks as fundamentally monetary institutions. The FMC model also recognises that, in the real world, there is no deposit multiplier mechanism that imposes quantitative constraints on banks’ ability to create money in this fashion. The main constraint is banks’ expectations concerning their profitability and solvency. In this paper, we have developed and studied simple, illustrative models that reflect the FMC function of banks, and compared them to ILF models. Following identical shocks, FMC models predict changes in bank lending that are far larger, happen much faster, and have much larger effects on the real economy than otherwise identical ILF models, while the adjustment process depends much less on changes in lending spreads. As a result, FMC models are more consistent with several aspects of the data, including large jumps in lending and money, procyclical bank leverage, and quantity rationing of credit during downturns.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:You're surprisingly negative about American economy given how it compares to other rich nations right now, notably Europe. I'll be honest, I find this to be a discouraging way for you to start your post because it makes me feel like you completely ignored what I was saying. I think the entire world economy is performing poorly right now. quote:Well the fact that inflation isn't high sort of contrasts with the idea that that there is mounting asset bubble. And setting aside our recent housing based financial crash it's otherwise a bit difficult to link housing with other narratives like quantitative easing because of the amount of special attention housing gets (fannie, freddie, tax credits etc). I don't know what you consider "high inflation" to be but by most standards inflation was not particularly high in the years building up to the 2008 crash (it spiked to about 4% in 2007 but even that is only about a percentage point above the long term US average) nor was it alarmingly high in Japan prior to their crash. Besides, why is it hard to imagine we could simultaneously have near deflation in some parts of the economy (a reflection of low demand and an extremely weak labour movement that cannot press for wage increases) while blowing bubbles in others (thanks to an excess of capital chasing high return investments and very generous government policies toward financial markets)? quote:Well crappy tech startups are a bubble in my opinion but hopefully a minor one and I've always found housing price growth rates to be alarming but with otherwise low inflation it's hard to think we have a terribly large mounting bubble. Quantitative easing is pretty logical policy during times of slack demand and low inflation and it's reasonably straightforward to see that as inflation ticks up it's time to end it. I don't necessarily see cause for concern (qualified by large amounts of uncertainty that acompany any economic prediction). I don't really see how the supposedly central purpose of the market, i.e. "price discovery", can reliably occur during a period of quantitative easing. And quantitative easing really only makes sense as a policy insofar as traditional fiscal policy is politically impossible and traditional monetary policy is ineffective because interest rates are already so low. Again, this all just comes back to my central point: highly unorthodox and opaque policies by the world's largest economies are the only thing holding off another economic collapse, and this has been true since 2008. The fact you don't see this as a cause for greater alarm about the stability of the global economic system is curious to me. quote:Well I'll say that I don't feel confident that I understand the inner workers of the Chinese government and it's clear that all of China's growth hangs off their decisions. But in the big picture China isn't greece. Their growth has been the result of them building things and the result of them putting people to work in increasingly skilled and productive ways. That is sustainable growth and I tend to think that even if they have a crash they'll be able to weather it. Japan - a country with a lot more political stability to begin with - also massively ramped up their productive capacity and probably had the most sophisticated and automated factories in the world by the end of the 1980s. This did not save them from two lost decades and counting of economic stagnation. Under a different economic system enhanced productive capacity would indeed mean greater wealth but under capitalism that is absolutely not guaranteed. quote:Well that's not a terribly interesting thought because everything benefits someone even if it's the morgue in a plauge. It's interesting because a bubble is caused by humans whereas a plauge is a natural event. The US bubble, in particular, was triggered by the behaviour of people and firms who knew that their social and political power would insulate them from the potential ramifications of their actions. quote:The inconcistent part would be to imply that the bubble get any credit for the growth. There is a suble difference between that and noting a correlation. The economy doesn't benefit in the long term by employing 100's of skilled workers to develop pets.com before throwing it in the toilet. What I'm saying is that there are no clear examples of fast growing large economies that didn't experience major bubbles and/or rely heavily on exporting to bubble economies. This was my original question and so far I don't feel you've provided any examples. quote:Well as a really long aside my economic thinking originates from summers spent playing starcraft while watching the History Channel play endless loops of WWII documentaries. This has to do with economics because the overarching narrative of WWII was supply. It was the economies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union which won the war. Honestly I find these statements a bit jumbled. I do not see how anything you're saying here relates to my comments about the financialization of major economies post-1970s. You'll have to clarify why you think this addresses anything we're talking about. quote:I can't see big picture economic stuff from quite the same perspective here. I see both the U.S. and China on fundamentally decent footing and I think the US's comparatively good growth since the crisis demonstrates that. And I think if the economy is on decent footing then goods will probably keep finding their way to consumers. Many of the finacial concerns you raise can prevent this, but usually (and hopefully) in the shorter term. My suggestion to you is that what happened to Japan was an early warning of what is happening to most, if not all, advanced economies. In fact the Japanese story of a rapidly inflating property bubble followed by a very anaemic recovery is very reminiscent of what happened to the US and what may be happening to China right now.

|

|

|

|

Effectronica posted:Sure, sure, we can reasonably say that once you reach the point of drag on employment, there's a sudden crash such that it's better to have 35 million people on the edge of desperation than not. This is certainly far more reasonable than suggesting a still-inadequate $15/hr minimum wage would have marginal effect on employment. Indeed, one might say infinitely so, if that weren't taken up by appealing to authority's halcyon place at the apex of reasonable. I think kreuger might suspect that a $15 minimum wage would make the poor better off, but doesn't support a $15 national minimum wage for a few reasons. 1). He's an empiricist and feels less comfortable than you in making faith-based predictions about economic policy. 2). He wants to prove with research that a higher minimum wage would help the poor, and doesn't want a national $15 wage because that would destroy the best natural experiments; contiguous state and city borders with a minimum wage differential. 3). He knows there's a lot of noise in economic data, and fears that factors exogenous to the minimum wage could cause an economic downturn that would then be attributed to the minimum wage. JeffersonClay fucked around with this message at 16:02 on Oct 12, 2015 |

|

|

|

JeffersonClay posted:I think kreuger might suspect that a $15 minimum wage would make the poor better off, but doesn't support a $15 national minimum wage for a few reasons. Basically he feels that a $15 national wage is untested territory, especially in states with significantly different costs of living. Ultimately, the solution would probably be having a $15 minimum approached over a longer time span and then maybe giving states the opportunity to approach it slower than others.

|

|

|

|

On the topic of the $15 minimum wage it looks like it's proceeding in Sea Tac following a court challenge.PBS posted:TRANSCRIPT Meanwhile in New York a panel appointed by the governor just recommended the implementation of a $15 minimum wage, phased in faster in New York City but eventually covering the entire state. I will point out again that this is not really a technical policy - or at least not exclusively a technical policy - but rather a question of whether struggling workers can actually enforce their political interests onto a system that mostly excludes them.

|

|

|

|

Helsing posted:Meanwhile in New York a panel appointed by the governor just recommended the implementation of a $15 minimum wage, phased in faster in New York City but eventually covering the entire state. It in some ways it seems to ultimately end up too much of a political challenge to ignore. That said, politicians won't actively try to fix it beyond it reaches a point where the public will actively vote against them. That said, even if some of the progress that is being made, if you look at the rising cost of housing in many cities, it is often rising far higher than even optimistic increases in the minimum wage. In Portland, rent prices are rising 15-20% a year and ultimately the question is can you find a minimum wage to take that into account. In many ways it delved deeper into the problem where, while a national/state minimum wage needs to be far higher there are limits to its utility especially when you get to severe but localized cost of living issues. San Francisco for example raised its minimum wage to $15 a hour, but looking at the often sky-high amounts of rent being charged, it may have to be even higher or simply another solution needs to be found.

|

|

|

|

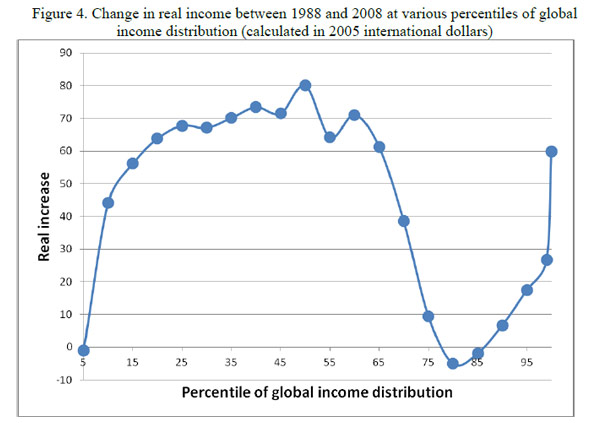

Helsing posted:I'll be honest, I find this to be a discouraging way for you to start your post because it makes me feel like you completely ignored what I was saying. I think the entire world economy is performing poorly right now. Umm, why? We're probably coming off the best 2 decades or so in worldwide economic history with high growth and probably no increase in inequality. That means on average everyone has benefitted (and the notable losers are ~80th percentile). So what do you want? http://www.krusekronicle.com/kruse_kronicle/2008/12/200208-60-growth-in-world-percapita-real-gdp-.html#.Vh2aZBNViko  https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/10/27/workers-of-the-world-cannot-unite-conclusive-evidence/ quote:I don't know what you consider "high inflation" to be but by most standards inflation was not particularly high in the years building up to the 2008 crash (it spiked to about 4% in 2007 but even that is only about a percentage point above the long term US average) nor was it alarmingly high in Japan prior to their crash. Well we can but it's less likely with inflation hovering near zero and less likely to have a large impact if it does pop. quote:I don't really see how the supposedly central purpose of the market, i.e. "price discovery", can reliably occur during a period of quantitative easing. And quantitative easing really only makes sense as a policy insofar as traditional fiscal policy is politically impossible and traditional monetary policy is ineffective because interest rates are already so low. I don't really agree. Generally increasing the money supply increases demand for everything which doesn't impact the most important aspect of prices - relative value. The exact values of QE are public and the impact of printing money isn't exactly a mystery and consistent with Keynesian policy. Point to a time period in the last two centuries where capitalism wasn't evolving or where there weren't a significant segment of the population fearful of recent changes and worried about the future. Part of the point of my rant about economic fundamentals was to express why I think it's useful to temper concerns over some of the financial concerns you're raising. They're not as important in the big picture as they seem (and almost impossible to understand even if they are). quote:Japan - a country with a lot more political stability to begin with - also massively ramped up their productive capacity and probably had the most sophisticated and automated factories in the world by the end of the 1980s. This did not save them from two lost decades and counting of economic stagnation. Well besides noting that Japan is near the top of the GDP per capita list and therefore I'm not terribly concerned about them I'll say that they are a really interesting exception. Clearly there are no fundamental economic problems preventing them from growing so the problem is financial or political. Beyond that I don't know what to say except that yes, it's possible that any country could stop growing like Japan. I just don't see why I should think that will happen. For example China is decades away from that type of GDP per capita. If there is a hard upper limit on GDP growth then that's probably a good thing for long term inequality. quote:Under a different economic system enhanced productive capacity would indeed mean greater wealth but under capitalism that is absolutely not guaranteed. If you say so... quote:It's interesting because a bubble is caused by humans whereas a plauge is a natural event. The US bubble, in particular, was triggered by the behaviour of people and firms who knew that their social and political power would insulate them from the potential ramifications of their actions. I'm still not convinced you have a coherent definition for bubble. The countries sitting at the top of the GDP per capita list that have almost all been there for decades aren't bubbles. They have experienced bubbles but their economies aren't explained by bubbles. I already noted how China has grown through U.S. recessions and overall, developing economies were far less affected by the crisis and bounced back to pre-crisis growth quickly. The mechanics of trade and comparative advantage that are the basic drivers of export growth continue to work even when the rich countries stall out (which is basically what's happened in the last 7 years). China continued growing through the crisis and so did India:  quote:Honestly I find these statements a bit jumbled. I do not see how anything you're saying here relates to my comments about the financialization of major economies post-1970s. You'll have to clarify why you think this addresses anything we're talking about. The idea that Japan represents the future of the first world is possible. I just see no reason to think it is at this point. But comparing Japan to China makes no sense given the massive wealth disparity between them. China hasn't hit the middle income trap, let alone the upper income trap Japan occupies. Even if the entire first world stagnates it's another leap to decide that 1) that matters much to the rest of the world or 2) is a bad thing in the big picture (they've already been growing slower for decades). asdf32 fucked around with this message at 02:15 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

Bryter posted:Here's a neat bulletin from the Bank of England for anyone interested in how money is created. Although often terribly presented, I don't think the "multiply" model is worth throwing out as it captures certain mechanics and history of banking. Fractional reserve banking actually works on goods too. Imagine an economy where everything is based on grain. One older family may have saved a big pile of grain and one younger family may have almost none. If the older savers put their grain in a bank then the younger family can borrow it and eat it now. The younger family really has the grain and the older family behaves like they have the grain. Although no physical grain has been created there is a perception within the economy that the grain supply has increased. Among other places, fractional reserve banking evolved exactly like this except with scripts for gold. The thing with money is that it's virtual, so we accept that the increased perception of money really is an increase in the money supply. In general the basic model above is a pretty good example of the power and limitations of finance. It can be extremely powerful at making better use of resources that are available but it generally can't be credited with the creation of those resources itself. This paper seems to be combining this with some aspects of modern mechanics to make another leap in a model for systemic banking behavior. Wikipedia posted:In the past, savers looking to keep their coins and valuables in safekeeping depositories deposited gold and silver at goldsmiths, receiving in exchange a note for their deposit (see Bank of Amsterdam). These notes gained acceptance as a medium of exchange for commercial transactions and thus became an early form of circulating paper money.[6] As the notes were used directly in trade, the goldsmiths observed that people would not usually redeem all their notes at the same time, and they saw the opportunity to invest their coin reserves in interest-bearing loans and bills. This generated income for the goldsmiths but left them with more notes on issue than reserves with which to pay them. A process was started that altered the role of the goldsmiths from passive guardians of bullion, charging fees for safe storage, to interest-paying and interest-earning banks. Thus fractional-reserve banking was born. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 02:06 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

JeffersonClay posted:I think kreuger might suspect that a $15 minimum wage would make the poor better off, but doesn't support a $15 national minimum wage for a few reasons. You should learn what words like "empirical" mean so you don't end up saying silly things like "We can't implement this policy in the real world until we have data from its implementation in the real world." If economists engage in this kind of sloppy thinking regularly, that explains a lot. Unfortunately, you didn't respond to anything I actually said, so there's nothing else to say without repeating myself, which looks to be pretty pointless.

|

|

|

|

|

Effectronica posted:You should learn what words like "empirical" mean so you don't end up saying silly things like "We can't implement this policy in the real world until we have data from its implementation in the real world." If economists engage in this kind of sloppy thinking regularly, that explains a lot. Unfortunately, you didn't respond to anything I actually said, so there's nothing else to say without repeating myself, which looks to be pretty pointless. You completely miss the point there. Doing a nationwide $15/hour minimum wage would make empirical study of that wage level's effects impossible, as it would remove any control group for your study. Any argument about if it was helpful or hurtful, if it was a drag on employment or not, would come down to arguing counterfactuals. The current path, where some areas are implementing it and some aren't, gives you real data that can be studied and compared between areas where it was implemented and where it wasn't.

|

|

|

|

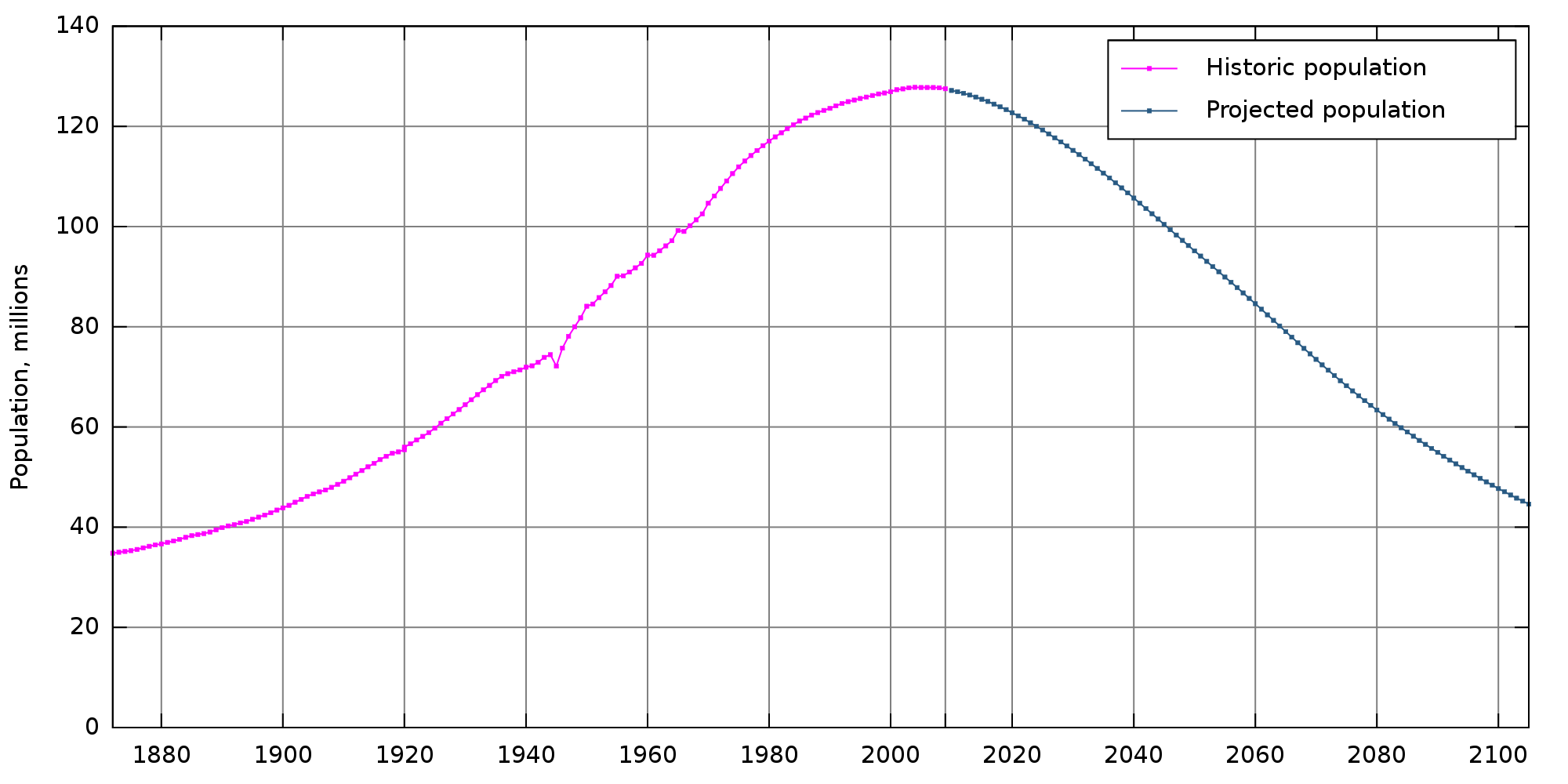

asdf32 posted:Well besides noting that Japan is near the top of the GDP per capita list and therefore I'm not terribly concerned about them I'll say that they are a really interesting exception. Clearly there are no fundamental economic problems preventing them from growing so the problem is financial or political. Beyond that I don't know what to say except that yes, it's possible that any country could stop growing like Japan. I just don't see why I should think that will happen. For example China is decades away from that type of GDP per capita. If there is a hard upper limit on GDP growth then that's probably a good thing for long term inequality. pictured: no fundamental economic problem preventing growth:  The idea is that long-term demographics for all countries not big enough and wealthy enough to attract human capital from abroad (basically everyone not named the US and possibly the UK) will kill off growth. And also, I'm sort of bemused by the idea that financial or political problems somehow aren't 'fundamental economic problems'? They have the same effect on the economy, why would they not be as serious? Take India or Latin America, for example. Their failure to grow could probably be described as political, but they're still not growing at the end of the day More generally though you still haven't really addressed the fact that almost all of the growth in the last few decades has been in China, whose export strategy is not generally repeatable by the rest of the developing world, and even with that export crutch Chinese growth still seems to be dying icantfindaname fucked around with this message at 16:03 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:pictured: no fundamental economic problem preventing growth: It doesn't help that Japan has more or less maximized the utility of monetary and fiscal intervention, and broader social progress "the third arrow" has been quite limited. While Japan has been cited as especially xenophobic, they aren't the only country out there with similar urges either.

|

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:pictured: no fundamental economic problem preventing growth: Like, capital demands growth, and you could theoretically deliver overall growth by forced breeding, wage slavery, and mandatory consumption, but I think we can agree that would be a pretty bad thing even if it delivered results. Much like under mercantilism you could secure ongoing growth by a process of stealing other people's poo poo. Current thinking demands a constantly increasing population to deliver constantly increasing growth, but that must logically have a limit somewhere, and if increasing the population means that there are more people who have less then it's not what I'd call a good system.

|

|

|

|

Guavanaut posted:Isn't it more important how much each person has rather than how much growth each country has? Much of it is about demographics, specifically you need young people to consume (providing a domestic market) and hopefully work (feeding tax revenue back into the system). Ultimately, they need some time of income for this to work and yes, while growth is only part of the equation, you do want a expanding economy. (Sidenote: MMT falls apart when you get to issue of trade balances and exterior purchasing. Sadly enough Venezuela kind of killed MMT.) Basically, much of it is balancing act between income growth, economic growth, stable demographics, and inflation. The Asian tigers for the most part were able to keep their system moving forward through stable population growth and a booming export market while actual income growth usually lagged and inflation often was quite high. However, this in part required a political alliance that wasn't necessarily easily replicated. India on the other hand had long been blasted for its "Hindu level of growth" during the Cold War, usually blamed on "red tape" but usually its non-aligned status and ambiguous trade relationship with both Comecon and Western countries is ignored. Ardennes fucked around with this message at 14:58 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:pictured: no fundamental economic problem preventing growth: Japan's demographic crisis has definitely hurt its chances of recovery, but it doesn't explain the stagnation in the 1990s-early 2000s. I don't know what the explanation is, but I'm guessing it involves some political mistakes as well as economic fundamentals (more competition from Korea and China, for example).

|

|

|

|

Guy DeBorgore posted:Japan's demographic crisis has definitely hurt its chances of recovery, but it doesn't explain the stagnation in the 1990s-early 2000s. I don't know what the explanation is, but I'm guessing it involves some political mistakes as well as economic fundamentals (more competition from Korea and China, for example). Japan hosed up its response to the early 90s bubble, IIRC. Even then it sort of recovered and had decent (2%-ish) growth for a while from the late 90s to 2008. The demographic impact is mostly being felt in its failure to recover from 2008 icantfindaname fucked around with this message at 18:00 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Although often terribly presented, I don't think the "multiply" model is worth throwing out as it captures certain mechanics and history of banking. It captures mechanics, but the wrong way around. The Federal Reserve sure think it's worth throwing out: http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/201041/201041pap.pdf quote:We conclude that the textbook treatment of money in the transmission mechanism can be rejected. Specifically, our results indicate that bank loan supply does not respond to changes in monetary policy through a bank lending channel, no matter how we group the banks. And the BoE working paper above is particularly hard on it: quote:In undergraduate textbooks one also finds the older deposit multiplier (DM) model of banking, but this has not featured at all in the recent academic literature. We will nevertheless discuss it later in this paper, because of its enduring influence on popular understandings of banking.

|

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:Japan hosed up its response to the early 90s bubble, IIRC. Even then it sort of recovered and had decent (2%-ish) growth for a while from the late 90s to 2008. The demographic impact is mostly being felt in its failure to recover from 2008 The demographic impact if anything may have started in the late 90s/early 2000s since Japanese population growth really started to decline in the early 80s. That said, quite simply the realities for Japanese growth simply couldn't meet the (unacceptable) expectations of it. By the early 1980s it had maximized its export policy and its domestic infrastructure policy was getting progressively less returns. They swelled one of the biggest housing bubbles in history to counter it and flooded corporations with cheap money, and only continued to flood they after the property market collapsed. If anything they did almost everything Keynesians would expect of them, even pressing that to its limits and yet it still wasn't enough. One other issue that wasn't been mentioned is simply wages, and while Japan always has had a very protectionist trade policy, but it also been affected by globalization. If anything the Japan car companies (ironically enough) have moved some manufacturing back to the US because of cheap labor, not to mention China and the rest of Asia. They maximized their returns from trade, gave corporations and banks every yen they could want, and built every piece of infrastructure they could think of it and it still wasn't enough. As for their future, I guess can say it would still take quite a while for them to fully collapse.

|

|

|

|

Effectronica posted:You should learn what words like "empirical" mean so you don't end up saying silly things like "We can't implement this policy in the real world until we have data from its implementation in the real world." If economists engage in this kind of sloppy thinking regularly, that explains a lot. Unfortunately, you didn't respond to anything I actually said, so there's nothing else to say without repeating myself, which looks to be pretty pointless. So far in this thread you've described the conclusions of experts as appeals to authority and empiricism as sloppy thinking. What, then, informs your understanding of economics? Do you derive it from first principles?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 18, 2024 10:38 |

JeffersonClay posted:So far in this thread you've described the conclusions of experts as appeals to authority and empiricism as sloppy thinking. What, then, informs your understanding of economics? Do you derive it from first principles? I said that saying "this guy said it and he's smart" is an appeal to authority. I am right in that statement. I said that empiricism is concluding based on observations, and I am right in that statement. I said that confusing empiricism with other forms of reasoning is sloppy thinking, and I am right in that statement. The simple fact of the matter is that, if I take you as knowledgeable about economics, economics is nonsense. If I take you as an idiot, you're not worth talking to. If I take you as a monomaniac, discussion requires some prerequisites. Which of the three is true, JeffersonClay?

|

|

|

|