|

So starting a few years ago companies started charging for the high costs of fuel (airlines, deliveries, etc). I just noticed that my propane delivery had a $5 delivery charge so I started looking at fuel prices... Govt price tracking: https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=EMD_EPD2DXL0_PTE_NUS_DPG&f=M Turns out diesel is at it's lowest since may of 2009 and yet companies are still charging fuel surcharges. Right now I've got a complaint in with the propane company to find out when exactly do they actually stop charging for 'high' fuels costs. It made me start thinking about how much cash companies are bilking people out of simply because no one is really questioning it. Anyone know of any consumer protections regarding something like this?

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 16, 2024 20:59 |

|

Yeah, that's a pretty clear example of why companies won't pass the savings on to you. That being said, in lots of cases there's usually a fixed price contract negotiated, so regardless of the market price the people will pay the same amount for fuel. In this case, maybe your propane company has such a contract.

|

|

|

|

Not aware of any specific protections, but it's worth noting that a lot of the fuel surcharges have the stipulation that it will only be applied if fuel prices are above a certain rate. You'll still see the surcharge warning listed, but if the company is reputable you won't get charged unless the fuel actually does cost that much at the time the service is rendered. In my experience though, smaller fuel delivery services (e.g. home heating oil, propane, etc.) can be especially shady.

|

|

|

|

Oxphocker posted:So starting a few years ago companies started charging for the high costs of fuel (airlines, deliveries, etc). I just noticed that my propane delivery had a $5 delivery charge so I started looking at fuel prices... Just buy Home heating oil dude it's non-taxed non surcharged and it's Diesel #2.

|

|

|

|

Well my house is already setup for propane...so converting to oil would be counter productive. I talked to one of Como Oil's VPs and he said it was because the bulk carriers are charging them fuel surcharges, so they have to pass it on. But the guy agreed that there shouldn't be a surcharge, they have been trying to lobby through the MN truckers association to try and get it stopped. I do have a fixed price for the year on my propane (it's all prepaid) but the surcharges are separate from that. Overall it's only going to cost me like $20 for the year, it's not really the cost that bothers me...it's that everyone is paying a bullshit charge when fuel prices are so low because there hasn't been enough complaining about it.. Annoys me that complaining is about the only way that companies will listen to anything.

|

|

|

|

Oxphocker posted:Well my house is already setup for propane...so converting to oil would be counter productive. http://www.myshipley.com/learning-center/home-energy-guides/heating-oil-vs-propane

|

|

|

|

Prices are always sticky especially in cases like this where there are often contracts involved all the way down to the consumer level. Also many people are probably expecting prices to rise somewhat. But if raw prices do actually stay this low, it will propagate down the consumer eventually.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Prices are always sticky especially in cases like this where there are often contracts involved all the way down to the consumer level. Prices will only fall if there's some outside pressure upon the company to do so, such as competition from a rival company. If the firm has enough market power (either legitimately or through covert agreements with it's competitors) that it can set its own prices, and if demand for the good being sold is inelastic, then there's no reason to think prices will necessarily fall over time. For instance, the price of a drug called Daraprim was recently increased by more than 5,500 percent, from about $13.50 to $750 per pill. Likewise, the cost of educating a university student haven't increased anywhere near enough to explain the enormous increase in college tuition rates. In both these cases the fundamentals of supply and demand don't provide much illumination of why prices moved in the direction that they did. The point here being: these prices had almost nothing to do with 'supply and demand' and everything to do with the legal and institutional arrangements controlling the markets in which the goods were sold. Since basically everything produced in America these days come from a monopoly or oligopoly you can't just glibly assume that market forces will reduce prices over the long run.

|

|

|

|

Helsing posted:Prices will only fall if there's some outside pressure upon the company to do so, such as competition from a rival company. If the firm has enough market power (either legitimately or through covert agreements with it's competitors) that it can set its own prices, and if demand for the good being sold is inelastic, then there's no reason to think prices will necessarily fall over time. Good to know you've gone off the deep end. Just as a start have you purchased gas lately? It's plummeted to like $2/gallon around here. And what does "these days" mean? You think there was some golden age of market competition in the past? Let me guess - the 60's? asdf32 fucked around with this message at 03:18 on Dec 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Just as a start have you purchased gas lately? It's plummeted to like $2/gallon around here. Competing gas station are often literally across the street from one another. Competition is fierce in gasoline prices thus an "outside pressure" This is a very different situation from: tuition, heating oil, pharmaceuticals (especially for drugs that treat small populations.)

|

|

|

|

Hang on, Ya'll assuming billing has gently caress all to do with reality or production costs. Billing can be about controlling customer behavior and expectations. Even negotiated rates where both parties hash it out, still very often no loving connection at all to actual cost to perform the service or make the product.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Good to know you've gone off the deep end. I wish the invisible hand would pimp slap your dumb rear end. You dropped an ad hominem, a stupid analogy, and a "dumb hippie" insult (which is a loving idiot's ad hominem) all in the same post. Stop posting.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Good to know you've gone off the deep end. It's actually an interesting thing... back in (I believe the 90s) there was a economics bet between Paul Erlich and some economist I can't remember the name of at the moment about population and scarcity of materials. Paul bet that prices would go up after 10 years and the economist bet it would go down. They tracked several metals on the market and found out after ten years, the prices went down. However, one of the parts that a lot of people don't know is looking at prices during the 90s was also a bit of a blip because if prices had been extended out about 20-25 years, the overall cost would have gone up. It's still something being debated right now in economic circles because with globalization, massive corporations are wielding even more influence than before and are starting to act in oligarchist/monopolist ways which should be very disturbing to the average consumer. But since the average consumer doesn't know beans about how economic systems work, most people are in the dark beyond just very basic understandings. The issue of gas dropping has more to do with over supply issues at the moment because all this production ramped up once gas hit $4 a gallon. Since that production takes time to get to market, now we are seeing the effects of over supply. However, this isn't related to the heating oil/propane or other inelastic markets since it's not totally a supply issue. What I was getting at with the OP is that companies often use unfortunate situations to their advantage and will often continue milking such an advantage until forced to stop. But in some cases with sectors like heating, telecom, utilities, etc...there's no one to make them stop because switching services is either not possible or too onerous for consumers to bother so they take it up the rear for lack of a better option.

|

|

|

|

BrandorKP posted:Competing gas station are often literally across the street from one another. Competition is fierce in gasoline prices thus an "outside pressure" Which highlights how absent the billing specifics of heating oil brought up earlier the same industry is demosratively competitive with prices that can fall rapidly. I don't expect everyone to appreciate it but "These days [sweeping unsubstantiated claim like crime/terrorists/government/etc ]" is a form of argument which should set off alarm bells. The monopoly/oligarchy claim is less interesting alone because of definitional wiggle room but paired with "these days" it's a different story. But let's here it from others, when [before globalization and the internet] was the golden era of competition in America capitalism.

|

|

|

|

1760 through 1824

|

|

|

|

BrandorKP posted:Competing gas station are often literally across the street from one another. Competition is fierce in gasoline prices thus an "outside pressure" This strongly varies. Around here there's only three station brands who actually compete on price - Sam's Club, Costco, and Kroger. You can reliably count on any of those three being the cheapest in any area they have a station, by a large margin (minimum of $0.05, usually $0.10 per gallon or more). Two are warehouse clubs and the third is a supermarket chain, and that's not a coincidence. The actual gas-station-brand gas stations usually just match each other's prices rather than outright competing. Petroleum is a highly vertically integrated, oligopistic market which allows a lot of flexibility with where you realize your profits. A company like BP can effectively sell gasoline to their branded stations at almost exactly the retail price, which makes the retail margin "near zero" despite them realizing a pretty substantial profit with every gallon sold. The franchisees are locked-in to their parent company - a BP franchisee cannot just go out and buy gas from Shell. That's a major difference between the independent stations like Costco or Sam's Club - they can purchase the lowest-priced gas from whomever and compete on price, whereas a branded station cannot. In those cases it's not actually your local BP station setting prices, but actually the parent oil company, and that's an oligopoly who has no desire whatsoever to drive margins to zero. The franchisees mostly subsist on sales of soda and candy like movie theaters do, and the markets seem to have the same characteristic of a few powerful producers who can set prices to effectively capture almost the entire retail price. I've heard that Honda and Toyota used to have a similar scheme in the 80s (and probably does still). The US subsidiary would purchase cars from the parent company at full retail, which would mean that all the profits were realized in Japan instead of the US. Similarly, those US subsidiaries would have been a "zero margin" business that was still essential because it allowed the parent company to move large volumes of its product. Paul MaudDib fucked around with this message at 16:51 on Dec 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

Paul MaudDib posted:This strongly varies. Around here there's only three station brands who actually compete on price - Sam's Club, Costco, and Kroger. You can reliably count on any of those three being the cheapest in any area they have a station, by a large margin (minimum of $0.05, usually $0.10 per gallon or more). Two are warehouse clubs and the third is a supermarket chain, and that's not a coincidence. Accounting tricks are unrelated to competition. The simple fact is that retail gas prices have rapidly plummeted which (and we all agree on this) can only happen because of competition. It's pretty simple. Yes sometimes rural areas have higher prices. This isn't news on any front. But note that US gas prices are still low in low population density states like Oklahoma, currently averaging $1.71/gallon, which would presumably have the weakest competition (prices seem dominated by tax variations which is completely consistent with a competitive model).

|

|

|

|

Oxphocker posted:It's actually an interesting thing... back in (I believe the 90s) there was a economics bet between Paul Erlich and some economist I can't remember the name of at the moment about population and scarcity of materials. Paul bet that prices would go up after 10 years and the economist bet it would go down. They tracked several metals on the market and found out after ten years, the prices went down. However, one of the parts that a lot of people don't know is looking at prices during the 90s was also a bit of a blip because if prices had been extended out about 20-25 years, the overall cost would have gone up. It's still something being debated right now in economic circles because with globalization, massive corporations are wielding even more influence than before and are starting to act in oligarchist/monopolist ways which should be very disturbing to the average consumer. But since the average consumer doesn't know beans about how economic systems work, most people are in the dark beyond just very basic understandings. That was Julian Simon, one of the Reaganites' favorite economists for writing incredible nonsense about how recycling and science mean that the supply of natural resources is effectively unlimited.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Accounting tricks are unrelated to competition. The simple fact is that retail gas prices have rapidly plummeted which (and we all agree on this) can only happen because of competition. I would disagree. Competition is not the only factor at play. For gas specifically in this instance, we are looking at an over supply issue, not a competition issue. Natural gas would be another good example of oversupply driving down prices. Also, one of the factors going into gas prices in the US is location to nearby refineries, which you will see lower prices because of less transportation needed. Many of the refineries in the US are located in/around Texas, so seeing lower prices in OK and the south is not all that uncommon. As for the Erlich/Simon bet (thanks Pope for the name), while Simon was eventually wrong to a certain degree it shows what technology can do to improve efficiencies and lower costs. Erlich's original statement in the Population Bomb was basically that we were overpopulating the Earth and at some point we would run out of resources. But technology has shown this isn't quite the case and with the economics of the 90s at play, prices actually went down for a time. The problem often times is that many economist and policy makers are often married to a single economic philosophy which when you actually look into those philosophies are often based on specific cases instead of general rules. Once you apply them in a general context, often times the realities of the world make it impossible to keep consistent to the theory. For example the conservative idea of supply side economics. Sounds great in theory, reduce taxes on the wealthy to have that wealth trickle down into the economy. Except we know that's untrue....what happens is the wealthy horde the wealth and very little gets into the economy. You only have to look at the growing wealth gap in the US to see evidence.

|

|

|

|

Oxphocker posted:I would disagree. Competition is not the only factor at play. For gas specifically in this instance, we are looking at an over supply issue, not a competition issue. Natural gas would be another good example of oversupply driving down prices. If proximity to a refinery or over-supply, or any other supply side cost reduction (technology) translate into lower retail prices it's because of competition.

|

|

|

|

Fuel surcharges (which are, as noted, very distinct from gas prices) tend to result from competition, not monopolistic behavior. In a monopoly or small oligopoly, the entity/entities that control the market can just say, "gently caress you, prices are going up." You don't have a choice, so you pay the increased price. In a competitive marketplace, though, competitors have an incentive to hide the actual cost of their product. For instance, look at airlines, one of the worst abusers of fuel surcharges (as well as plenty of others). It's an industry where people buy on price and often comparison shop with third-party tools like Kayak and Expedia. The airlines all want to have the "cheapest" price, so they offload the real cost into fees, and advertise "$99" flights that come out to $300 once you're actually on the plane. Shipping services are the same way; it's a naturally competitive market, because a shipping service has to go to lots of places, almost by definition. So, there's incentive for buyers to comparison shop, and a corresponding incentive for shippers to offload the real cost into fees and drive down the list price.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Good to know you've gone off the deep end. We're not debating whether the price of gas fluctuates, we're debating what forces cause prices to adjust up and down. Specifically I'm arguing that you cannot invoke a simple supply and demand argument without accounting for several other key factors, which I listed above. If you have an actual substantive response I'd love to hear it. The impact of increased market power has been studied and the results tend to be higher prices, which again would suggest that a simplistic invocation of 'supply and demand' is a totally insufficient explanation for why prices move up and down: Does merger control work?, northeastern.edu posted:Specifically, Kwoka analyzed the details of more than 40 mergers with measured price outcomes, including 1999’s Exxon-Mobil merger and Whirlpool’s 2006’s acquisition of Maytag. He supplemented this data set with information pertaining to the actions taken by U.S. antitrust agencies with respect to those particular mergers—whether they were cleared, opposed, or approved with remedies. quote:And what does "these days" mean? You think there was some golden age of market competition in the past? Let me guess - the 60's? I don't know why you would think that I'd hold the 1960s up as some kind of "golden age" to be emulated, though it does fit this trend of you obnoxiously assuming I'm making arguments that aren't contained or even hinted at in my posts. As to the substance of your question, the fact is that since the 1980s the way that monopolies and oligopolies are regulated in the USA has changed dramatically, in part thanks to the influence of Chicago school law and economics programs on the government's regulatory philosophy, and also thanks to changes implemented during the Reagan administration. These changes caused the US government to take a more benign view of economic concentrations and monopolies than in the past and helped accelerate already existing trends toward consolidation. If you want a book length treatment of this issue check out 'Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction' by Barry C. Lynn. There are also discussions of this phenomenon in the business press. Here, for instance, is a short opinion piece that appeared in that noted commie rag, the Washington Post: quote:

|

|

|

|

Oxphocker posted:Well my house is already setup for propane...so converting to oil would be counter productive. Mom and pop propane companies are the used car dealers of the energy market. I had natural gas from the incumbent provider for my whole life up until 2 years ago when we built out in a exurb that didn't have natgas service. Now I'm using propane, and I've had more conversations with my provider about my bill in that time than I did in 20 years of bills (since I've been paying them anyways) from Niagara Mohawk/national grid. Everything is a scam and you have to watch them like a hawk.

|

|

|

|

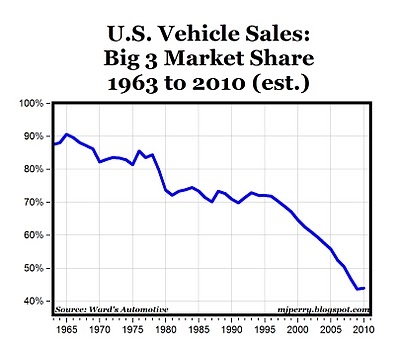

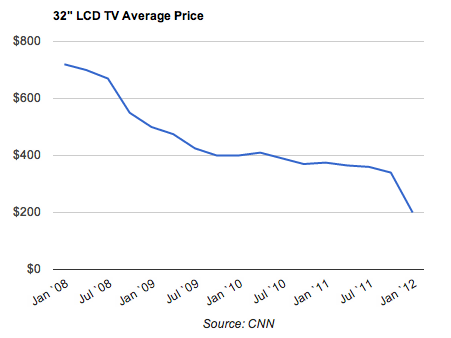

Helsing posted:We're not debating whether the price of gas fluctuates, we're debating what forces cause prices to adjust up and down. Specifically I'm arguing that you cannot invoke a simple supply and demand argument without accounting for several other key factors, which I listed above. If you have an actual substantive response I'd love to hear it. Level of competition is a sliding scale. In real life we reserve the terms monopoly and oligarchy for things beyond just the lack of theoretical perfect competition. A statistically significant increase in business size and market power wouldn't substantiate the claim that "basically everything produced in America these days come from a monopoly or oligopoly". Or if we do define those terms as lack of perfect competition, we've made them useless. The nice thing about this thread is that there is a specific topic, fuel prices in which we can easily observe the price decrease and examine the reason - increased supply (North American production and Opec's reaction) and when increased supply leads to lower prices competition is the model that explains it. You're not claiming that there was a monopoly bust in the industry recently are you? The broader industry is clearly competitive, which leaves contract structure of heating fuel, which as pointed out is literally deisel fuel with a different tax, as the main difference. A change in policy towards monopoly isn't an argument for the result you described. Since the 1980's we've also had global competition come on in full force and have [sometimes international] internet retailers and manufacturers competing with U.S. businesses on almost every retail good. Prior to the 80's people were forced to purchase primarily domestic or local goods because transportation simply wasn't good enough to open up wider competition at scale. U.S. car manufacturer share of the market captures this trend nicely - a trend which played out in countless areas of heavy industry (Japanese steel, Hyundai cranes) and consumer facing industries like home appliances, furnishings and obviously electronics.  In the tech sector, price decreases have been rapid enough to be called delfationary  It's true that businesses are getting bigger but the implication of that isn't automatically clear. 538 analyzed the trend and doesn't find an associated increase in profitability Big Business Is Getting Bigger posted:If big business is getting bigger, it’s not necessarily getting more profitable. The ratio of Fortune 500 profits to all corporate profits shows a cyclical pattern. That is, they are very high in good years, and plunge in bad years, but with no real upward trend. And again whether, increased business size has effectively concentrated market power is a separate question Big Business Is Getting Bigger posted:With a slew of mergers and acquisitions — like the Verizon-AOL deal — big businesses might be snapping up or joining with rivals, and that corporate consolidation may have led to a concentration of market power. That’s the skeptical-of-business view. http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/big-business-is-getting-bigger/ Since we've talked about labor in the past and this hits on price models very directly, I'll throw in this study which specifically went looking for monopsonyin the labor market and more broadly, sought the best model for predicting wages. The conclusion: no detectable monopsony/competition best explains wages. quote:We interpret these findings within a simple yet quite general model of employment determination asdf32 fucked around with this message at 23:57 on Dec 30, 2015 |

|

|

|

Helsing posted:Prices will only fall if there's some outside pressure upon the company to do so, such as competition from a rival company. If the firm has enough market power (either legitimately or through covert agreements with it's competitors) that it can set its own prices, and if demand for the good being sold is inelastic, then there's no reason to think prices will necessarily fall over time. Tuition prices may not have much to do with the cost of educating a university student, but that has nothing to do with supply or demand. What does matter, on the other hand, is that there is more than enough demand to more than fill the finite supply of student capacity, particularly since there are a number of forces artificially pumping demand.

|

|

|

|

Main Paineframe posted:Tuition prices may not have much to do with the cost of educating a university student, but that has nothing to do with supply or demand. What does matter, on the other hand, is that there is more than enough demand to more than fill the finite supply of student capacity, particularly since there are a number of forces artificially pumping demand. Yes, a supply and demand model works when competition isn't perfect. I believe helsing was rolling competition, supply and demand together though they are distinct In the case of education, much like healthcare, supply and demand are valid models but perfect competition is less useful. In both cases you essentially have a broken consumer market. Wide eyed potential students and parents show up to campuses and don't properly evaluate price (because they may have ample subsidies or are thinking in idealistic terms about future potential). Same with the healthcare 'market' where the end consumers have no incentive (or even the necessary knowledge) to be price conscious. If Helsing want's to highlight this fact, that decent chunks of spending like housing healthcare and education are non-markets that's obvious. I don't believe it adds up to a majority of the market. And in the context of this thread where we're actually talking about a specific good with demonstrably competitive pricing behavior I took his original statement to be far stronger. If the target was intended to be wider I think it's wildly out of touch to imply that basic consumer goods like automobiles, appliances and computers aren't competitive. And if that is the argument let's drop the examples from healthcare and education. The drug Daraprim by the way is a tiny drug that had a total of $667k in sales in 2010. It's not an example that generalizes well to more important drugs because more important drugs will already have multiple generic suppliers. Daraprim does have generic suppliers globally, just not certified in the U.S. yet. And the high barrier of that certification is what makes this example terrible for generalizing anything outside medicine.

|

|

|

|

asdf32 posted:Level of competition is a sliding scale. In real life we reserve the terms monopoly and oligarchy for things beyond just the lack of theoretical perfect competition. A statistically significant increase in business size and market power wouldn't substantiate the claim that "basically everything produced in America these days come from a monopoly or oligopoly". Or if we do define those terms as lack of perfect competition, we've made them useless. The fact is that market power is concentrated enough in America today that many industries are dominated by what experts would term monopolies or oligopolies. Go ahead and google Luxotica. Tell me how you'd classify their role in the marketplace. quote:The nice thing about this thread is that there is a specific topic, fuel prices in which we can easily observe the price decrease and examine the reason - increased supply (North American production and Opec's reaction) and when increased supply leads to lower prices competition is the model that explains it. You're not claiming that there was a monopoly bust in the industry recently are you? The broader industry is clearly competitive, which leaves contract structure of heating fuel, which as pointed out is literally deisel fuel with a different tax, as the main difference. How did you manage to mention OPEC literally moments before writing this sentence without realizing how self defeating your argument is? OPEC was a cartel, not a monopoly, but surely I don't need to explain to you how that would seem to support the argument I'm making that market power rather than supply is often what drives pricing decisions? Don't you get that the 'supply' here was being artificially manipulated through collusion by producers, and that prices then dropped when this collusion broke down? Then you write that "the contract structure" is the key difference here. Again, it's not clear to me whether you understand that the way contracts are written and enforced is one of the factors I was citing earlier when I said taht a simple supply and demand model is woefully insufficient for explaining price changes. As to the rest of what you're saying. No offense but are you sure you understand what I'm even arguing here? You understand that we're not debating whether or not the price of fuel inevitably goes up or down. I think we both recognize that prices fluctuate over time. What we're debating -- or at least my understanding of this debate -- is what underlying factors or mechanisms are driving the changes in price. quote:A change in policy towards monopoly isn't an argument for the result you described. Since the 1980's we've also had global competition come on in full force and have [sometimes international] internet retailers and manufacturers competing with U.S. businesses on almost every retail good. Prior to the 80's people were forced to purchase primarily domestic or local goods because transportation simply wasn't good enough to open up wider competition at scale. U.S. car manufacturer share of the market captures this trend nicely - a trend which played out in countless areas of heavy industry (Japanese steel, Hyundai cranes) and consumer facing industries like home appliances, furnishings and obviously electronics. I don't see why you feel all this is relevant to our argument. If you want to dispute that the US is dominated by monpolies then don't bring up some spurious and insubstantial comments on globalization. The fact that the economy became more globalized in the same time period that firms were increasing their market power is irrelevant to our argument, so far as I can tell. If you want to dispute that changing regulations lead to greater concentrations of corporate power then show me some industries where this didn't happen. Just going "b-b-buuut globalization!" isn't an insightful or meaningful rejoinder to anything I've argued. quote:In the tech sector, price decreases have been rapid enough to be called delfationary Jesus Christ. Did you seriously think my post was arguing that prices only ever increase in our economy? I mean, no wonder you said you thought I had gone off the deep end. You might as well be debating a wall because you sure aren't addressing the actual arguments I am trying to make. I guess part of that might be my fault but honestly I feel like I've been pretty clear. So when you start this conversation off by insulting me and then you proceed to demonstrate utter carelessness regarding what I said it makes me question how worthwhile these debates actually are. You just don't seem to put any effort into reading other peoples posts. quote:It's true that businesses are getting bigger but the implication of that isn't automatically clear. 538 analyzed the trend and doesn't find an associated increase in profitability But we're talking about prices? No one in this thread ever said anything, one way or the other, about increasing profitability. quote:And again whether, increased business size has effectively concentrated market power is a separate question That's the question we're debating though. I don't know why you're bringing up this tangentially related stuff about globalization or profitability when we're debating the best theoretical framework for understanding price movements. Instead of just posting your own graphs and links could you reply to the academic studies I cited which show that greater market power does lead to price increases? You basically ignored all the details of my argument and went off on some unrelated tangents instead. quote:Since we've talked about labor in the past and this hits on price models very directly, I'll throw in this study which specifically went looking for monopsonyin the labor market and more broadly, sought the best model for predicting wages. The conclusion: no detectable monopsony/competition best explains wages. First of all the labour market is hardly the ideal comparison for the market in consumer goods. Furthermore, this study very explicitly doesn't deal with the labour market in general: the authors make it clear that their results are both 1) fairly weak and 2) apply only to food services employing minimum wage workers. p. 690 posted:To be clear, as Boal and Ransom (1997), among others, point out, our results do not necessarily prove labor markets are competitive. Although the results are clearly consistent with this conclusion, if the minimum wage is set high enough, positive comovement between the minimum wage and prices may be consistent with the monopsony model as well. Finally, it is important to emphasize that our estimates are for the restauraunt industry only. This industry is a major employer of low-wage labor and therefore a particularly relevant one to study. [/quote] p. 706 posted:It is important to note that if firms are monopsonists in the labor market but the minimum wage is set sufficiently high (above w** in Figure 2), employment is determined by the intersection of the minimum wage and the marginal product of revenue curve. In this case, an increase in the minimum wage increases prices and reduces employment, just like in a competitive labor market. Thus our empirical results cannot necessarily disprove the existence of monopsony labor markets in cases where the minimum wage is set high (above competitive market-clearing levels). However, we believe our empirical results should temper enthusiasm for monopsony power being the explanation for the negligible employment responses found in the literature. Finally, the actual way in which these conclusions are reached is questionable at best since it relies very heavily on economic models. Basically it uses economic theory to derive a bunch of conclusions about how the labour market ought to respond, then it takes a small amount of empirical data (in this case covering a three year stretch) and tries to fit that data to the model. This is particularly clear when you read their conclusion: p. 712 posted:V. Conclusion The argument here is that because minimum wages did not lead to an increase in employment and a decrease is prices. Since they didn't find evidence of that in their study they conclude that the market is competitive. Of course we might want to question the underlying model of monpsony they're using. Given that it's New Years Eve I do not have the time to do a reread of the paper or to look up the theoretical models they're relying on to critique them in more depth, and after all you are the one who cited this paper so really it's on you to justify their methodology, but suffice it to say that I find the approach they are employing questionable at best -- though to the credit of the authors, they're very reserved in terms of declaring what the implications of their work are. We can revisit this paper at greater length if you really want to get into the weeds of how economic studies should be conducted or what the relationship between high theory and empirical research ought to be. But fist I'd ask that rather than debating a single contentious study with weak results dealing with an extremely atypical market (i.e. in human labour) perhaps I could ask you to craft a substantive response to the studies I mentioned which find that increased market power via mergers correlates with price increases. Or perhaps you could respond to the specific examples I gave of companies like Luxotica. asdf32 posted:Yes, a supply and demand model works when competition isn't perfect. I believe helsing was rolling competition, supply and demand together though they are distinct Jesus Christ, your reading comprehension is terrible. How could you possible read my first post in this thread and not understand that I'm obviously treating supply and demand as distinct from competition? I mention them as distinct entities and in fact suggest that competition, rather than supply and demand, is often a better explanation for driving price changes. quote:

And what is it that creates these high barrier to getting certification? Why, could it possibly have anything to do with: Helsing posted:the legal and institutional arrangements controlling the markets in which the goods were sold. Daraprim is an extreme example of how the market in pharmaceuticals normally functions, which is exactly what makes it useful. It's the same reason that engineers spend lots of time studying plane crashes, even though the vast majority of planes don't crash: because when something goes catastrophically wrong we can study it and gain a better understanding of how the system normally functions.

|

|

|

|

Helsing posted:The fact is that market power is concentrated enough in America today that many industries are dominated by what experts would term monopolies or oligopolies. Ok so it might help to find someone else making claims as sweeping as your own "basically everything....these days" quote:Go ahead and google Luxotica. Tell me how you'd classify their role in the marketplace. And I think you're confused. Go back and read the thread, from the OP: "Turns out diesel is at it's lowest since may of 2009 and yet companies are still charging fuel surcharges". So here we have a recognition that the underlying commodity has already decreased in prices [we no longer care why] all the way down to the consumer. Oil has dropped and diesel fuel, which is actually identical to heating oil, hasn't. Now I'm not quite familiar enough with this market to know where exactly in the distribution pipeline diesel fuel and heating oil diverge but I'm assuming it's not too far upstream. So that means we're basically talking about last mile distribution - mom and pop heating oil companies. Are they generally competitive? Yes because most of the population lives within range of multiple delivery companies. So what's the difference then? Probably contract structure where heating oil is on longer term contracts that are re-evaluated less often. Now this is where you chimed in with sweeping statements about lack of competition - in the context of oil delivery companies. OPEC is irrelevant - the path from the underlying commodity to the consumer goes through competitive retail channels. Contract structure: Really? It's obvious that if I sign a year long contract supply and demand is no longer setting my prices. But it dictated the terms of my original contract and my next one. It's a slower market, it's still a market dictated by supply and demand. quote:I don't see why you feel all this is relevant to our argument. If you want to dispute that the US is dominated by monpolies then don't bring up some spurious and insubstantial comments on globalization. The fact that the economy became more globalized in the same time period that firms were increasing their market power is irrelevant to our argument, so far as I can tell. If you want to dispute that changing regulations lead to greater concentrations of corporate power then show me some industries where this didn't happen. Christ, how is globalization 'spurious' when the choices faced by actual american consumers are entirely global. If Ford and GM merged tomorrow it might, per your source, raise prices a detectable amount but it's not a monopolized market when over half the share would still be made up by competitors from places like Germany, Japan and S Korea. We're not holding real life competition up to theoretical standards. Detectable price changes (within limits) in response to changes in competition are consistent with real life competitive models. Meeting a useful definition of oligarchy takes further evidence and globalization is highly relevant to the overall competitive landscape. I'm not sure why you think Luxottica is such a powerful an example. Quickly checking glasses numbers I put the U.S. market at about 20 billion compared to gross global luxotica sales of 7 billion. They don't control close to half the U.S. market in sales and retail locations for glasses sales are actually dominated by local optometrists. Have you heard of Warby Parker (my wife wears these) or Zenni optical (my friend uses them)? They exactly fit the narrative I outlined earlier of what the implications of both globalization and the internet are. Warby Parker is an independent online competitor (a successful one) and Zenni optical is direct from China. And this isn't a very protected industry. The thing that made the Daraprim example so extreme was protection. Competition can be effective with nothing more than a credible threat. If Daraprim had one supplier but no regulatory protections those price increases wouldn't have happened. Barriers of entry are a critical ingredient to monopolistic behavior which is why the reality of both globalization and more recently the internet is so relevant. Especially when you're trying to make claims about historical trends. Again, step back for a second and consider that prior to the 80's (your dividing line) american consumers relied primarily on U.S. made goods supplied by the handful of retailers that happened to be local (and the farther back you go the more local it was, especially before the 60's introduction of the highway system). The transformation that's taken place since then is that we have a combination of national and international retailers competing alongside local ones with all of them now selling a globally sourced basket of goods while competing against direct online competitors in almost every category. This is the context in which you're saying "these days"..competition is worse. I'm not sure you're grasping the implications of this but I think most consumers do. My household spending is split quite broadly between my local hardware store, the Home Depot that's farther away and a couple online retailers and includes brands from Germany, S Korea, Japan and the U.S. Wal-mart is a peice of the trend I'm describing and despite controversy, is widely accepted to have produced a measurable decrease in prices: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.508.3777&rep=rep1&type=pdf quote:Jesus Christ. Did you seriously think my post was arguing that prices only ever increase in our economy? I mean, no wonder you said you thought I had gone off the deep end. You might as well be debating a wall because you sure aren't addressing the actual arguments I am trying to make. I guess part of that might be my fault but honestly I feel like I've been pretty clear. So when you start this conversation off by insulting me and then you proceed to demonstrate utter carelessness regarding what I said it makes me question how worthwhile these debates actually are. You just don't seem to put any effort into reading other peoples posts. Ok you get that in an inelastic market (fuel) there is near zero incentive to decrease prices other than competition? So the existence of price decreases is actually relevant. Second what the hell do you think drives plummeting prices of TV's if it's not competition. That graph is not the behavior of a monopolistic market which makes it highly relevant to the claim "Basically everything...." quote:Instead of just posting your own graphs and links could you reply to the academic studies I cited which show that greater market power does lead to price increases? You basically ignored all the details of my argument and went off on some unrelated tangents instead. I already addressed this in several ways above. Yes competition changes may change prices but in small amounts that's not useful indication of oligarchy and certainly doesn't entirely describe any trend one way or another (is a merger one step back in a context of 3 steps forward) The wal-mart impact on prices does actually describe an overall trend (in an important segment of the market). Finally, where the hell do you think increased prices go if not profit? Profit, and specifically profit of the large companies that are the result of mergers is a great place to look for signs of the claims you're making. quote:First of all the labour market is hardly the ideal comparison for the market in consumer goods. Furthermore, this study very explicitly doesn't deal with the labour market in general: the authors make it clear that their results are both 1) fairly weak and 2) apply only to food services employing minimum wage workers. I may come back to the study if I have more time. One thing to get is that their model of monopsony originates as a proposed explanation for pro minimum wage findings (and I think they explain it quite well as well as justify their belief that the monopsony model holds) . I don't know why you say their findings aren't strong when they fairly robustly demonstrated labor cost pass through to prices. That's an important empirical finding independent of the model discussion. asdf32 fucked around with this message at 20:16 on Jan 1, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 16, 2024 20:59 |

|

I'm coming back and trying to clarify a few things to keep this on trackquote:That's the question we're debating though. I don't know why you're bringing up this tangentially related stuff about globalization or profitability when we're debating the best theoretical framework for understanding price movements. It is? The statement I jumped on was the duel claim you made about market conditions (monopoly/oligopoly) and, more importantly in many ways, the implication that it's getting worse. quote:Daraprim is an extreme example of how the market in pharmaceuticals normally functions, which is exactly what makes it useful. It's the same reason that engineers spend lots of time studying plane crashes, even though the vast majority of planes don't crash: because when something goes catastrophically wrong we can study it and gain a better understanding of how the system normally functions. Ok but understand that the statement you made, which I primarily reacted too was the equivalent in my mind to "planes aren't safe these days". First I disagree with the not safe part. Here examples of individual crashes (Daraprim, Luxxotica) are relevant but anecdotal. Statistics would be better but ultimately 'not safe' is a judgement call where your definition might differ from mine (I did try to address the definition of monopoly/oligopoly in a few ways). But to the second part, the implication of a trend, is more interesting and less subjective and here individual events are irrelevant. Millions of Americans are absolutely convinced that crime is increasing, the world is less safe, pedophiles are going to abduct their kids etc because they're remembering individual events they saw on the local news. The events happened but the interpretation of those events into a narrative of decline is fictitious with far reaching political/idological consequences and the paralel between your statement and this example in my mind is what elicited my strong response. Daraprim and Luxottica are individual 'events' and your data that merger events correlate to price increases also actually tells us nothing about a potential trend (or even an existing state). It can be true with few implications which is why I didn't spend a ton of time on it - are mergers new (no) are they increasing (?) and what's the broader context (I focused on this). Helsing posted:And what is it that creates these high barrier to getting certification? Why, could it possibly have anything to do with: I skipped this earlier because I don't get it. If you want to make the observation that any average price of a good in a store has a regulatory component too it, or that more broadly the entire market is shaped by government/regulation that's fine..But the statement you originally made was about monopoly and oligopoly. I generally consider the regulatory environment to be external to the market while monopoly and oligopoly are internal too it. The fact that there are regulatory requirements, costs and barriers to drugs certainly has a huge impact on prices, but it doesn't say anything one way or another about a monopoly or oligopoly. Many generic drugs have very healthy competition.

|

|

|