|

Yuiiut posted:Can't wait till having our Franco-Prussian war before the landowners got their restoration itch scratched causes us restore the Purgyals permanently. It's over on the Paradox forums, but my megacampaign got through Vic2 with an intact monarchy. I'm still in the HoI4 phase, so spoilers about that phase.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 15, 2024 19:03 |

|

Pretty sure the Hohenzollen one Wiz ran years ago was all monarchy all the time.

|

|

|

|

Is V3 really not very well liked? It seems like it has a lot of cool ideas, but idk how they translate into a working game.

|

|

|

|

V3 needs another year or two of cooking, and a DLC or three. Much like most PDox games, really.

|

|

|

|

It's definitely better than release. The patches so far have been substantial and the new military systems look promising but I have not actually played any 1.5 versions yet. I could well have waited a few more months before starting modding work but the earliest versions are still workable.

|

|

|

|

GunnerJ posted:Is V3 really not very well liked? It seems like it has a lot of cool ideas, but idk how they translate into a working game. There's a mix of genuine dislike for it in specific but probably more broadly of the 4 mainline Paradox series (CK, EU, V, and HOI), Vicky has generally been the least popular. CK focuses on characters in a way that really rewards people who like the roleplaying angle, EU is the king of mappainting, and HOI has a lot of combat depth. By contrast Vicky has always focused on internal development: flows, supply-demand, investment, etc. Like not even directed critical antipathy, its just not typically as good at sparking the imagination of a lot of people as the other 3. It definitely has fans, its my favorite, but it has never and probably will never have as big a fanbase as CK or EU even if it executed on its intended ideas perfectly (which it definitely has not).

|

|

|

|

"What good is Lhasa? I ask you this most sincerely -- what good does Lhasa produce for the whole of the Republic? A cold, windswept city atop the mountains where the only thing to come from it is words -- words of prayer on the winds, words of law on paper and slate, and words of war to armies and weapons-makers. What right does the Red Mountain Party have to sit perched in the clouds and speak to us of tradition and virtue, to tell us that we have sinned to follow the word of Allah or the teachings of the gurus? They tell us as such because if they were to stop speaking, if the words were to stop flowing, then they would have nothing to stand on and Lhasa would fall from the mountains." -Chandranath Mokammel, founder and owner of the Mokammel Peerless Cotton Weaving Company of Dhaka

|

|

|

|

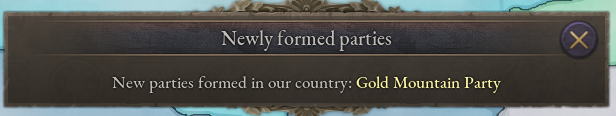

Chapter 89: 1845 to 1853 - Church and State The unpublished and unedited draft of a memoir of Sonam Rinzin, Tibetan ambassador to the Republic of Wu and the Huabei Federation, is continued here. These assorted sections include a discussion of the contemporary Tibetan-Huabei War, and some scattered notes on Tibetan domestic politics of the period.  In the first months of 1845, the war continued in the same labored manner as it had for the last two years. Armies fought in the Red Basin and past the western loop of the Hetao.  The Sacred Hierarchy, exhausted in the field of battle, announced independently, and without my knowledge, that it had signed a separate peace with the Huabei Federation.  The new Sacred Hierarch, Chodha Khun, as I would learn from letters and my associates who now were assigned to that court, was a sprightly and disciplined man. He was not at all who I would expect as a leading religious figure. He was some 40 years of age, with some hair not yet grey. With this energy, he would publish speeches and commentaries on the virtues of a swift end to the war, and justifications for a 'new turn of the wheel' in the relationship between the Hierarchy and other states. This was an understandable position to take, and frankly an enviable one - not all of us were fortunate enough to live in the same prosperous and quiet neighborhood on the map of the world that he did.  The war had become exhausting news in Nanjing, a cause of exhaustion rather than some other suffering. Those gentlemen and ladies who still could hold their tea parties had grumbled about prices, although only a few about lost relatives, and frankly wanted the drat thing to be over. Topics of discussion at parties were at times about the war, though there were some who insisted on about anything else - everything else - even the remotest corners of the world. One of the most outstanding was a revolt aganst the Tlaxcalalteca colonies in distant Yorop. It had become a celebrated cause among those intellectuals, those students of the great academies that remained, and those who read stories in the back of the newspapers to loudly root for distant rebels and for the establishment of a republic.  I have never spoken to an Anglisch person, and the stories of such a distant country were a novelty to me as the surface of the moon. However, the distance of a place and the stories about it adds a fairy tale notion, right out of the marvelous fiction of the old Classic of Mountains and Seas, and on more than one occasion I was able to placate a tense conversation at a dinner party with talk of the cavalry charge of the distant shield-maidens of Anglaland and a toast to their distant bravery.  But to return to affairs of state, the war had ground to a halt in the distant loess plateau of the north, hearing of spilled blood and choking on the red dust of this earth.  I could only read the correspondence that had informed me of each new development, and hearing of the failure of the barley and buckwheat in the highlands of western Tibet was something that would only cloud my thoughts further. To quote from a friend who had written me with stories she had heard from Ngari: "It is impossible to describe the conditions in the far west that the people endure silently: where the sheep and goats have died, where all foods save stale barley have vanished and that is rapidly failing."  To compound on this ill, the war drags on interminably. The army of the Tibetan Republic had launched a counterattack in Sichuan near Deyang, south of Mianyang, which had after a valiant defense had fallen. That attack then ground to a halt in the fence of entrenchment and fortifications and the sheer weight of numbers. To quote a friend of mine who later wrote to me about the battle, and whose account I shall copy out: "The advancement of the troops of the armies was beautiful, perhaps clockwork. The ground had become dark as the black earth around volcanos, suffused with fissures and chasms from the artillery fire and the rows of thousands of muskets, showering down upon us." The battle was still a loss - the company retreated with heavy losses, and my friend had only survived because the man in front of him was torn to pieces by shrapnel and not his own body.  Then, to my astonishment, I had, through informers and other documentary sources, received word that the Anatolians, the great power and the fulcrum of the war front in the very north, were withdrawing from the war. This was a moment of total surprise. Had the war grown too ruinous to them, and had I completely failed to anticipate their exhaustion? Was there some alternate unknown cause for them to pull the armies back? As it turns out, it would be the latter.  In a speech that was then read out to all of us foreigners in the diplomatic services, from a thick-jowled officer whose hat wobbled like a child's wooden top. He recited in a rumbling toneless voice, that for the safety of the republic and its people, a military government had been established on a temporary basis to restore order and to preserve the legal and constitutional rights enshrined since the first revolution. Aramais Melik-Aghamalian, the same head of state as before, would remain as head of state, on a temporary basis to maintain the transition to a newer government. It was, to use terms commonly used by the Huabei diplomatic corps, 'dogshit'. It was a takeover, so often resembling palace coups, but if Melik-Aghamalian was still in charge, then in that case where he had come to power correctly, through legal means, and then therefore had aligned himself with the military to stay in power. I was of two minds of the issue. The first was that I was dismayed to see a mighty republic, and one I had learned so much from, brought low by such treachery, and the second was that this made ths status of our own republic more secure. I believe it was Tefere Abateid, the revolutionary and founder of the Anatolian Republic, who prayed, "When you send enemies against me, let them be in a fragile coalition."  This was not the last I would hear of the State Council to Preserve the Republic and Restore Order. I personally, found some news to be unexpectedly heartbreaking. Here I had once admired the capabilities of a great republic since I was a young man, and I still continue to respect their capabilities even as they opposed us, and now I did not know what to think now that they had fallen into a new and inglorious tyranny - I think of that officer droning out orders forever.  But to return to the war - the number of casualties over four years had now reached the two hundred thousands; a fraction of these from battle, over half from disease and desertion. In raw numbers, this was only a miniscule fraction of the population of both republics - but it was instead in the raw expense that this would bring to the state, and of the discontent of the popuations of our respective republics, who had rightfully grown sick of the war. Every so often, a new photograph - that novel device - would emerge out of an empty battlefield, or of the bodies a few soldiers grouped together, or of a field pockmarked by cannonfire, and the easy access to these images now means they are more easily embedded in the memory.  It was at this time that peace talks began in earnest. At the first round, the negotiators in my opposite party were quite peaceful - in loud clear voices and with fists on the table, they demanded extensive territorial cessions. To be more specific, all of Tibet's posessions in Hubei, with about one person in every ten of the Republic's population, and about one twelfth of all the republic's crops and manufactures. At this, I refused, being firm as my government so ordered. Even for peace talks, unless under a statement of complete duress, one does not accept the first offer.  These efforts were apparently vindicated - word soon reached Nanjing of a victory along the northern front - first denied, and then all over the major papers as each competed with the others for details. Lanzhou had been captured by Tibetan forces.  The war went on, now with movement - limited, but definite - along the northern half of the frontline.  The shift of forces along the northern front with the peace of the Anatolians had changed the calculus of the war, I thought. Perhaps more breakthroughs might come and so the entire North China Plain would not be open.  General He would soon advance further east. There was then, finally, after years of holding the line and retreat, some hope of a recovery. Those hopes were then immediately dashed.  Correspondence with instructions reached me from Lhasa. This was weeks out of date, and written in a secret code, or else some agent of the Huabei Federation read my mail. I was told, only in the most direct terms, that the government would push for any peace immediately, and that if the war went on soon, a total breakdown was possible. With this in mind, I went for the second round of negotiations with Chancellor Qi Shanlan herself. I felt sweaty and vaguely nauseous as I approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs office.  Most of the ministers I had spoken to claimed they were eager to be rid of the war. However, nothing would be approved without talking to Qi Shanlan, who had been chancellor these past 12 years and whose business was kept secret from me. In some cases, I had known only what the newspapers had written. It would only be after some weeks of haggling that I was able to get an appointment. I walked through the lined streets, under the shadow of the walls and the guards at their towers, nearly slipping on a patch of mud. It was only me and my translator, and I approached the fine lacquer table and carved furniture, I was not offered a seat. I only stood there, and Qi regarded me coldly. A porcelain spittoon was right next to her, as was her habit. I stood before her, as well as the assembled ministers, and began from my notes, speaking about the need to prevent further losses, with the suspension of hostilies and the prevention of prolonging the war. My translator finished this (I could understand multiple dialects, but I prefer to have a translator in times like this), and then she leaned over to her translator, who spoke concurrently. After I was done, she asked: "What the f--k did he just say? I didn't get any of that." "The Chancellor would like to know further details of your proposal," began the opposite translator. "Madame Chancellor," I began, "I am interested in hearing your proposals for an end to the war." Then she said, "What - he didn't have any ideas?" And the translators passed this along. The negotiation was already a complete muddle. Something needed to be done. Gathering my courage, I said: "We, the delegation for the Republic of Tibet, request a cease-fire for peace negotiations." At this, she only paused for a moment, then nodded to an assistant, who produced a document for a cease-fire already prepared and written, as well as enough ink for my personal seal.  The chancellor slid over the inkstone and brush with her hand. "Then sign." The negotiations for peace took place over the next few days and proceeded quickly. What was enough to make the counterparty give way, was an a complete acceptance of responsibility for starting the war to the Tibetan Republic and a ban on expansion or an enforced non-intervention for the next five years. This was a sign that the commitment to peace was more genuine, and therefore enough to prevent any major territorial transfers.  On February 8, 1846, the guns went silent. The orders went out by semaphor towers, horse and rider, and telegraph, and the armies were halted, and then they were to head home. Qi Shanlan was able to portray herself in speeches and in supportive newspapers as a successful defender against foreign invasion, and a hero of the republic who had prevented 'the dissolution of the republic and the evils of Tibetan expansion since the time of Lasya the Holy', to quote a prominent newspaper, although there were some factions within the government who believed she could have earned more in concessions, and who still were in a state of profound anger at foreign invasion. Some in Tibet were able to say that the war was brought into being to oppose the further expansion of the Huabei Federation, and that the war was not fought to subjugate another nation at all but to prevent the spread of Chinese encroachment, and that the peace was ultimately a victory. As for myself, I was recalled to the Tibetan Republic and then dismissed from office. A gentleman remarks: This war was concluded virtuously. [1]  The borders remained as they were, with Tibet still controlling Western Hubei, the Huabei Federation retaining control over Ningxia.  The Tibetan state budget, as far as could be determined, was burdened by war debts, largely from the price spikes of necessary goods, but nowhere near a risk of default.   Any new policies, to the extent that they were passed at all through the Red Mountain Party's grip on the legislature, were about reorganizing the state bureaucracy to prepare measures and learn more of the state for the next war, and the army, likewise, sought to apply some of its hardfought lessons in attacking entrenched positions and in setting up fortifiable positions.  Tibet would remain a great power, although one that had to yet again learn the painful lesson could not act with impunity as it would do four centuries before, and she would remain surrounded by many neighbors who are also regional powers, with their own agency, their own plans; it required allies, preparation, or reform if it wishes to survive. Yet in terms of public debate or in statements, there were many in positions of authority who were grown practiced in the refusal to admit mistakes. Any movement or reform was framed only in further progress, and the misstep of the war was alluded to only in oblique terms. While I was immediately removed from my position, my conversations with those friends who would still speak with me granted me the impression that business would continue as usual.  The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, from my conversations with remaining diplomats and the aristocrats who had retained senior positions, developed an interest in developing alliances with foreign powers, even granting an audience to those in especially remote places and to those where defensive alliances may seem like an overextension.  In the realm of domestic policy, the war had left a long shadow over the inadequacy and backwardness of large parts of the Tibetan Republic due to years of neglect from Lhasa. The low rate of literacy had long been decried since the days of the earliest republic as an impediment to liberty and the flourishing of every citizen; now it had become a matter of security, with conscripted soldiers unable to understand written orders. In response, the republic had to reinvent itself, completely: with universal compulsory education. This undertaking would be sponsored by the various monasteries that had retained their privileges and resources over the centuries. The monastic heads, seeing an opportunity, were keen to take on this responsibility, although they had additional backers from the industrialists and new rich, who asserted that educated citizenry was necessary to perform clerical tasks besides agricultural labor, and even the radical liberals and trades associations.  Yet, outside of the drawing rooms and gilded debating halls, there remained a deep well of discontent. Some kind of domestic reform would be well needed if the Red Mountain Party had the faintest hope of retaining its station.  The army leadership, eager to redeem its own reputation after the war as well as to prepare for the next, became involved in the process of public debate. Education would not just be a process of personal cultivation and self-improvement, dating back to the days of Laozi and the distant inspirations to our republicanism, nor would it just be a means of debate as the monastic scholars insisted upon. It would also be a process of drill, and of organizing thought.  To quote the famous speech from Sangiya Chautariya in a public forum on the matter: "If a nation has fallen by its own inadequacy into a state of total dependence on another, the way a vassal depends on their suzerain, then nothing it had done up to that point will be enough to bring it back up again from that state."  That is not to say, of course, that the bill did not have some substantial opposition. The doubts with the most merit were those raised by peoples educated in the traditions of other languages, and simultaneously did not wish to be instructed at monasteries, and who did not with to be taught only in the Tibetan language as it was spoken in Lhasa. It is one thing to teach some Tibetan in Nangqen or Golog wherever else how to write - but if some accommodation is not made, then what would stop these peoples from demanding further language education in their own systems, or perhaps their own state organization themselves? The same logic would apply.  Despite these complaints, however, the bill was passed easily, with only a minority in opposition - the state of education in the Republic had been neglected for too long, and only a sustained effort that had been not been seen since old National Alliance in the 1750s had begun their work in certain cities would be sufficient to continue it.  Yet the world did not stay still. The Anatolian State Council of whatever it decided to call itself this week, launched campaigns further abroad to shore up its own interests or goals.  The result of these costly affairs was establishing little villages and ports along the coast. Expansionism at this point may be considered a matter of 'national prestige', although not for any commercial gain, as such a port would be grievously expensive to maintain in the earlier stages.   In the way that steam rushes out of any faulty boiler and that every heated vapour expands to fill all available space, we cannot assume that every ambitious person would seek to remain still; nor could assume that the ambitions for the junta would remain limited within the territory that it had controlled at the start.  In the case of the Tibetan Republic, there was a growing need for reform - the watchword of the day. A clique of officers and scholars had proposed a radical restructuring of the bureaucracy, noting with disapproval that it had become the private domain of the aristocracy, who as before possessed the lion's share of educational opportunities or social ties necessary to pass the examinations or find a sinecure. Even the most incompetent and feckless son or daughter of a minor aristocrat could buy an officer's commission and therefore claim they had honorably served before marching an infantry regiment off to its certain death and then blaming someone else. Their aim was that officers would be appointed by political officials, instead of positions being de facto the property of various aristocratic families.  Yet such a campaign was opposed, with the legislature and bureaucracy all aligned in this case. Few in the legislature would dare vote themselves out of a job, or vote their patrons out of their privileged and comfortable positions. Any attempts to replace them were also ground to a halt, with examinations mysteriously delayed and applications disappearing.  A series of reform bills were defeated in rapid succession, and the effort was dropped unceremoniously, with the plateau aristocracy satisfied that their own interests protected, and that they had stopped 'those people' from 'climbing through the windows'. For now, the old poem is still true: While I do not have a son or daughter, but if I do, I would wish that they were a fool, that they may live a productive and peaceful life as a minister of the state. [2]  Soon it would be election time - the heads of industry, then major players in certain cities, particularly in Sichuan and along the Ganges, had organized their own political party, named for the Gold Mountains along the far north. Everything in this damned republic must be named after a mountain. Why not an animal, or something to describe their moral aims or stated goals? Mountains, I assume are visible enough that they are not mistaken for something else.  Though I still lived comfortably, far away from Lhasa, on my savings and in my own house, I could still readily tell something was wrong when the servants talked openly of how expensive food had become. I of course raised their salaries and insisted they take home leftovers from my own stores - it would be profoundly irresponsible of me if I did not - but this was a sign, seldom discussed by those in the gilded houses, that something was amiss.  Where inequity persists for too long, where conspiracy is allowed to fester or dysfunction allowed to continue, then all of the strata of society may become unstable or reactive, and with reaction to heat or shock, they may violently react.  Yet, to my astonishment, and perhaps shock, when I read the papers in 1848, the Red Mountain Party now held 3 out of every 5 seats in the great Kashag, instead of 2 out of every 3.  Perhaps the greatest sign of change was the inclusion of the tiny faction of the industrialists into the govering coalition, either as an incorporation of policy or preventing any further defection. A member of the legislature confided to me the reasons for this decision: "We can't bring the National Alliance back in, their ideas are too dangerous and destabilizing. It would be better off if we bring in the new money. The republic should best devote itself to making steel than writing manifestos."  Policy would therefore trend towards the priority of internal improvements. Factories would come up for every kind of manufacture. Many sponsored by private individuals or families, still others by state control or direction.  Additionally, new relationships with foreign powers must be cultivated, for the sake of our own security but also to make the prospect of a broader peace possible.  Great debates were the order of the day, even with the newspapers watched and closed on a frequent basis. But there will always be people who are willing to challenge the premises of the past, who would find some method of determining causation from the school of method or whatever else to challenge orthodox belief. Yet, we cannot assume that all debates are resuming the same way, nor do we now assume that history is purely cyclical, with two opposing parts - better to think of it as a spiral, where each debate builds upon the last, the solution of each debate becoming the premise for the next.  When I settled in Dhaka, I marvelled at how much the city had changed in the last few years - engine factories and steel factories not too far removed from those I had seen in Nanjing. On the railway voyage to Kolkata, one of my favorite cities to visit, I saw the grand houses of the educated and the propertied classes had grown larger, the servants had looked more prosperous and grown in number, and they walked with practiced ease among the new buildings and factories put up everywhere. And every so often, there was a rain of soot, like dirty snow.  To take a minor example of novelty: cans of food, stored and kept for longer times and longer distances, and soldered shut, had become a fad among the middle segments of society. I myself had ordered one out of curiosity and then spent far too long trying to open it with my knife. If such a thing had been produced in large quantities for the last war, one may imagine the cost of feeding then would be less of a catastrophe.  Of course, all these reforms meant an increase in spending. While the complaints were from modern theorists that the republic must keep a rein on its expenditures; a government as large and as established is no household that has to make its bills and budget for for its food and cloth. Lending can continue for far longer. The question is for how long. But now that 'reform' was truly underway, or at least in a sufficient state of progress, the leadership of the Red Mountain Party, as near as can be determined from my investigations and from my examination of public statements and documents, also believed it necessary to expand, as did Anatolia, and where it had failed against Wu.  That, in this case, resulted in the turn towards the southeast. Other authors that I will not name would contend that this new campaign was a 'distraction' from the issues of the day - of high prices, or of poverty. I must contest that description. Warfare on a large scale is too expensive to be only a distraction. This campaign was an attempt to secure resources, enrich the treasury, and to provide what was percieved to be a more stable defensive frontier. Champa had already ceded treaty ports to Egypt and Anatolia, so that might be percieved as encroachment. Majapahit was a great power and had the strongest navy on earth. Hsipaw, by process of elimination, would be the target. For centuries, before and after the Tibetan Empire first expanded to the southeast, the region was ruled by local chiefdoms, independent city-states, or other rulers. With the retreat and eventual dissolution of the empire in the past century, Hsipaw was the greatest of these Shan States to emerge. It, like its predecessors, was ruled by Saophas, or local kings - it was insular, had no allies willing to defend it, and it had practiced the widely loathed practice of debt slavery - so the overthrow of an unloved kingdom was seen as a moral benefit.  I knew the Hsipaw ambassador to our Republic. He had passed along messages between us and Majapahit on some occasions, and I had attended the meeting where the war was to begin. We exchanged greetings, and then our ambassador handed him a note, which emphasized the sudden break of all relations between our two countries a declaration of a state of war. "A war? But why?" He said, his voice shaking. The ambassador read out his instructions as well as the full text of the note. After this, he said he understood, but then he started to cry. I poured him a glass of water.  Now, as the armies moved to the border, the military and foreign service grew keenly aware of the risk of foreign interference. They had staked much on the assumption that the Huabei Federation had little interest in the region. However, the Majapahit were another story, and a few messages were sent, keenly aware of the need to avoid offense.   Yet, to the relief of Lhasa, Majapahit had little interest in 'the continent'. The empress Jayaa's focus was further east, to settlements and ports on such distant islands as Mala, and expanding the reach of their navy and therefore the empire further. In a discussion with the Majapahit ambassador to our court, we raised some of the topics. It is not as if we are so gauche as to start by asking permission. But she was reading something about tariff schedules and waved away our concerns and asked: 'Why is that any of my business?' and that was enough of a response for us. So in that manner, the armies of Tibet marched further south, not even with the reserves drawn up.  The Saopha had made the mistake of a pitched engagement against a larger army. There is little need to belabor the narrative by excessive description. By the start of 1852, within a few months, it was all over.  A letter from my friend T---------, an officer from a sanskari[3] family who led a detachment of infantry on that campaign, went as follows: "About a week's march out of Chiang Rai, our company had stopped to visit a village off the road and to inform them that the saopha was deposed and that they were now citizens of a republic. The locals didn't know who or what a saopha was, much less anything about the kingdom they were nominally a part of. Furthermore, they had no interest in what a republic was, having been informed that they already elected their own village mayor anyway, but they were at least quite happy to swap silver coinage for supplies, although they did ask about the new writing on each coin." How obsessive is the process of establishing control! Are we so far removed from Gyalyum the Benevolent almost a thousand years before, who would take her entire court with her as she fought on the mountainside, that they might not stray too far from her grasp? The Tibetan Republic had now reached as far south as the towns of Taunggyi and Chiang Mai, and now had a more advantageous position in the area; a longer border with Champa; and if Majapahit were offended, it was not enough to cause immediate action.  The areas now administered had the burden of being some of the most impoverished parts of the republic, with peasant smallholders and subsistence farming widepsread, but maybe with such valuable commodites as lead, teak, or opium, perhaps the flow of commerce may head to the region instead of moving around it. With that business done, the debates of the central government ebbed and flowed; new topics were brought up and were set aside as opinions changed, factions formed and fought, papers and favors changed hands.  The war was concluded, and Tibet saw its position marginally improved. Yet still it faced a slowly creeping deficit and slow growth as well as the growing risk of discontent, which was seldom understood or addrsesed by those in the Red Mountain Party corners. There were perhaps some stories of warehouses burned or windows broken, but these were attributed to interference, to conspiracy, or to a lack of trust in an established order.  But eventually, and not unexpectedly, there was an organized response - relief for the poor. Poverty relief had only been the domain of individual monastic complexes or possibly individual charity. The empire had left behind no legal bedrock for charity (save Gyalyum the Benevolent passing out gold dust, or Lasya the Holy either promising pillage from conquests or beheading indigents). Now, after a few experiments with charity in the early years of the republic, momentum had built up for a more organized method of relief.  Such a law, of course, would face resistance from the expected factions. The prominent landowners of the plateau aristocracy would be first among these. They still belived that poverty was caused by moral failure, in this or a previous life - and that it was neither the responsibility or the capability of the government to go on about the indigence or immorality of the very poor. The supporters of the law were a strange coalition. On the one hand, industrialists, who proposed a system of 'workhouses' as a centralized means of providing charity or relief, and - the radical liberals and trade unions who so often opposed those industrialists. These groups cited the newest tracts in the social sciences, noting that industrialists tended to push wages down as far as possible in order to maximize profit. By contrast, the Gold Mountain party was tempted to go over to the law, noting the growing problems of rural poverty, and the hypothesis of accelerating population growth and urban unemployment, and that some form of employment would be a moral good in itself.  Such a law, of course, had met stringent opposition nearly from the beginning.  For a loud and growing element of the conservatives, poverty relief was the wrong way to go about it - and certain elements within the plateau aristocracy itself saw the need for a more dramatic return - to reintroduce social hierarchy, to impose new restrictions on the non-nobility.  I had the chance to meet with one of these new figures, a Mr. Namgang Wangyal, or at least to attend one of his speeches, given to a salon of the aristocracy after a dinner party. He was a young man, clean shaven, in simple unadorned clothing, less of the types that we see every now and then talking on the street corners. He spoke at first with calming images and a low tone, of a longing for a Tibet of the distant past, of avoiding the steady compromises of the later Republic. He was colder when he spoke of the end of the unnecessary compromise, of purity, of 'stopping them from trying to climb in the windows'. There was only a cold void behind his eyes. I felt only a scream from my gut, in the middle of the polite applause, that this one was not to be trusted.  We can't just sip from our crystal glasses all day and pretend that everything will be stable forever, now can we? The agitators of the present day are ultimately a dangerous force.  Certainly, the Red Mountain Party would attempt to co-opt such rhetoric and use it for its own means; an authority justifying its continual hold on power by whichever means is most expedient.  But the trains are still coming.  The negotiations for poverty relief continued apace. The coaliation appeared fragile, and then, with new developments, there was a risk of this law going the same way as bureaucratic reform. Representatives of the Gold Mountain Party, in private conversations with me as well as in public statements, still feared the risk of granting too much to 'the idle poor', which they had decried in the strongest terms as a moral failing.  Yet as if in response, cracks in the stone facade of the opposite Red Mountain Party had made themselves known in the election of 1852. Having first won two out of every three voters, now they had slid down to just over half. The Gold Mountain Party had to be kept happy for them to stay in with the rest of the coalition. A democracy, one that lasts, is one where parties can peacefully lose.  The Tibetan Republic was still a large but if one looked at the average citizen, then there was still a vast group of the desperately poor. Millions went on and lived in the same way that they had lived for centuries before.  But with a prolonged peace, there was at least the possibility of improvement. Soon there would result a quiet toleration with Huabei, which one hopes may yet last. Trade routes emerged over some of more valuable resources, or at least those that were valuable enough to make the trip profitable - though not always manufactured goods, of which there was already an established market. And as for armaments being sold to Huabei - well as far as I can tell that has not yet happened again on a large scale.  The Tibetan Republic could continue to build up a coalition of its neighbors - whether monarchies that survived the collapse of the old Tibetan Empire or other republics. This collegiality with its neighbors would serve for the near future as a defense against other opportunist neighbors.  There then emerged a slow, uneven, belabored, yet possible march of progress, of ideals prorgressing. For the first time ever in the history of Tibet, one person in every four could read and write.  Slowly, a new manner of state was being built, with new responsibilities and new functions. The republic would run its own bank, and no longer solely rely on outside creditors.  Dhaka and Kolkata, great cities of their own, so vast that I could walk through them for an entire day and still not reach the countryside, became centers of steam-boilers, iron wheels, cranks, pipes, furnaces. It would be possible to spend an entire day in the company of the plateau aristocracy or those captains of industry and never see for a day the factories. And yet without seeing green foam, like algal blooms, rushed out of pipes.  The question of poverty had then changed again, dramatically from its original concept. Due to the push from Mr. Wangyal and his cabal, poverty relief would take on a much more paternalistic and moralizing character - with the separation of families, or enforcement of routines, or of a way to promote 'traditional discipline', citing old monastic regulations from centuries past. As if a sundial would be turned again or the gears of a mechanical clock wound back.  Poor houses were enacted, as was the schema of forced employment for wages - and then, the law hit another problem - putting the law into practice.  The scale of poverty and the number of people that would have to be found, transported, and employed, had been far beyond even the worst estimates as proposed by the relevant ministries; and the budget of the Republic, far encumbered by tax evasion, an inadequate bureaucracy, was soon in the same financial situation as conscription and a war against Huabei Federation. It would soon be argued that the program would have to be scaled back or repealed, should the state be able to maintain even the most basic functions. Poorer people were quite understandably suspicious of the law - comparing it to being abducted into slavery; and in seeing this as an unconscionable assault on the lives of their fellows, and would ambush the enforcing officer or refuse to follow his dictates or summons.  It was in this state, possessed of plenty yet shackled by the depths of poverty, claiming immense ambition yet shambling forward with hands forward like a man cast in the dark. That was the state of how Tibetan Republic found itself in the start of the year 1853. THE WORLD: 1853  ========================================= Footnote 1: This is a stylistic reference to the Zuozhuan Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals, where historical anecdotes were described in terse, succinct language and then summarized according to their moral lessons. Footnote 2: A quotation from Su Dongpo. Footnote 3: A loanword from modern Hindi; cultured, well-educated. Kangxi fucked around with this message at 16:21 on Oct 28, 2023 |

|

|

|

A good bit of peace to grab, if you can take it! Hopefully the poor laws can get reversed soon, that's quite the ballooning expense on a large nation like tibet

|

|

|

|

Also, something funny that didn't make it to the post: the AI built a bunch of food factories in Tianshan, a desert province with a low population

|

|

|

|

The only reason it didn't build a clipper factroy is the lack of docks, but the AI surely tried.

|

|

|

|

Kangxi posted:

you laugh, but the canned beef for horses trade is the wave of the future!

|

|

|

|

every time tibet expands i think of mr creosote being asked if he wants a wafer thin mint

|

|

|

|

That was a less harsh peace than expected. Also, running a deficit is not a bad thing if you can keep expanding your economy to match.

|

|

|

|

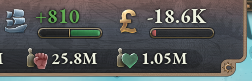

Looking forward to the chapter written from inside the inevitable level 400 art academy with 1% employment.idhrendur posted:That was a less harsh peace than expected. Also, running a deficit is not a bad thing if you can keep expanding your economy to match. The 18k deficit is whatever, the 60k deficit is another matter.

|

|

|

|

I think it's a front for some illegal trading shenanigans on the border. The factories look profitable to me.idhrendur posted:That was a less harsh peace than expected. Also, running a deficit is not a bad thing if you can keep expanding your economy to match. I'm not the best Vicky player, but at this point I would be very worried. Interest will start piling up quickly.

|

|

|

|

Tulip posted:The 18k deficit is whatever, the 60k deficit is another matter. Chatrapati posted:I'm not the best Vicky player, but at this point I would be very worried. Interest will start piling up quickly. It's been a while since I've played Vic3, my sense of scale is distorted.

|

|

|

|

If nothing else, that 60k deficit is in the red, meaning that even if Tibet stopped constructing stuff they would still be losing money. That is never a good situation, even if you're that far from the credit limit. Also, yay Angaland! Never thought I'd be cheering for the English in a megacampaign and yet here we are.

|

|

|

|

idhrendur posted:It's been a while since I've played Vic3, my sense of scale is distorted. Hellioning posted:If nothing else, that 60k deficit is in the red, meaning that even if Tibet stopped constructing stuff they would still be losing money. That is never a good situation, even if you're that far from the credit limit. The red was a tell, but there's also not really one singular sense of scale in V3. An 18k deficit can be perfectly manageable. I've had 100K+ deficits be perfectly manageable. I've also triggered death spirals with 1k deficits. The actual thing that matters is the ratio of deficit to growth, specifically the growth of your maximum credit. From the screenshots we saw we didn't see the debt meter filling up so that means the deficit is more or less balanced with the growth of credit, so, balanced. And this is me going a little more into victoria gameplay theory but there's two pieces of common wisdom players have about V3 management that I think are worth breaking with pretty frequently, which are avoiding civil wars and avoiding bankruptcies. I've absolutely had games go very well where I drove my country into bankruptcy as part of a crash industrialization, and deliberate early game civil wars are honestly often a great idea. Of particular note, Qing is the #1 most commonly played nation in V3 and Qing civil wars are frequently cheaper than the costs of avoiding those civil wars. And this is a pre-1.5 piece of advice so grain of salt since that's coming out momentarily, but if you are trying to do a civil war slingshot its worth doing those early because arguably the worst effect of a civil war is that the revolters frequently tear down every single loving university they control and that's a LOT of construction waste. That might have changed in 1.5, I haven't been in the beta. I'd probably not recommend a civil war if you started with this TL's Tibet FWIW, the 1836 law set is really good. Traditionalism is really the law that's so bad that it can distort your first 20+ years of gameplay and worth fighting one (or more!) civil wars over.

|

|

|

|

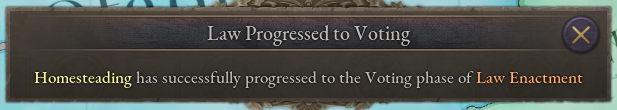

my post was eaten by a probe, but the main thing about that deficit too is that you can grow an -18k from construction into something more manageable fairly quick, esp at the scale tibet is. The problem with this deficit is that there's a couple extra hidden costs to it. Mainly that it eats up and produces more bureaucracy costs, which either hit tax efficiency or your govt spending line and will keep going up as long as the institution exists at some rate. Second is the social spending line item itself will also grow with population/poor pops. So instead of being a growth-positive deficit it's got several extra stacking costs on top of interest rate increases, all of which combined can easily start one into a death spiral or at least really stagnate the actual growth you care about e. and yeah there's scenarios where you want to game civil wars optimally (oftentimes its acceptable but also lots of clicking/busywork sooo) and more niche ones where you can gently caress with default/bankruptcy poo poo, but neither really apply with a fairly progressive and ahead-of-pack tibet iirc ThatBasqueGuy fucked around with this message at 00:43 on Oct 30, 2023 |

|

|

|

Also, it may have been missed, but it needs to be emphasized. The heroine has appeared in Europa.

|

|

|

|

Tibet!World gets the good Victoria Also, excellent update as always!

|

|

|

|

"Lasya the Holy either promising pillage from conquests or beheading indigents" She was the best.

|

|

|

|

Pacho posted:Tibet!World gets the good Victoria Just because I think its funny, here's a picture of Queen Victoria's mourning dress with museum staff for scale

|

|

|

|

Pocket sized queen.

|

|

|

|

Some news: It looks more and more unlikely I'll be able to update the save to 1.5 as I did to 1.4; so it looks like I'll add a few mods such as Anbeeld's AI mod to keep things going.

|

|

|

|