|

Moving this derail out of the Libertarian thread.Helsing posted:I confess I'm not overly familiar with the internal situation in Chile but it is well documented that the US government immediately terminated most of its foreign aid and Kissinger famously gave the order to "make the Chilean economy scream". I dunno whether Kissinger ever spoke that line. For the rest we can go to the tape and look at documents archived by the State department. Editorial note in Doc 148 posted:In addition to the expropriation by the Government of Peru of the assets of the International Petroleum Company, U.S. officials were faced with the prospect of expropriation of U.S. private copper companies operating in Chile. In a May 4, 1969, letter to President Nixon, President Eduardo Frei of Chile wrote that he would soon present an austere economic program for Chile to try to control inflation and revive a depressed agriculture resulting from a severe drought the previous year. While expressing his desire for continued good relations with the United States, he warned: "To present this plan and to exclude from these sacrifices the copper producing companies is politically and morally impossible." (National Archives, RG 59, S/S Files: Lot 72 D 320, Chile: Frei to Nixon) President Frei informed the U.S. Ambassador in Santiago, Edward M. Korry, that he had to make changes in two areas of the 1967 agreements which would affect two U.S. companies, Kennecott and Anaconda: link the tax rate to the price of copper instead of a 53-54 percent rate regardless of the price, and "Chileanize" Anaconda, which was still entirely U.S.-owned, either by getting Anaconda to sell some of its stock to Chile or, if necessary, by expropriation. (Memorandum from Kissinger to President Nixon, May 6; National Archives, Nixon Presidential Materials, NSC Files, Country Files-Latin America, Chile, Volume I 1969, Box 773) Because Kennecott was already 51 percent-owned by the Government of Chile, it was not a candidate for expropriation. What is well documented is that, in response to the Allende government expropriating American businesses without compensation, the Nixon administration considered a range of measures that would have put pressure on Allende to stop expropriating U.S. businesses or to pay compensation. Ultimately Nixon did not cut off money and the aid situation more or less fell out like this. Wikipedia: United States intervention in Chile posted:The U.S. provided humanitarian aid to Chile in addition to forgiving old loans valued at $200 million from 1971-2. The U.S. did not invoke the Hickenlooper Amendment which would have required an immediate cut-off of U.S. aid due to Allende's nationalizations. Allende also received new sources of credit that was valued between $600 million and $950 million in 1972 and $547 million by June 1973. The International Monetary Fund also loaned $100 million to Chile during the Allende years. Helsing posted:This was on top of the extensive internal opposition to Allende such as those highly disruptive transportation strikes. Yes. In response to drivers having their trucks seized and other measures like that. Helsing posted:You're accusing other posters of being ignorant or simplistic Yes. Helsing posted:but it seems like you're doing the same thing declaring Allende's policies outright failures. No. Helsing posted:He was only in power for three years, inherited a polarized and unstable country, and faced extensive economic sabatoge from both the world's most powerful country and some of Chile's internal actors. It's important to know the history, dude. =( Chile was not in a great place when Allende took power but his administration was basically a study in how to knock a country off its rails in the fewest possible steps. The administration didn't need any help from Nixon. I posted a link to an economic reading of Chilean history in the other thread that I'll include here: Economic Reforms in Chile: From Dictatorship to Democracy. Helsing posted:Also correct me if I'm wrong but my understanding is that one Allende era reform that Pinochet never reversed was the nationalization of the copper industry - and copper exports were a huge source of national income and government revenue throughout the Pinochet era. That was one of the better measures, yeah. The nationalization of copper began under Frei, who "negotiated" the government into a bunch of joint ventures giving it about a 50% stake. Allende came to power and basically told the private partners "gently caress you, we're taking it all and we're not paying". I think nationalization was the right call but seizure without compensation wasn't the way to do it. That poo poo more than any influence from Washington made it harder for Chile to get international financing. Also, I guess this can be the Chile thread? ITT let's talk about Chile and current events in Chile. There's a lot going on. Tax and education reforms are big topics. There's always someone striking somewhere. Lots to gab about.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 25, 2024 06:21 |

|

Reserved.

|

|

|

|

Do you have any contact with people who experienced repression or lost family members under the Pinochet regime?

|

|

|

|

SedanChair posted:Do you have any contact with people who experienced repression or lost family members under the Pinochet regime? I'm happy to answer questions about the period or stuff that's going on now or life in general, but I don't want to talk about my personal situation and acquaintances because Internet. Yes, I know people. I would say that's not super common but it's not rare either.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Moving this derail out of the Libertarian thread. From the Excerpt you posted (I only saw the one) it doesn't really detail what exactly he did wrong, and seems to be more about external factors that undermined him pretty hard. I mean he was accused of being a "dictator" but none of that is substantiated in the excerpt posted. Anyway, since he was only in power for three years its really impossbile to judge Allende's policies. Its just to short of a window for anything to really happen. Not to mention most of it undone by his successor. If you really want a to compare him to big P, well you can't. He nationalized the copper mines, and Big P murdered a poo poo ton of people. There is no way Big P comes out even close. CharlestheHammer fucked around with this message at 00:25 on Jul 25, 2014 |

|

|

|

This is going to be a poo poo show, but I'm excited to learn more about how Pinochet was simply a product of his times and Allende was a horrible illegal socialist who doomed the country.

|

|

|

|

Ok I've got an honest question with you being kind of center-right what do you think is wrong with Chile at the moment and how would you fix it?

|

|

|

|

rear end in a top hat anarchists have been blowing up bombs here the past week

|

|

|

|

I don't see how Pinochet Chile would be the exception rather than the rule for corrupt banana republics and lovely South/Latin American CIA honeypots, nor should anyone seriously expect anyone believe that Pinochet was anyway directly responsible for anything other than the disappearance of some 30,000 people and a sharp drop in literacy rates due to voucher reforms.

|

|

|

|

This whole topic really makes me want to re-read all my Project Cybersyn stuff, particularly~Cybernetic Revolutionaries, although it is somewhat didactic. I believe I first heard about it on these forums. It was misunderstood as a way of centrally managing the economy from Santiago, but really the purpose was to facilitate better working of the economy in a kind of biological structure, where the head office would only deal with emergencies that can't be handled at lower levels. Unfortunately, its implementation was doomed because for it to work you had to have buy-in all the way from the factory worker up to senior management, and class antagonism even between workers and the engineers training them in the factory-level equipment was just too large. The one real achievement (at least as far as the Allende administration is concerned) of the program was the use of Telex machines to alleviate the effects of the 1972 transport strike. (The wikipedia description fails to mention these facts, but they do appear in Cybernetic Revolutionaries, and I think in Beer's account in his Brain of the Firm, one of the main books in which he proposed his Viable System Model for business/government/social distributed regulation and control.) The story of Project Cybersyn is very interesting in how it interacts with what the UP were trying to do, and how the failure reflects problems with implementing computational solutions to social problems. A book about a similar attempt in the Soviet Union under Khruschev is From Newspeak to Cyberspeak, again, recommended on these forums. A more whimsical account can be found in Red Plenty, a fairy tale with citations and notes of more or less the same era.

|

|

|

|

SirKibbles posted:Ok I've got an honest question with you being kind of center-right what do you think is wrong with Chile at the moment and how would you fix it? That's a really broad question. Chile has a lot of challenges to overcome and they're related. Probably the biggest thing is that the economy depends heavily on exporting copper and other minerals. To give you some idea, Chile's GDP in dollars in 2013 was around 300 billion. Exports were about 80 billion and copper was half of that. Mining directly employs only like 70,000 people but indirectly a great many jobs in Chile depend on the flow of money and economic activity it generates, and the health of the mining sector is one of the big variables that determines the peso / dollar exchange rate (the others are the prime interest rate in Chile, the prime interest rate in the U.S., and on some level what's going on in Chilean politics at the moment). Over the long run that's an unstable situation because a shift in trade patterns or a prolonged global slump will spike unemployment, send the exchange rate through the roof, spur inflation (because so much is imported, and the peso will be weaker) and depress government revenue. Basically what I'm saying is that without strong mining performance there is no money. The solution to that is to open up new export markets, probably in services and finance, leveraging Chile's relatively stable and well functioning (by Latin American standards anyway) business environment. Also developing the internal economy, though as a country of just 17 million people there is limited potential in that. That means educating a bunch of bright young people who can go out and build those things, which would be great except... Chile's education system is pretty bad. In the OECD's program for international student assessment 2009 Chile ranked 44th in reading, 49th in math, and 44th in science. That's in terms of higher education outcomes. This article describes the structure of the Chilean education system. In practice there are a few good universities (by Chilean standards. Some are private and some are public. There are a lot of additional private institutions that sprung up quickly to serve poorer and lesser achieving students that are "accredited" but are basically degree mills that grant worthless credentials while saddling students with debt. Students would like to go to the good universities, however admission is competitive and also very classist and there are nowhere near enough slots at those institutions for everyone who wants to go. Nor do many Chileans get primary and secondary education adequate to make use of those opportunities even if they were there. If I knew how to fix this I would probably be Education minister. =( Education reform is probably the biggest challenge and public preoccupation facing Chile today*, and is a catalyst for a lot of public dialogue and civil unrest. There have been several waves of protests and school occupations by students. Again, here's an article with some background. English language reporting about this is almost universally awful. Sorry for a bunch of wikipedia links. It's hard to find english language sources covering Chilean affairs in a neutral way. edit: *Unless you're a Mapuche. Then you're probably more worried about getting strung up by nervous farmers because your bros have been attacking land owners. wateroverfire fucked around with this message at 16:04 on Jul 25, 2014 |

|

|

|

Absurd Alhazred posted:This whole topic really makes me want to re-read all my Project Cybersyn stuff, particularly~Cybernetic Revolutionaries, although it is somewhat didactic. I believe I first heard about it on these forums. Cybersyn was doomed because in order to be embraced by the Chilean bureaucracy every step of every calculation would have to be printed out in triplicate, taken by hand to the ministry to be stamped/validated, then returned by hand to the appropriate official's desk where it would sit for weeks before being punted to the next official in the process. =(

|

|

|

|

King Metal posted:rear end in a top hat anarchists have been blowing up bombs here the past week Nobody taking credit so far. Kind of amateur hour for political violence. If no one knows who you are what's the point?

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Cybersyn was doomed because in order to be embraced by the Chilean bureaucracy every step of every calculation would have to be printed out in triplicate, taken by hand to the ministry to be stamped/validated, then returned by hand to the appropriate official's desk where it would sit for weeks before being punted to the next official in the process. =(

|

|

|

|

I guess this is the appropriate thread to ask in, does anyone have any context for that Latuff cartoon about the president of Chile getting hosed in the rear end by Goku? It's absolutely hilarious, don't get me wrong, but I have no clue what it's referring to and it bugs me.

|

|

|

|

|

Absurd Alhazred posted:Those don't seem to be the obstacles that the project actually encountered, at least according to Beer himself or to Medina in her research on the topic. The project had a lot of official support going quite a ways through the government, being backed by Allende himself and by CORFO. Do you have any evidence to the contrary? Medina in particular seemed to have gotten information from a large variety of sources, including Fernando Flores, who is more of a centrist business-type Senator now, if I'm not mistaken. It was just a cynical comment based on my frustration dealing with Chilean bureaucracy. =) More seriously, I think you would have a hard time implementing a Cybrsyn-like system in Chile even today. It's hard enough to find workers who have had exposure to and feel comfortable using database products like simple ERP systems. I can't imagine what it would have been like in the early 70's. That's separate from the mathematical intractability of the modeling problems. This came up a couple of times, I think, in the Marxism thread when some of the economists who post occasionally in D&D got involved.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:It was just a cynical comment based on my frustration dealing with Chilean bureaucracy. =) quote:More seriously, I think you would have a hard time implementing a Cybrsyn-like system in Chile even today. It's hard enough to find workers who have had exposure to and feel comfortable using database products like simple ERP systems. I can't imagine what it would have been like in the early 70's. That's separate from the mathematical intractability of the modeling problems. This came up a couple of times, I think, in the Marxism thread when some of the economists who post occasionally in D&D got involved. Well, the idea was that workers wouldn't need to learn anything complicated. I think it came down to basically "upvoting" or "downvoting" how they were doing, dealing with whatever they could themselves, and it only involving people higher in the hierarchy if things went horribly wrong; and each level at the hierarchy had a mostly tractable problem at their scale. It was tractable because the effort was distributed and recursive, and the idea wasn't to be optimal, just to respond better than without the right communications. On some level, he was trying to simply mirror and improve existing hierarchical structure that he'd found in the British military, and a variety of businesses as an operations researcher. I'm not going to lie, while cybernetics is really interesting for me, and I've read a lot about its history, and while I do have a background in computer science, I have not really researched this topic enough, other than to know that the whole "perfect market" thing is rubbish. But approximating NP-hard problems with polynomial-complexity algorithms is a an active field of research, and you don't really need to have an exact solution to have something that works better than the status quo. Beer's specific solution may or may not have worked; but with all of these issues, it seems to me that questions of politics, power, and cultural inertia come in much earlier than any kind of computational limit. Anyway, beyond my particular fixation, you mentioned repeatedly that there is a dearth of good coverage in English. If you are up to it, I would personally appreciate rough translations if you think they would enlighten us. I can probably give rough translations of short pieces in French, if there is any such you could recommend, but I imagine Spanish-literate posters would be more relevant generally.

|

|

|

|

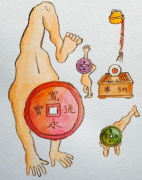

SALT CURES HAM posted:I guess this is the appropriate thread to ask in, does anyone have any context for that Latuff cartoon about the president of Chile getting hosed in the rear end by Goku? It's absolutely hilarious, don't get me wrong, but I have no clue what it's referring to and it bugs me. Here's the image for anyone who hasn't seen it.  Here's what Latuf said about it here (translation by Andrés Chandía). quote:I spent the last 3 weeks in Chile participating of protests against building of a dam in Patagonia by Hidroaysén, students for public education, against anti-terror laws applied to Mapuche. During these demonstrations, it was pretty common to see protesters on the streets chanting "Goku Goku, Super Sayayin, culeate a Piñera por el chiquitin!", something like "Goku Goku, Super Sayayin (Famous Japanese comics character), go gently caress Piñera (Chile's president) in the rear end". Based upon this chant, here's Goku and Piñera, together, in a cartoon. Reproduction is free for everyone! ...That doesn't answer the obvious follow-up but there it is! Absurd Alhazred posted:Wait, so you're saying that this is post-Pinochet bureaucracy? Oh my, yes. Chile is a very bureaucratic place and that expresses itself in some ridiculous ways sometimes. For instance, the following happened to someone I know: =) I'm applying for my driver's license. Here's my paperwork! =) My country doesn't give 8th grade diplomas but there's my university degree so now that's settled we  But.. But..A driver's license was not gotten that day. Absurd Alhazred posted:Anyway, beyond my particular fixation, you mentioned repeatedly that there is a dearth of good coverage in English. If you are up to it, I would personally appreciate rough translations if you think they would enlighten us. I can probably give rough translations of short pieces in French, if there is any such you could recommend, but I imagine Spanish-literate posters would be more relevant generally. I don't know good french sources. When I come across interesting spanish sources I can link them and do some translating or at least paraphrasing. Are there topics you're in particular interested in?

|

|

|

|

drat now I want to read about "cybernetics". I heard references to cybernetics reading about the soviet union but I was always like "they wanted to make cyborg super-soldier bureaucrats to run things????"

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Oh my, yes. Chile is a very bureaucratic place and that expresses itself in some ridiculous ways sometimes. For instance, the following happened to someone I know:  quote:I don't know good french sources. When I come across interesting spanish sources I can link them and do some translating or at least paraphrasing. Are there topics you're in particular interested in? What do you think about Michelle Bachelet? Any good critiques of her current plans? Baronjutter posted:drat now I want to read about "cybernetics". I heard references to cybernetics reading about the soviet union but I was always like "they wanted to make cyborg super-soldier bureaucrats to run things????" It's been a while since I read it, but the ideas went like this: we want a planned economy, so we should use computer science/cybernetics/algorithms to plan it, hey hold on if we use linear optimization we find that we get "prices" like in capitalism, meaning it doesn't have to be centralized after all, then people get spooked, especially after Khrushchev gets deposed, and to it in a centralized manner anyway, but with paperwork and getting nowhere. Did that make sense? Probably better for another thread and for someone more knowledgeable than me, frankly. Anyway, it's the history of those kinds of plans which make me so wary of Marblebux, and other Eripsa software solutions to human problems. Absurd Alhazred fucked around with this message at 21:37 on Jul 25, 2014 |

|

|

|

Absurd Alhazred posted:What do you think about Michelle Bachelet? Any good critiques of her current plans? She's doing a lot to make the system more equal (raising taxes, education reform, indigenous rights), but many of those who voted for her are saying she needs to move faster. The big deal right now is making education free at all levels and reforming the constitution (or just straight up rewriting it). A lot of my Chilean friends thought she wouldn't have the balls to call a Constitutional Assembly, so we'll see if that happens. Here's an article in English on her first 100 days and here's one about education reform. She says her goal is free education for all by 2020.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Moving this derail out of the Libertarian thread. It was Nixon who spoke that line: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/nsaebb8i.htm quote:

The idea that intervention came as a response to Allende expropriating American businesses is bullshit, and disproved so conclusively that I cannot really understand how anyone would still say that crap today in good faith. Let's go step by step: intervention started in 1962 with a group dedicated to helping ensure that Frei would win the 1964 elections: https://www.cia.gov/library/reports/general-reports-1/chile/#4 Note that it is from CIA's own website. Then, in the elections that Allende eventually won, the US spent more money to defeat him on per capita terms than both US candidates combined in the 1968 US elections. After Allende won, the US ambassador to Chile started plotting ways to block Allende from taking power: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc18.pdf The make the economy scream line came from a September 15th, 1970 meeting: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc26.pdf Where the US decided how they were going to essentially disrupt the Chilean economy in every way possible. It also shows the US plotting a coup that early. Then, as early as October 18th, 1970 the US started planning a way to fake a coup attempt by Allende so that their own coup would be justified: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc27.pdf And then as early as December 4th, 1970, with Allende in power for a month, the US had a de facto economic blockade against Chile: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc20.pdf quote:

This is, again, not true. Originally the strike was about freight rates and difficulties in obtaining parts. As a result of the strikes the government seized some trucks. As with most other economic phenomenon, it later came out that the trucking strike was financed by the CIA: http://static.history.state.gov/frus/frus1969-76v21/pdf/frus1969-76v21.pdf (page 867, for example) quote:

The idea that it "didn't need any help from Nixon" is false. As seen above, with evidence only from declassified US documents. quote:That was one of the better measures, yeah. The nationalization of copper began under Frei, who "negotiated" the government into a bunch of joint ventures giving it about a 50% stake. Allende came to power and basically told the private partners "gently caress you, we're taking it all and we're not paying". I think nationalization was the right call but seizure without compensation wasn't the way to do it. That poo poo more than any influence from Washington made it harder for Chile to get international financing. Once again, not true. First, the third stage of the nationalization of the copper industry passed congress by a unanimous vote, so it is misleading to say it was Allende who did anything. Second, Allende's government did pay for some of the copper companies that were nationalized. The reason most were not compensated and others received less compensation than they wanted was because the UP's government decided to deduct stuff like machinery that was turned over defectively, book value of unexplored mineral deposits that was included in the company's valuations, debts to the state, and previous payments by the state to the company: http://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1985&context=vlr (see top of page 34 of pdf) Not to mention that as controversial as you may feel those nationalizations were, not even Pinochet reversed them or changed anything related to compensation. Now, as far as original contributions go, here's one thing that generally doesn't get the attention it should: La Cuestion del Plebiscito Even with all the evidence above you will still hear the eventual person defending Pinochet and the coup because "communism!" The part that is not told is about the plebiscite Allende was about to call. http://books.google.com/books?id=cB...%201973&f=false Allende had a speech set for September 10th, 1973 where he would have called a plebiscite on whether he should remain president because he saw the risk of a coup and wanted to avoid a bloodbath. He delayed the speech because they were in talks with the PDC to see if they would accept the plebiscite as a solution. Then Allende was extra naive and alerted the military commanders that he would announce the plebiscite on September 11th at noon. So the military commanders pushed up the coup to September 11th, 6 am. In other words, the coup was pushed up because Allende was about to announce that the population would get to vote on whether he would finish his term. And that wasn't even done in the hopes that he would win the plebiscite. But the coup was pushed up because even if Allende had lost, Unidad Popular would still have a significant presence in both houses of parliament (UP actually won seats in the 1973 election in comparison to 1969).

|

|

|

|

joepinetree posted:The idea that intervention came as a response to Allende expropriating American businesses is bullshit, and disproved so conclusively that I cannot really understand how anyone would still say that crap today in good faith. Wait wait slow down, as a highly educated american socialist sympathizer, I want to say that expropriating american businesses in Chile kicks rear end, is awesome and that is what I want Allende to do. edit: Let's tweet him and see what he says, is he still around? What happened to him or other leaders who used similar rhetoric and policies around the world during the few decades of the cold war? Cool Bear fucked around with this message at 08:29 on Jul 26, 2014 |

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:What would you know about conditions in Chile at the time? Or now, for that matter? clueless privileged leftist posted:Pinochet was the figure-head of a military coup in 1973 against the democratically elected left-wing government, a coup which the CIA helped organise. Thousands of people were murdered by the forces of "law and order" during the coup and Pinochet's forces "are conservatively estimated to have killed over 11 000 people in his first year in power." [P. Gunson, A. Thompson, G. Chamberlain, The Dictionary of Contemporary Politics of South America, Routledge, 1989, p. 228] Still haven't even tried to critique this. You just spergily asked for citations when the citations were right there. Just admit that you're a neoliberal.

|

|

|

|

Filippo Corridoni posted:

Or at least something similar to a neoliberal.

|

|

|

|

oh look a pinochet apologist

|

|

|

|

joepinetree posted:It was Nixon who spoke that line: quote:Now, as far as original contributions go, here's one thing that generally doesn't get the attention it should: I don't think I knew about this at all! In case someone takes issue with Haslam, I found another source for this: The Overthrow of Allende and the Politics of Chile, 1964-1976, by Paul E. Sigmund. It seems that this was a point of contention within UP, but that Allende's pro-plebiscite opinion prevailed shortly before the coup. Is this commonly known, at least in Chile?

|

|

|

|

Absurd Alhazred posted:Ah, modern bureaucracies. The most despicable things are documented in triplicates. I used Haslam because it was the easiest English source you can find. But the note he quotes there, for example, comes from Jose Toribio Merino Castro's own memoir. Merino was one of the leaders of the coup, for the record.

|

|

|

|

joepinetree posted:I used Haslam because it was the easiest English source you can find. But the note he quotes there, for example, comes from Jose Toribio Merino Castro's own memoir. Merino was one of the leaders of the coup, for the record. Oh, that is damning.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:

Just saw something in this passage that I missed the first time around: did you really describe money spent on covert activities to depose Allende as "aid?" You do realize that the article you link to is not talking about money sent to Chile as "aid," but to finance covert activities, which included everything from financing the PN election campaign to paying organizations to protest and go on strike against Allende? I mean, in order to support your argument that Nixon sent economic aid to Chile, you just linked to a section about the covert money spent trying to overthrow Allende...

|

|

|

|

joepinetree posted:The idea that intervention came as a response to Allende expropriating American businesses is bullshit So, let's avoid being a typical D&D thread and make sure we're always talking directly at each other. In the post that spawned this derail, and that I quoted in the OP, Helsing said Nixon immediately terminated most of its foreign aid after Allende took power. I posted documents to flesh out the financing situation and show that no, that was not true, instead withdrawal of aid was threatened as a response to illegal (from the POV of most of the world) expropriation of American companies. For sure, the CIA (and the Russians, too, but there we have less information) had been meddling in Chile for awhile. Intervention in that sense had absolutely been going on before the expropriation. joepinetree posted:This is, again, not true. Originally the strike was about freight rates and difficulties in obtaining parts. As a result of the strikes the government seized some trucks. As with most other economic phenomenon, it later came out that the trucking strike was financed by the CIA: I stand corrected! But does striking over price controls and shortages of parts (among other things) make things different? Document 311, page 867 of the original report but 824 of the PDF posted:Truckers’ grievances with the Allende government (over such issues as freight rates and the scarcity of spare parts) formed the ostensible basis of the trucking strike which began last week in southern Chile and has spread to the more populous central zone.2 Government moves to counteract the strike by jailing key union leaders, impounding trucks and declaring zones of emergency appeared to stiffen resistance and gain sympathy from other groups. Shopkeepers and small businesses joined the strike with at least 65 percent effectiveness, and some other professional groups (including engineers and doctors)have publicly indicated they might follow suit. The opposition political parties have announced their support of the strike. While Allende has called for moderation, he has also extended the It's important to differentiate "CIA spent some money to support a thing" from "A thing happened because the CIA spent money on it." Especially in Chilean politics. The grievances behind the initial strike were real and the heavy handed government response escalated the matter into a general strike against the UP. How much was the CIA involved? This is how the footnote of the same document describes CIA involvement. quote:A nationwide truckers’ strike began on October 10 and grew into a protest against the UP government. According to the report of the Senate Select Committee to Study Govern-ment Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (Church Committee), “antigovernment strikers were actively supported by several of the private sector groups which received CIA funds.” When the CIA learned that one private sector group had broken the Agency’s ground rules and passed $2,800 directly to the strikers, the Agency protested, but continued passing money to the group. (Covert Action in Chile, p. 31) So, private groups the CIA gave money to also gave some money to the strikers, over objections (probably tepid) by the agency. Anyone want to hunt up Covert Action in Chile, if it's available? Maybe it identifies which groups and how much. joepinetree posted:First, the third stage of the nationalization of the copper industry passed congress by a unanimous vote, so it is misleading to say it was Allende who did anything. That is a really awesome source and I would encourage everyone to read the whole thing. It's really interesting. joepinetree posted:Not to mention that as controversial as you may feel those nationalizations were, not even Pinochet reversed them or changed anything related to compensation. Nationalization of copper was extremely popular in Chile, and eventual full nationalization was the goal of the Frei administration in the late 60's. IMO that was ultimately a good thing. However, Allende's confiscatory approach was extremely controversial and caused a lot of unnecessary turmoil. There was certainly some normal commercial dickering over the value of the assets, but the two largest categories of deductions were for "excess profits" and "loans the government deemed had not been invested usefully", which were criteria related to social justice rather than business or the economics of the mines. And when taken in total the scheme was highly questionable. From the same document you linked: Fleming: The Nationalization of Chile's Large Copper Companies in Contempo, p.638-639 posted:Thus, it is obvious that Chile's deductions of damages from the compensation awards provided for the mining enterprises are not entirely unprecedented in interstate practice. In fact, the concept of retribution for alleged injustices, in and of itself, might be viewed as quite justifiable. However, in the Chilean case, this issue becomes considerably more debatable since, when these deductions for fiscal and social misfeasance are combined with the other deductions discussed, the total of the deductions greatly exceeds the original base book values of several of the mining enteprises.252 In effect, com-pensation to three of the five nationalized mines was wholly eliminated by the State's deductions. Of the three North American firms affected by the reforms, only the Cerro Company was not charged with owing the Chilean state millions of dollars. The book value of Cerro's Rio Blanco (Andina) mine was listed at $20,145,469.44. This valuation was reduced by only $1,875,768.09 following deductions for the mineral deposits themselves and the minor deductions for assets received in defective condition.2 Graciously, the Chilean government declined to go after Kennecott for 310 million dollars. quote:However, the United States has not confined its condemnations of Chile's acts to mere diplomatic rhetoric. Largely as a consequence of Chile's treatment of the American-owned mines, financial aid from most private and public sources in the Western world has virtually been halted. Lines of short-term credit have fallen from $220 million in August 1970, to $32 million in June 1972.277 There have been no new loans to Chile from the World Bank during the last 22 months, for instance, although Chile has claimed to have met all the necessary technical requirements for such loans.178 This stifled flow of funds from the World Bank is generally attributed to United States opposition, on the ground that the Chileans are no longer credit-worthy. Mentioned as a footnote (because the document is about copper nationalization, nationalization of other businesses was going on at the time. Footnote 55 on page 10 of the PDF posted:To date, Allende's socialization efforts have resulted in the nationalization or negotiated sale of large sectors of the foreign-owned business community. In addition to the five mining enterprises of the Gran Mineria and Andina, the affected foreign concerns include: Alimentos Purina (a subsidiary of Ralston Purina), Anglo- Lautaro (a nitrate industry with a 51 per cent ownership interest held by the Chilean government), Bethlehem-Chile Iron Mines Co. (a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel), Chitelco (Chile's telephone company of which 70 per cent is owned by ITT), Ford Motor Co. of Chile, Industrias Nibco (50 per cent ownership held by Northern Indiana Brass Co. and 25 per cent held by European investors), RCAChile, and South American Power-Chilectra (70 per cent ownership interest held by the Boise-Cascade Co.). Furthermore, the new administration has nationalized a large portion of the banking industry in Chile, including Banco de Brasil, Banco Frances e Italiano, Bank of London and South America, First National City Bank, and the Bank of America. The combined effect of all of this was to push international business out of Chile and make it much harder to get international financing or capital, for understandable reasons. Since Chile's economy depended on trade that meant the Chilean economy and Chilean people were absolutely screwed. Frei's more moderate approach of negotiated nationalization would have avoided much of that at the expense of slowing down the process and I guess causing revolutionary socialists to pop less wood. joepinetree posted:Now, as far as original contributions go, here's one thing that generally doesn't get the attention it should: I've heard that story a couple of ways. In one the president confided in Pinochet that he was going to announce a plebiscite and the general replied something like "Very wise, Mr. President, but if you want my advice wait three days". The account above is probably an accurate one. joepinetree posted:Just saw something in this passage that I missed the first time around: did you really describe money spent on covert activities to depose Allende as "aid?" You do realize that the article you link to is not talking about money sent to Chile as "aid," but to finance covert activities, which included everything from financing the PN election campaign to paying organizations to protest and go on strike against Allende? Again, let's not be D&D ok? The quote below the link contains the info I linked to the article for and it's talking about aid money (in response to Helsing's assertion that Nixon cut off all financing). Quote refresh posted:The U.S. provided humanitarian aid to Chile in addition to forgiving old loans valued at $200 million from 1971-2. The U.S. did not invoke the Hickenlooper Amendment which would have required an immediate cut-off of U.S. aid due to Allende's nationalizations. Allende also received new sources of credit that was valued between $600 million and $950 million in 1972 and $547 million by June 1973. The International Monetary Fund also loaned $100 million to Chile during the Allende years.

|

|

|

|

Filippo Corridoni posted:Still haven't even tried to critique this. You just spergily asked for citations when the citations were right there. First, that's a repost of the poo poo you originally posted without any cites at all. Second, what do you want me to say about it? I do not want to spend time or energy defending Pinochet. I find that loving distasteful, and the point of starting this conversation wasn't to argue for how great the dictatorship was (it wasn't). Rather, it was to educate people about what was going down during and prior to the Allende administration so that people had some context and could come to appreciate why, in Chile, this is a much more nuanced topic than it seems to be for the neck bearded internet leftists here.

|

|

|

|

Absurd Alhazred posted:What do you think about Michelle Bachelet? Any good critiques of her current plans? Working on this. Don't have a ton of time. The TLDR - Bachelet is making a lot of (business) people nervous. She proposed a tax reform that would have eliminated the corporate veil WRT taxation and passed retained earnings (money taxed at the corporate rate but left in the company) through to the owners as personal income. This would have raised the corporate rate, effectively, from 20% to 35% and utterly hosed the shareholders of public companies with detrimental effects in Chile's stock market, for pension funds, etc. That did not happen, thankfully, and the compromise that seems set to pass raises the corporate rate from 20% to 27% among a bunch of other more technical things. She is committed to education reforms that, partly because of the tax compromise and partly because the original tax proposal was total fantasy anyway, there is no way to pay for. Free higher education for all Chilean students would cost approximately 9 billion dollars, or about 3% of Chilean GDP. Her education minister had talked about buying all the hybrid public-private institutions and making them fully public. Depending on whose estimates you take on the value of those concerns the cost could be 5 billion or 17 billion. Either way the money isn't there. Education is a big sexy issue competing right now with issues like public health spending (very underfunded) and Chile's growing energy needs. *Axes Hydro Aysen. Declares victory for SOCIAL JUSTICE. Pays highest rates for energy in Latin America and wonders why poo poo is so expensive to make here* And in general there's a populist vibe that reminds many people uncomfortably of the bad old days. That said, Bachelet enjoys wide support in general despite approval having come down from the stratospheric heights it attained during the primaries.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Working on this. Don't have a ton of time. quote:[Bachelet] is committed to education reforms that, partly because of the tax compromise and partly because the original tax proposal was total fantasy anyway, there is no way to pay for. Free higher education for all Chilean students would cost approximately 9 billion dollars, or about 3% of Chilean GDP. Her education minister had talked about buying all the hybrid public-private institutions and making them fully public. Depending on whose estimates you take on the value of those concerns the cost could be 5 billion or 17 billion. Either way the money isn't there. Education is a big sexy issue competing right now with issues like public health spending (very underfunded) and Chile's growing energy needs. When you get to the bigger piece, I would be interested in what competing proposals there are for education reform; and, well, to start with, what is perceived as being deficient in the status quo.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:And in general there's a populist vibe that reminds many people uncomfortably of the bad old days.

|

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:Working on this. Don't have a ton of time. How does it feel to be a Matthei voter?

|

|

|

|

Badger of Basra posted:How does it feel to be a Matthei voter? A little dirty TBH. I would have voted for Velasco but nobody from the center left was going to win vs. Bachelet.

|

|

|

|

Bulky Brute posted:Ah yes, those terrifying Allende years where the chilean petite bourgeoisie lived under economic and political uncertainty i.e. what workers live through every single day of their lives. To be fair, those where bad old days. They just have literally nothing to do with Allende. Bachelet sounds cool though. edit: Though it is funny that the businesses aren't learning their lessons. If populism is making you fearful, don't fight back, it will only make it worse. CharlestheHammer fucked around with this message at 19:35 on Jul 28, 2014 |

|

|

|

wateroverfire posted:So, let's avoid being a typical D&D thread and make sure we're always talking directly at each other. In the post that spawned this derail, and that I quoted in the OP, Helsing said Nixon immediately terminated most of its foreign aid after Allende took power. I posted documents to flesh out the financing situation and show that no, that was not true, instead withdrawal of aid was threatened as a response to illegal (from the POV of most of the world) expropriation of American companies. For sure, the CIA (and the Russians, too, but there we have less information) had been meddling in Chile for awhile. Intervention in that sense had absolutely been going on before the expropriation. How about we also avoid that "typical D&D thread" part where people who get contradicted immediately go "D&D amirite?" This thread is all in one page, we don't really need to argue over what you or someone else really said. Of course, the bit he said about terminating "most" of the aid is correct, as evidence is once again clear as day that aid was cut prior and increased after the coup. Of course, aid itself was a minor and almost insignificant part of what happened there. The main thing is that Nixon essentially froze the credit Chile got from most foreign institutions, like the IDB, IRBD, Import Export bank, etc. For an export oriented economy like Chile that was essentially a blockade. Regarding the cutting of aid and assistance (note the date): http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc09.pdf Regarding the economic relief after the coup: http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB8/docs/doc10.pdf quote:I stand corrected! But does striking over price controls and shortages of parts (among other things) make things different? No, it is not important to differentiate, because they are no different. It is sort of a purely rhetorical exercise to speculate whether or not the money flowing into the opposition helped them decide to go on strike or not. What is important is that without external financial support, the truck company owners would not have been able to stop the country for nearly a month. quote:

First of all, note that I chose that document precisely because it was an English source that opposed the nationalization (also note the date). So that even by that type of source what you had said regarding nationalization wasn't true. quote:Again, let's not be D&D ok? The quote below the link contains the info I linked to the article for and it's talking about aid money (in response to Helsing's assertion that Nixon cut off all financing). First, the link led directly to the covert operations bit. Second, did you notice that the paragraph you quote is in stark contrast to the rest of the section you mentioned? That is because that last paragraph is based on a frontpagemag "Article." I don't know if you are aware of what front page magazine is, but might as well quote world net daily at that point. Now, the interesting thing is even frontpagemag (the source for your wikipedia quote) admits that all those loans were agreed on before Allende took power, and no new loan agreements were made afterwards. The part about the IMF is specially hilarious, since it says "between 1970 and 1973." Here's the reality: The last loan the InterAmerican Development bank gave Allende was in January of 1971. It only lent Chile money again after the coup. The World Bank made no loans to Chile while Allende was president. The IMF made a few loans to cover export shortfalls (mostly because if they didn't whoever Chile was importing from would go unpaid), but not the more usual standby loans. And all of this info can be found on Paul Sigmund's book on the matter mentioned above, and he hardly be claimed to be biased in favor of Allende (prior to the release of documents showing Nixon and Kissinger pressuring these institutions to cut off Chile Sigmund argued that the US had not exerted much pressure on these organizations). Luckily, we also have easy to find economic data available to us: http://databank.worldbank.org/ Lot's of data are not directly available on this site, but quite a few important ones are. For example, select Chile and Net ODA (%of GNI). Net ODA refers to net flows of Official Development Assistance as a percentage of gross national income: 1968 1.271328492 1969 1.233029595 1970 0.850003907 1971 0.465984943 1972 0.447106847 1973 0.307695632 1974 0.154510686 1975 1.829608533 Notice a pattern? Keep in mind that there is a lag in approving new aid, but not on cutting aid (i.e., aid approved now will only be disbursed in a few months, but if aid is cut it can stop immediately). That explains why 1970 already shows a decline, and it doesn't increase back again until 1975. Same for all multilateral loans  Full disclosure, the image above comes from the Committee for Abolition of Third World Debt, which is fairly left leaning. But the graph contains the source of the data, so you can check for yourself if you'd like. joepinetree fucked around with this message at 23:10 on Jul 28, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 25, 2024 06:21 |

|

joepinetree posted:How about we also avoid that "typical D&D thread" part where people who get contradicted immediately go "D&D amirite?" This thread is all in one page, we don't really need to argue over what you or someone else really said. Of course, the bit he said about terminating "most" of the aid is correct, as evidence is once again clear as day that aid was cut prior and increased after the coup. Of course, aid itself was a minor and almost insignificant part of what happened there. The main thing is that Nixon essentially froze the credit Chile got from most foreign institutions, like the IDB, IRBD, Import Export bank, etc. For an export oriented economy like Chile that was essentially a blockade. On the topic of the "economic blockade", Paul Sigmund wrote an essay for the January edition of Foreign Affairs that investigates the question of Washington's roll in the disappearance of credit toward Chile by looking at the timing of credit decisions, notes from the senate hearings after the coup, corporate memos from ITT (AT&T) and interviews with sources at various foreign institutions. Whole article reproduced below because it's worth reading in full and because at FA you have to register (though it's free). tldr - poo poo was kind of complicated. When you look at the timing and statements by the principals, it's apparent that international loan and bank credit reductions were made in response to worsening economic conditions and a political environment that implied increased repayment risk. It's also clear that Washington applied pressure to block some financing - sometimes successfully and sometimes not - to force Chile to the bargaining table after the copper expropriations, and that the rhetoric surrounding the 1970 election had a lot of people nervous about the ideology of Allende. Chile obtained a lot of funding from non-US sources despite Washington's eventual opposition. In Sigmund's own words: quote:The problem, of course, is to sort out motives. Progressively, the negative long-term economic outlook provided an excuse for those who wished to put pressure on the Allende government by cutting off credit. That excuse, a bit flimsy at the outset but increasingly persuasive by the end of the year as Chile's economic problems mounted, was that the Chilean government was not "credit-worthy." It is thus hard to distinguish between what could have been seen by many to be legitimate reasons for not making loans and credits available (serious doubts about Chile's likelihood or capacity for repayment) and illegitimate ones (economic warfare in defense of private corporations or in order to promote a military coup). While not finally conclusive, a review of the policies of various institutions during this period may be helpful in making this assessment. quote:A striking aspect of the world reaction to the military coup that overthrew Salvador Allende as President of Chile in September 1973 has been the widespread assumption that the ultimate responsibility for the tragic destruction of Chilean democracy lay with the United States. In a few quarters, the charge includes an accusation of secret U.S. participation in the coup. However, a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, headed by Senator Gale McGee, has just investigated this accusation and concluded that there is no evidence of any U.S. role whatever. quote:No, it is not important to differentiate, because they are no different. It is sort of a purely rhetorical exercise to speculate whether or not the money flowing into the opposition helped them decide to go on strike or not. What is important is that without external financial support, the truck company owners would not have been able to stop the country for nearly a month. On what basis would you be confidant of that? quote:First of all, note that I chose that document precisely because it was an English source that opposed the nationalization (also note the date). So that even by that type of source what you had said regarding nationalization wasn't true. I'm not sure how to parse this at all. That source laid out both sides of the dispute and the relevant international law and precedents, and by the weight of the evidence the law was not on Chile's side. What would you consider a neutral source? What was it that I said about nationalization that wasn't true? Absurd Alhazred posted:No rush, Chile will still be around next week! Hopefully.

|

|

|