|

Helsing posted:On the topic of economic growth, can anybody here think of a major country in the last few decades who has developed without relying on either massive government spending, an asset bubble, or exports to a country with at least one of the former two traits. China has sustained growth through periods of US and western recession. And at this stage the first world is diminishing in terms of its share of world consumption. So I don't think bubbles or "juicing" have played a necesary role in 3rd world export growth. I also don't see why you'd associate bubbles with [long term] growth. They're inneficient and potentially destructive. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 22:27 on Sep 29, 2015 |

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 30, 2024 23:58 |

|

Jagchosis posted:Chinese growth was largely built on exports to the West (notable exception being Chongqing, which grew through catering to domestic demand for goods) and when the Western economy collapsed in 2008, China shored up demand through massive government spending. So it fails like every point of the question he's asking. First, there are other recessions such as 2001. And other examples of sustained export led growth of say the other Asian tigers which spanned a range of global financial conditions. Second, I'm not yet clear what Helsing's definitions for say "juicing" is.

|

|

|

|

Sorry I didn't help you more with this: That's a perfect example of how and why Chinese growth doesn't depend on U.S. bubbles steinrokkan posted:Chinese economic growth is 100% thanks to government spending and government agencies juicing their budgets as much as possible. Those papers are discussing events in 2009 which at best have little to do with multiple decades of prior Chinese growth. For future reference in this thread:

asdf32 fucked around with this message at 00:26 on Sep 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

Zohar posted:Yeah a research paper written in 2006 sure is discussing events in 2009. That bubbles don't explain most growth in the last few decades and "juicing" needs a definition before we probably conclude the same thing about it.

|

|

|

|

Jagchosis posted:By "juicing" he means fiscal (stimulus) and monetary (e.g. QE) expansion of demand and money supply are you that thick Ok so you get that we can't credit countercyclical stimulus with growth right? And that if we broaden the term stimulus to include run-of-the-mill fiscal/monetary it probably doesn't deserve the term "juicing"? That's why if there's any substance here we need a better definition. The phrase "juicing" evokes something like cheating. If we came up with a new fiscal policy that reliably created sustainable growth it wouldn't be cheating. It would be the best fiscal policy and we'd use it all the time and we wouldn't call it "juicing". Periodic stimulus evokes the phrase juicing because it encompases policy which only works in short doses by its nature (like QE).

|

|

|

|

CommieGIR posted:Juicing is a different way of saying "Cooking the books" I don't think that's what Helsing meant. And while we can debate the numbers, there is no question China has grown "a lot".

|

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:I mean more graduating from middle income to high income, which is what Latin America failed to do and has basically never been done outside of edge cases like South Korea, which is still at the poor end of developed countries The other Asian tigers, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and then Japan before that are the primary examples. The best conclusion is that it comes down to decent government which is able to improve institutions as the economy develops. With "bad government" (very hard to define) you stall like Argentina (which was unstable and made some huge mistakes). asdf32 fucked around with this message at 12:51 on Sep 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

Veskit posted:Can you be more specific with your statement? Draw correlation to what you're saying and talk about what caused it? Provide information or at least "talk in theory"? Explain what parts are missing things like that. I'm not sure what you're asking for but we're pretty far from the topic of the thread. Those are a list of countries which have succeeded at developing. But development economics is far larger in scope than fiscal or monetary policy. Both play a role behind the scenes but are actually subordinate to the overall political/economic environment (I.E trade policy, regulations, stability, rule of law etc).

|

|

|

|

Veskit posted:Explain how Agentina's "bad government" dictates fiscal policy and how it is crumbling their economy. Or come up with something more imaginative. If you bring up trade policy then that's always interchanged with monetary policy. Regulations are often fiscal policy driven, stability is can be about collecting. Do something. I don't have a clue what many of the answers are except some of the bigger picture observations of the Asian tigers or the first world before them. The point that you should take at the moment is that it's not smart to try and lump everything under fiscal or monetary policy. They're just a subset of overall economic policy and not the most important. It's fine to talk about them. But you can't expect the major developmental questions of our time to be phrased in terms of them alone. Which is what it seems you're askin me to do.

|

|

|

|

Mr Interweb posted:Has there ever been any situation where high interest rates have led to job growth? The intention is to stabilize the economy to prevent a future bust. That's the main benefit. Job growth isn't really it.

|

|

|

|

icantfindaname posted:Japan shouldn't really be on that list, it started industrializing in the 1880s. You might as well put Germany on there too. Japan is on the list because Japan industrialized without benefiting from cultural or geographic proximity with western european first world countries. The 1880's is almost a century later than some of the first industrial states. The point is that the middle income trap is only a trap in modern times given that dozens of now first world states got through, many of them with no real problem. The question of the trap is whether built-in economic advantages now exist that are holding back other states or not. I think the asian tigers are pretty powerful examples that significant economic barriers probably don't exist. Personally, like I said, I think the main barriers are political and still poorly understood.

|

|

|

|

tekz posted:Can you go into more detail about this? I was under the impression that it was protectionism, and pretty heavy-handed protectionism at that, which allowed places like Taiwan, Korea and Japan to get to where they did. They did but protection isn't a binary and import substitution policy which broadly speaking was practiced in Latin America is completely different than the export driven policy of the Asian Tigers. Import substitution is true protection oriented around building internal industries and protecting them from global competition. The export driven policy of the Asian Tigers subsidized internal industries but then then forced them up against competitors in the global market (think Hyundai). One take from wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Import_substitution_industrialization posted:Given import substitution's dependence upon its developed and isolated markets within Latin America, it relied upon the growth of a market that was limited in size. In most cases, the lack of experience in manufacturing, plus lack of competition, reduced innovation and efficiency, which restrained the quality of Latin American produced goods, while protectionist policies kept prices high.[14] In addition, power concentrated in the hands of a few decreased the incentive for entrepreneurial development.

|

|

|

|

tekz posted:Didn't the chaebols have a stranglehold on internal markets for a long enough while to be considered to be practicing 'import substitution'? At what point were they exposed to global competition? In the export market. They very well may have remained protected at home but that doesn't help Hyundai sell Excels in the U.S. The domestic market was tiny and their growth was fueled by exports. And again, besides increasing trade in general this encouraged continued improvements because while the government may have been happy to subsidize it had every reason to want greater return and that meant industry needed to compete on the global market.

|

|

|

|

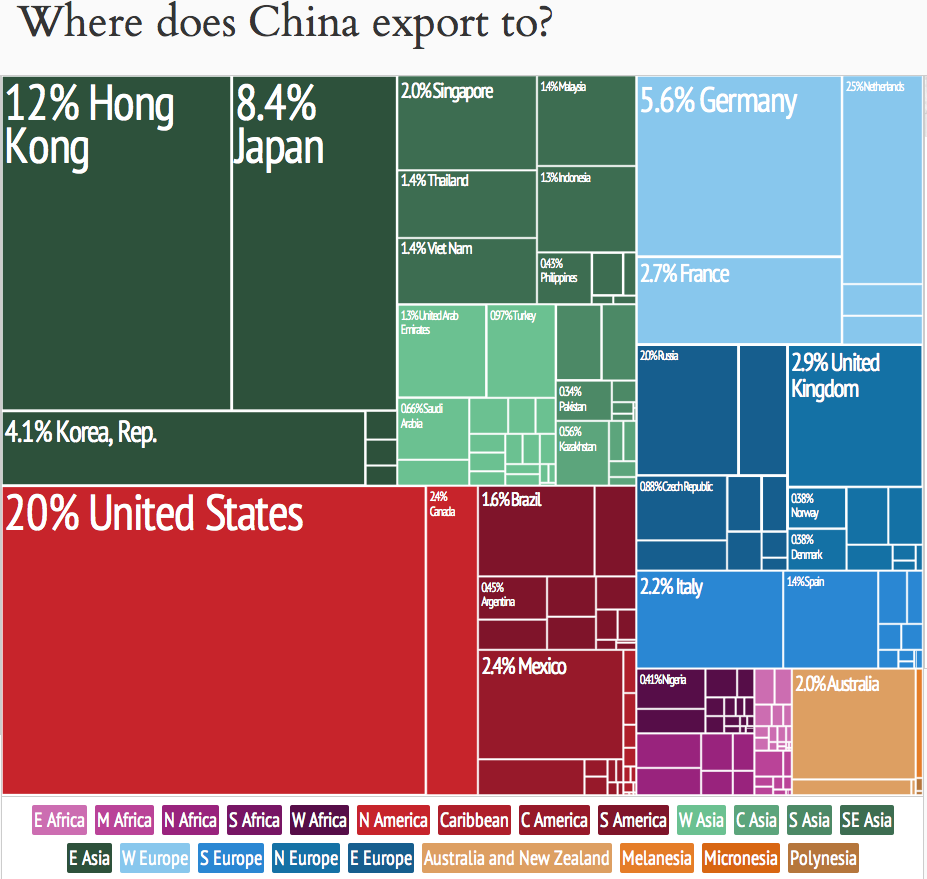

Helsing posted:This thread kind of dropped of my radar so I didn't realize anybody had responded to my posts. Apologies this is coming in late. I don't know why you think U.S. aggregate trade surplus is relevant to China which cares about what the U.S. is buying from them. I want to point out a few things. First, the U.S. isn't as large a percentage of Chinese trade as you may thin. Looking at the chart below you see large squares for other net exporters like Japan and Germany. On the whole, China exports more to the E.U. than to the U.S. and the E.U. is itself a net exporter.   quote:Without the United States acting as the buyer-of-last resort I'm not sure how successful various export oriented economies would have been. In a sense the US economy has been stimulating the rest of the global economy with its large trade deficit which is not necessarily the most balanced or desirable path for global growth. Not true given that the U.S. is only 20% of China's exports and I don't know what you're trying to capture with "buyer of last resort". The U.S. isn't deliberately doing any favors by buying Chinese stuff. I'll assume you're probably implying that U.S. trade deficits aren't sustainable. I don't think that's true in the short or medium term (because of the unique place the dollar has in the world economy which holds up its value). But it doesn't really matter. quote:Well then answer my original question: "If we imagine a world where China and the US aren't juicing their economies and buying up so much of what the rest of the world sells then what might the world economy look like right now?" I don't think juicing is a thing and I don't think there is anything that's going to bring an end to high levels of Chinese trade. What I take you to be implying is that Chinese growth isn't sustainable or isn't more widely applicable. I disagree. At the most basic level trade driven growth is about comparative advantage. It's about trading low skill labor for volumes of higher tech capital. It's not about finance or best explained in terms of finance. As long wage differentials exist there is motivation for rich countries to outsource labor in a way that induces trade. This is fundamentally sustainable and works under a wide range of specific conditions in terms of who the buyers and sellers are, what the specific surpluses are etc. quote:Around the middle of the 1970s economic growth in the developed areas of the world slowed dramatically, and the postwar Bretton Woods system broke down. One of the responses that the share of GDP going toward financial activities began to increase significantly. Since this process of 'financialization' began some forty years ago the economy has behaved differently than it did in the past, with growth tending to produce unstable bubbles that inflate and inflate until they collapse and trigger a major crisis. It's not internally consistent to correctly categorize bubbles as destructive yet credit them with growth. Bubbles are market failures. They represent misallocations of capital which only look beneficial while they're happening and then are clearly destructive when they pop. They don't benefit anyone in the long run. You're correct to correlate growth and bubbles because that's what history demonstrates. Bubbles are helped by the dynamism that often accompanies growth. But bubbles are only parasitic in that process. I don't know what your question is intending to mean. The U.S. is world's largest source of research and development (notably technology and drugs) and China is the world's largest manufacturer. That's what they mean to the world economy and these are desirable things. The U.S. is slowly receding in terms of its share of the world economy and China is growing. There is nothing fundamentally unsustainable about either thing.

|

|

|

|

Helsing posted:The fact that one dollar of exports out of every five is going to the United States is a massive figure. Obviously China has other important trade partners but the numbers you just provided seem to illustrate how crucial the Chinese-US trade relationship is for Chinese growth and development. You're surprisingly negative about American economy given how it compares to other rich nations right now, notably Europe. Well the fact that inflation isn't high sort of contrasts with the idea that that there is mounting asset bubble. And setting aside our recent housing based financial crash it's otherwise a bit difficult to link housing with other narratives like quantitative easing because of the amount of special attention housing gets (fannie, freddie, tax credits etc). quote:I'm obviously not some kind of free market purist who thinks there's some 'true' price for assets that quantitative easing is distorting but what this amounts to is the US Fed taking aggressive and unorthodox measures to prop up an otherwise very weak economy. So I suspect what we'll discover once quantitative easing tapers off is that many US assets are currently priced at levels that will no longer make sense in the absence of quantitative easing. Indeed we may discover that once again the US economy has gone into bubble territory (does anyone think all those tech companies that never turn a profit are being valued accurately right now?). Well crappy tech startups are a bubble in my opinion but hopefully a minor one and I've always found housing price growth rates to be alarming but with otherwise low inflation it's hard to think we have a terribly large mounting bubble. Quantitative easing is pretty logical policy during times of slack demand and low inflation and it's reasonably straightforward to see that as inflation ticks up it's time to end it. I don't necessarily see cause for concern (qualified by large amounts of uncertainty that acompany any economic prediction). quote:In China we have even less sense of what happens behind closed doors but certainly there are all kinds of implicit guarantees, backdoor deals and outright corruption underlying Chinese growth. China has shitloads of domestic debt piling up and it's not clear how much of that debt was extended for financial reasons vs. how much of it was essentially a political transfer of wealth. Then on top of that we have the government's absolutely enormous post-2008 stimulus plan which involved really massive spending on investments to maintain demand for Chinese products after the western economies slowed down. Well I'll say that I don't feel confident that I understand the inner workers of the Chinese government and it's clear that all of China's growth hangs off their decisions. But in the big picture China isn't greece. Their growth has been the result of them building things and the result of them putting people to work in increasingly skilled and productive ways. That is sustainable growth and I tend to think that even if they have a crash they'll be able to weather it. quote:I'm not saying there's something in particular that is wrong with export-oriented industrialization strategies - I think that under the right conditions such a strategy can obviously be successful in building a developed economy. Rather my comment is on the unbalanced and precarious nature of global growth in general. Well that's not a terribly interesting thought because everything benefits someone even if it's the morgue in a plauge. The inconcistent part would be to imply that the bubble get any credit for the growth. There is a suble difference between that and noting a correlation. The economy doesn't benefit in the long term by employing 100's of skilled workers to develop pets.com before throwing it in the toilet. quote:This goes back to my previous comment about the move toward financialization since the 1970s. As the financial industry has replaced manufacturing as the central motor of the economy and as debt has started to replace wages as the main driver of consumer demand we've seemingly entered a situation where no economy can grow for a sustained period of time without inflating huge asset or commodity bubbles. This was perhaps less true during the Bretton Woods era when strict capital controls and strong regulatory national governments behaved very differently but in the post-70s world I can't think of any examples of countries that grew at a large and sustained rate without falling prey to very serious bubbles. Can you? Well as a really long aside my economic thinking originates from summers spent playing starcraft while watching the History Channel play endless loops of WWII documentaries. This has to do with economics because the overarching narrative of WWII was supply. It was the economies of the U.S. and the Soviet Union which won the war. War time distils economics down to it's most base components. It takes capital and labor to produce a tank and it takes capital and labor to produce a plane. No amount of financial shenanigans in the world can substitute for the massive quantities of steel and 1000's of skilled man-years that it takes to build a ship. When a wartime nation's currency plummets in value due to inflation it's the result of the economy running out of it's core ingredients, not the cause of it. The sort of layman's understanding of financial demand obfuscates this in multiple ways. First it simplifies the incredible complexity inherent to a large economy. Consider the number of people sitting in planning offices coordinating the movement of supplies like toothpaste, chocolate bars, 100's of types of ammunition and 1000's of spare parts around the globe during the war. When you hand a dollar to a cashier all that complexity sits behind your demand for the good. But it complicates the basics with quickly impenetrable layers of mathematical complexity. I can't see big picture economic stuff from quite the same perspective here. I see both the U.S. and China on fundamentally decent footing and I think the US's comparatively good growth since the crisis demonstrates that. And I think if the economy is on decent footing then goods will probably keep finding their way to consumers. Many of the finacial concerns you raise can prevent this, but usually (and hopefully) in the shorter term. If there is an overarching economic question about this it's complexity. The story of the last few decades has been that the world economy has stitched itself more tightly together (which shows up as the increasing financialization you noted earlier). What used to be separate national economies with technological and financial barriers to trade is now one interconnected global economy. Complexity and volatility have accompanied this in ways that are unprecedented. It allows huge amounts of capital to slosh around in beneficial ways (chinese growth) but also destructive ones. The story of the financial crisis was that some new financial asset got created, but the new part was that money from the entire globe sloshed in quickly to grab it up. What might have been a minor bubble in earlier decades became a worldwide crisis because of the complexity and the unpredictability of both the asset itself and the way the global economy entangled it. If bubbles are increasing in frequency or size it's because of this interconnected complexity, which I'm not completely sure we know how to manage. Greece is a sideshow but part of the narrative of interconnectedness. The rest of the world gave them a credit card with the limit a bit too high. Their economy never had the fundamentals to support their spending and it's a bubble in every sense, one that was enabled by the new global economy. So I don't really see an unbalanced world economy overall. I see slower first world growth in the big picture as a balancing force (though agree that Japan's stagnation is hard to explain) and see Chinese growth as being logical and probably sustainable even if it has some bumps in the road (with the main question being why other countries can't get on the same track). So no I don't really have much in the way of counter examples, just different perspective.

|

|

|

|

Arglebargle III posted:At first I thought this post was unreadable but it paid off in a big way. And? War actually serves as an excelent context for highlighting the fundamentals of economics.

|

|

|

|

Raskolnikov38 posted:It can. History channel documentaries and fuckin' starcraft do not. HTH. Back in the day the history channel did have history. Though to be fair I watched discovery (never great but 10x better than today) and PBS too. Starcraft is a passing reference to the time period, like 1998. What were your thoughts on economics in 1998?

|

|

|

|

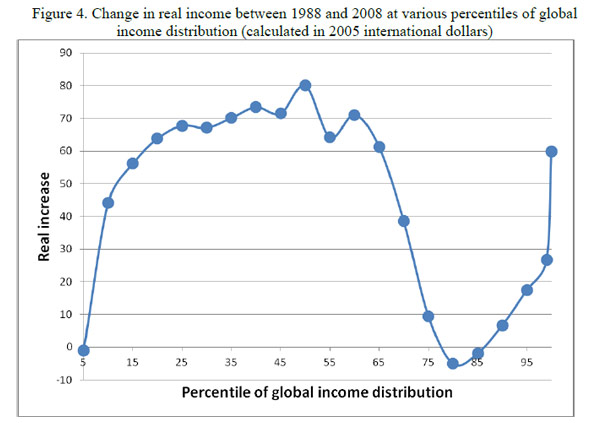

Helsing posted:I'll be honest, I find this to be a discouraging way for you to start your post because it makes me feel like you completely ignored what I was saying. I think the entire world economy is performing poorly right now. Umm, why? We're probably coming off the best 2 decades or so in worldwide economic history with high growth and probably no increase in inequality. That means on average everyone has benefitted (and the notable losers are ~80th percentile). So what do you want? http://www.krusekronicle.com/kruse_kronicle/2008/12/200208-60-growth-in-world-percapita-real-gdp-.html#.Vh2aZBNViko  https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2013/10/27/workers-of-the-world-cannot-unite-conclusive-evidence/ quote:I don't know what you consider "high inflation" to be but by most standards inflation was not particularly high in the years building up to the 2008 crash (it spiked to about 4% in 2007 but even that is only about a percentage point above the long term US average) nor was it alarmingly high in Japan prior to their crash. Well we can but it's less likely with inflation hovering near zero and less likely to have a large impact if it does pop. quote:I don't really see how the supposedly central purpose of the market, i.e. "price discovery", can reliably occur during a period of quantitative easing. And quantitative easing really only makes sense as a policy insofar as traditional fiscal policy is politically impossible and traditional monetary policy is ineffective because interest rates are already so low. I don't really agree. Generally increasing the money supply increases demand for everything which doesn't impact the most important aspect of prices - relative value. The exact values of QE are public and the impact of printing money isn't exactly a mystery and consistent with Keynesian policy. Point to a time period in the last two centuries where capitalism wasn't evolving or where there weren't a significant segment of the population fearful of recent changes and worried about the future. Part of the point of my rant about economic fundamentals was to express why I think it's useful to temper concerns over some of the financial concerns you're raising. They're not as important in the big picture as they seem (and almost impossible to understand even if they are). quote:Japan - a country with a lot more political stability to begin with - also massively ramped up their productive capacity and probably had the most sophisticated and automated factories in the world by the end of the 1980s. This did not save them from two lost decades and counting of economic stagnation. Well besides noting that Japan is near the top of the GDP per capita list and therefore I'm not terribly concerned about them I'll say that they are a really interesting exception. Clearly there are no fundamental economic problems preventing them from growing so the problem is financial or political. Beyond that I don't know what to say except that yes, it's possible that any country could stop growing like Japan. I just don't see why I should think that will happen. For example China is decades away from that type of GDP per capita. If there is a hard upper limit on GDP growth then that's probably a good thing for long term inequality. quote:Under a different economic system enhanced productive capacity would indeed mean greater wealth but under capitalism that is absolutely not guaranteed. If you say so... quote:It's interesting because a bubble is caused by humans whereas a plauge is a natural event. The US bubble, in particular, was triggered by the behaviour of people and firms who knew that their social and political power would insulate them from the potential ramifications of their actions. I'm still not convinced you have a coherent definition for bubble. The countries sitting at the top of the GDP per capita list that have almost all been there for decades aren't bubbles. They have experienced bubbles but their economies aren't explained by bubbles. I already noted how China has grown through U.S. recessions and overall, developing economies were far less affected by the crisis and bounced back to pre-crisis growth quickly. The mechanics of trade and comparative advantage that are the basic drivers of export growth continue to work even when the rich countries stall out (which is basically what's happened in the last 7 years). China continued growing through the crisis and so did India:  quote:Honestly I find these statements a bit jumbled. I do not see how anything you're saying here relates to my comments about the financialization of major economies post-1970s. You'll have to clarify why you think this addresses anything we're talking about. The idea that Japan represents the future of the first world is possible. I just see no reason to think it is at this point. But comparing Japan to China makes no sense given the massive wealth disparity between them. China hasn't hit the middle income trap, let alone the upper income trap Japan occupies. Even if the entire first world stagnates it's another leap to decide that 1) that matters much to the rest of the world or 2) is a bad thing in the big picture (they've already been growing slower for decades). asdf32 fucked around with this message at 02:15 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

Bryter posted:Here's a neat bulletin from the Bank of England for anyone interested in how money is created. Although often terribly presented, I don't think the "multiply" model is worth throwing out as it captures certain mechanics and history of banking. Fractional reserve banking actually works on goods too. Imagine an economy where everything is based on grain. One older family may have saved a big pile of grain and one younger family may have almost none. If the older savers put their grain in a bank then the younger family can borrow it and eat it now. The younger family really has the grain and the older family behaves like they have the grain. Although no physical grain has been created there is a perception within the economy that the grain supply has increased. Among other places, fractional reserve banking evolved exactly like this except with scripts for gold. The thing with money is that it's virtual, so we accept that the increased perception of money really is an increase in the money supply. In general the basic model above is a pretty good example of the power and limitations of finance. It can be extremely powerful at making better use of resources that are available but it generally can't be credited with the creation of those resources itself. This paper seems to be combining this with some aspects of modern mechanics to make another leap in a model for systemic banking behavior. Wikipedia posted:In the past, savers looking to keep their coins and valuables in safekeeping depositories deposited gold and silver at goldsmiths, receiving in exchange a note for their deposit (see Bank of Amsterdam). These notes gained acceptance as a medium of exchange for commercial transactions and thus became an early form of circulating paper money.[6] As the notes were used directly in trade, the goldsmiths observed that people would not usually redeem all their notes at the same time, and they saw the opportunity to invest their coin reserves in interest-bearing loans and bills. This generated income for the goldsmiths but left them with more notes on issue than reserves with which to pay them. A process was started that altered the role of the goldsmiths from passive guardians of bullion, charging fees for safe storage, to interest-paying and interest-earning banks. Thus fractional-reserve banking was born. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 02:06 on Oct 14, 2015 |

|

|

|

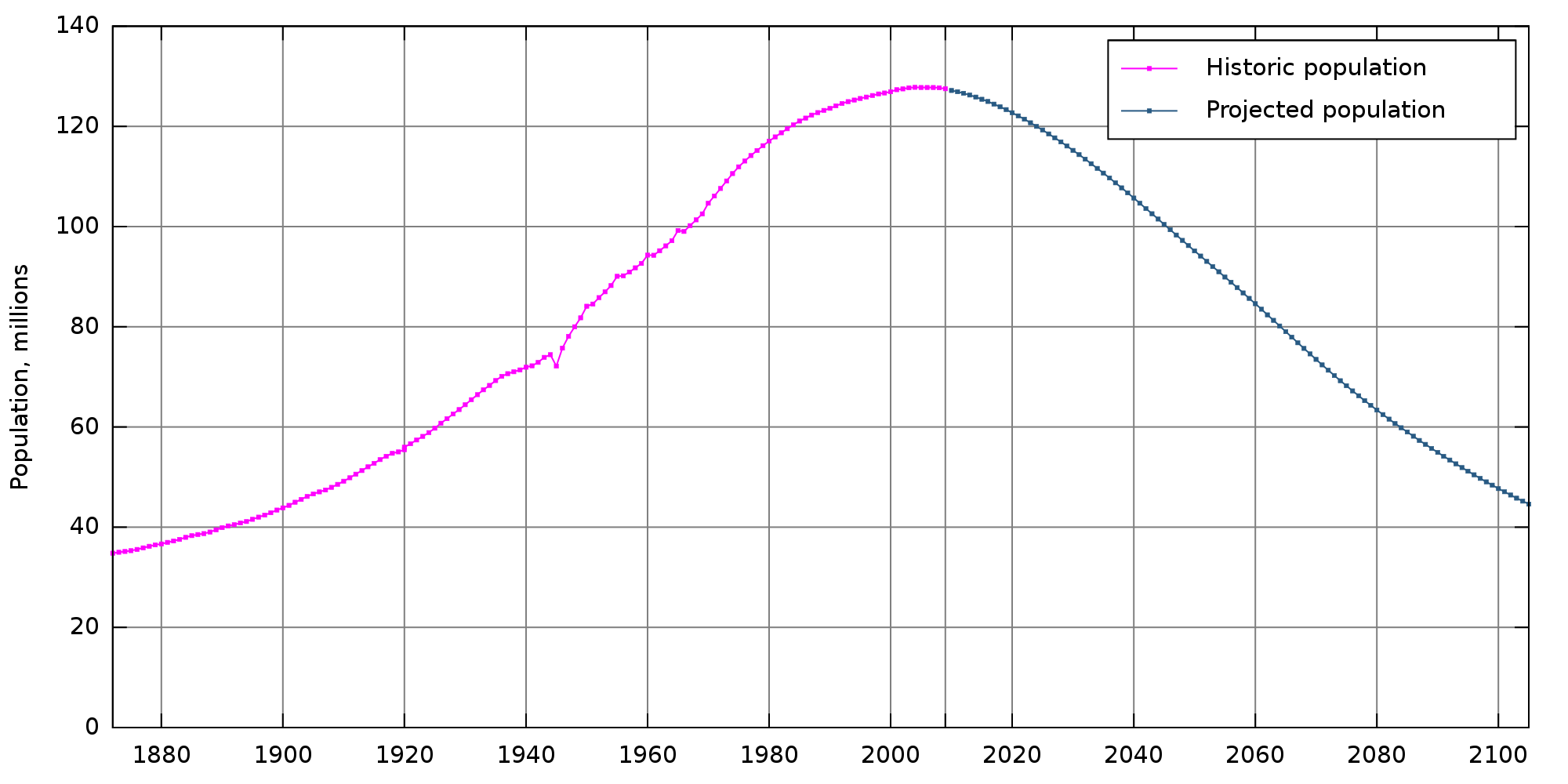

icantfindaname posted:pictured: no fundamental economic problem preventing growth: I was eyeballing demographics after my last post seeing how much they should impact things. If you try to come up with a number for GDP per worker things look slightly better for Japan but actually demographics aren't terrible yet. The workforce leveled off but so did population mostly (with population growing a little faster than workforce). So I don't think it's the main answer. Though it could be having a ripple effect. Well it's a pretty blurry line but there are certain separations between political and economic questions. For example general instability and corruption are political with economic consequences (and I think this generally explains why some poor countries can't get off the ground). Other economic policy like labor laws trade agreements, tariffs etc I'd say is both political and economic. Ardennes posted:Much of it is about demographics, specifically you need young people to consume (providing a domestic market) and hopefully work (feeding tax revenue back into the system). Ultimately, they need some time of income for this to work and yes, while growth is only part of the equation, you do want a expanding economy. (Sidenote: MMT falls apart when you get to issue of trade balances and exterior purchasing. Sadly enough Venezuela kind of killed MMT.) To be clear young workers save at a higher percentage than older citizens. An aging demographic increases demand relative to the workforce because they're not working and thus spending down savings on average (not to mention healthcare spending and government benefit payouts etc). The fact that demand isn't dominant in is the reason a younger and more productive workforce is beneficial for growth. If you're trying to connect an ageing demographic with lower demand that would be a mistake (I'm not quite sure if you are). That's not the problem of an ageing demographic. Bryter posted:It captures mechanics, but the wrong way around. Well it's fine to discard existing models for better ones. I'd just note that in this case it's not just a model, it's also history. Guavanaut posted:Like, capital demands growth, and you could theoretically deliver overall growth by forced breeding, wage slavery, and mandatory consumption, but I think we can agree that would be a pretty bad thing even if it delivered results. Much like under mercantilism you could secure ongoing growth by a process of stealing other people's poo poo. This is the type of financial junk that makes zero sense. If we could force growth we'd already be doing it all the time and if mandatory consumption were beneficial we'd print money and mail it to people but we don't for a myriad reasons. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 01:37 on Oct 15, 2015 |

|

|

|

Ardennes posted:https://www.google.ru/url?sa=t&rct=...0,d.bGg&cad=rjt Well relative to supply. When older people leave the workforce they stop producing (or produce less) but keep consuming. In the context of say China, where people like to point to their economy being unbalanced in terms of domestic consumption, an aging population could be a balancing factor by moving people from the the producer category to the consumer category. But it's true that this obviously shouldn't increase overall GDP. But it does something akin to stimulus from the perspective of the remaining workforce. Guavanaut posted:I'd hope we wouldn't if the only ways of doing it were abhorrent, although I suppose there's always going to be societies that try to prove me wrong on that one. Yes I think we're going to have to become comfortable with and prepared for declining or stagnant overall GDP in cases where the workforce declines. In that case we could shift to a metric of GDP per working age adult which will better capture the performance of the economy. Most people would want that number to continue going up.

|

|

|

|

No one in economics thinks a national $15 minimum wage is a good idea for a range of reasons based on real life research perhaps combined with a little bit of reason (this includes people like Kruger and Piketty).

|

|

|

|

Ardennes posted:Anyway, that obscures the fact that many if not most economists want a significantly higher minimum wage just not exactly a national $15 one. If anything most would probably be fairly happy with a $12-13 dollar national wage and a higher local wages on top of that. Ok. Most economists want it higher. Almost none want it at $15. quote:I think you are trying to say older people leaving the workforce will allow younger people employment and thus a greater ability spend? The problem though is they need everyone to constantly consume as much as possible, while older people no longer compete for the same jobs they also simply spend less that they once did at the same time. If you're trying to say that the chinese economy is unbalanced in terms of production capacity versus consumption an ageing demographic may help that. On you're next point you understand that GDP is money spent on goods AND money earned by people in the economy? So by definition they collectively have the earnings to consume their production. On top of that they also have huge financial reserves which could be used to consume if they had to be. The "problem", is that savings rate. They simply chose not to consume as much as they currently produce (thus relying on foreigners to make up the gap). Though note that in the long term, unless they represent a new breed of human, they're probably going to flip that switch at some point (otherwise they're essentially packaging and shipping us iphones for free). I'm arguing that it's not as much a problem as it seems because it's probably going to balance out at some point and in the short term the pattern of export they're following is not really in danger. EDIT: This captures two aspects of what I'm talking about. First, Korea was a huge saver like China while they were growing. That stopped and now they're notable consumers. Second, that savings rate decline coincided with retirement of an older generation. Effects of Population Aging on Economy and Car Market: http://www.koreafocus.or.kr/design2/layout/content_print.asp?group_id=104209  asdf32 fucked around with this message at 13:27 on Oct 16, 2015 |

|

|

|

Ardennes posted:Data shown above shows there is actually a lack of consensus on that fact at least on its effect on unemployment. I do think there is a wide band of opinions on the subject and a lot of it seems to be exactly which countries do they feel present better models. Krueger seems to prefer the UK and Krugman/Reich prefer a more Scandinavian direction. "They" are the humans in China and the institutions that represent them who's collective spending is domestic consumption. In regards to the question of whether the Chinese economy could consume it's entire output the obvious answer is yes and no, it doesn't matter whether it's government (or businesses) that are doing some of that consuming. Chinese people and domestic entities (representing Chinese people) earn the whole GDP. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 14:34 on Oct 16, 2015 |

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 30, 2024 23:58 |

|

Bryter posted:If you take the multiplier to mean that there's a hard limit on money/credit creation, I don't know that that's really ever historically been the case though. Concerns about solvency and profitability always seem to be the limiting factor. The destabilising effects of this on the money supply have been recognised for quite some time, and in Britain led to the passage of the Bank Charter Act 1844, which prohibited banks from issuing their own currency. This obviously didn't account for the fact that deposits work in basically the same way, and although money wasn't virtual in the modern sense, deposits could be created with a stroke of a pen, and the money moved around via cheques, essentially meaning banks retained their ability to create money. The multiplier doesn't imply a hard limit. The basic 1/R equation for fractional reserve money creation which textbooks love to present [even though that type of mathematical precision is irrelevant] allow near infinite money creation if you're willing to have tiny reserves. So of course solvency and profitability are the limits. And regardless of your model of banking behavior, the money supply is always practically bounded by the productive capacity of the econoomy. Exceed it, and inflation kicks in.

|

|

|