|

Edit: Big effort post in the wrong thread. Edit 2: Oh god I'm a new page. Uh... let's go Liberal Team Goth/Brittania! Best friends forever! Val Helmethead fucked around with this message at 00:36 on Jul 10, 2019 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 19, 2024 16:41 |

|

I say bring back some Triarius cousin and crown them emperor ! They would never have gotten us into these messes

|

|

|

|

I kinda wonder if this is where we're going to have a late Napoleon figure since we didn't get one earlier, as the Brits were more interested in glorious isolationism than spreading the revolution.

|

|

|

|

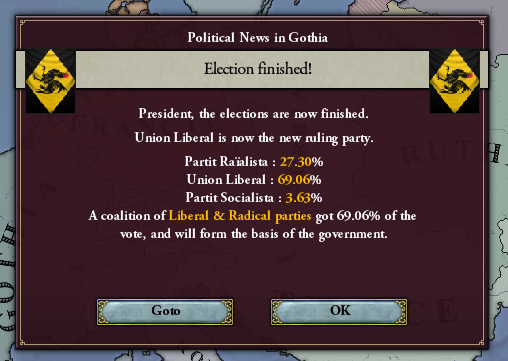

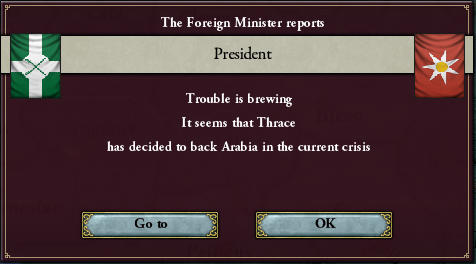

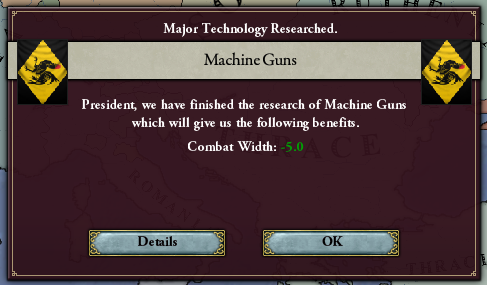

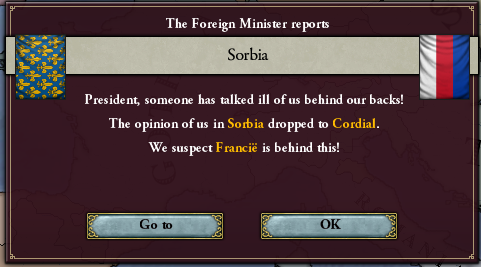

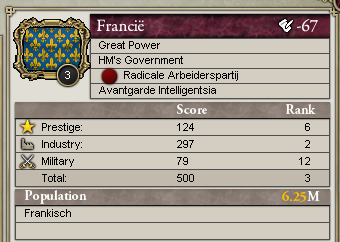

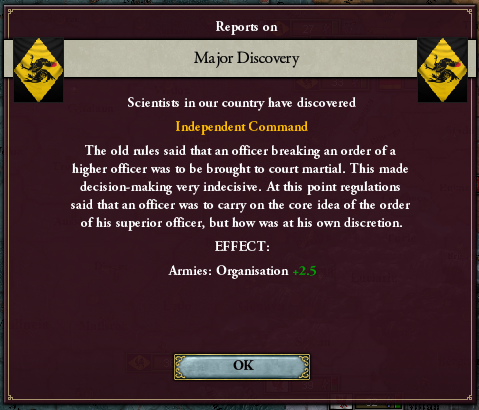

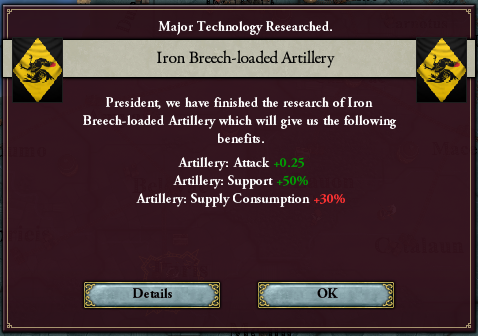

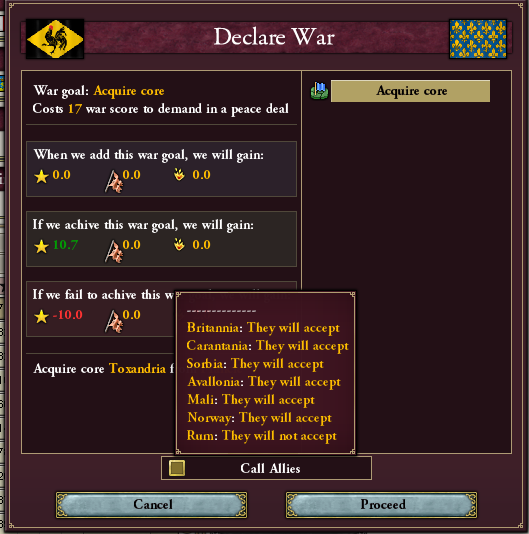

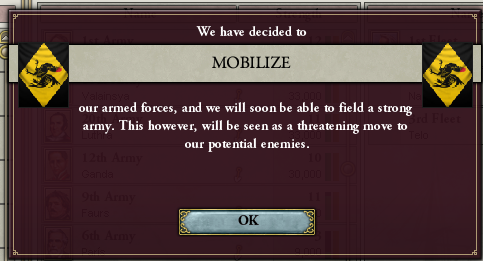

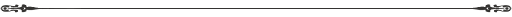

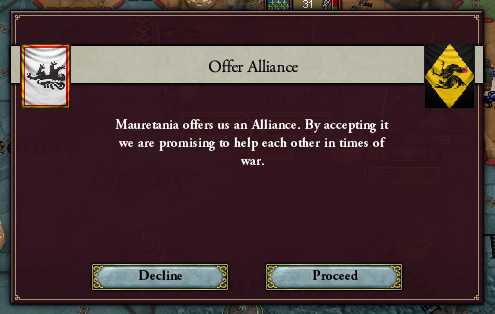

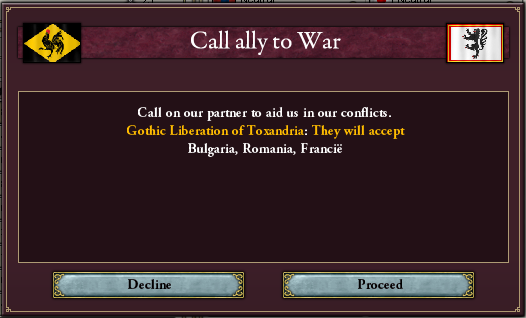

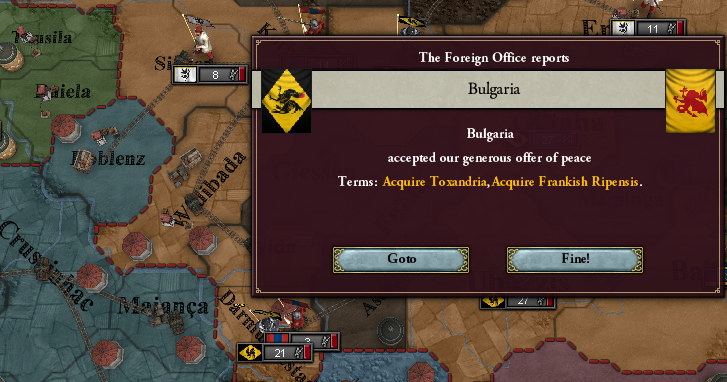

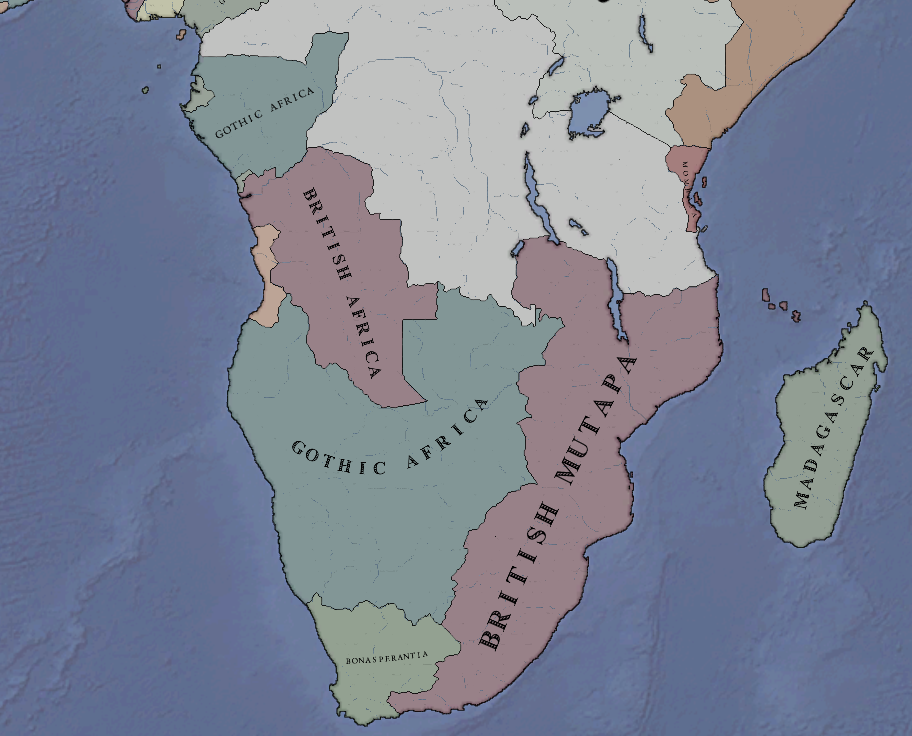

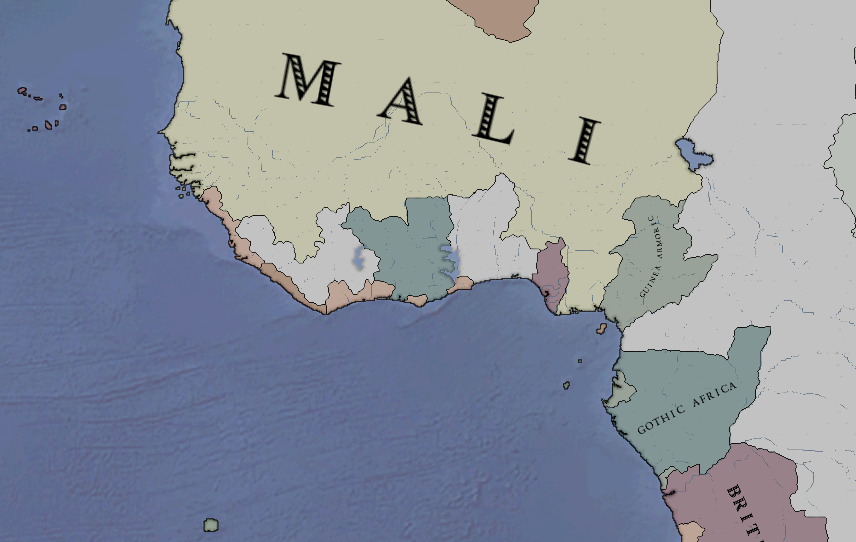

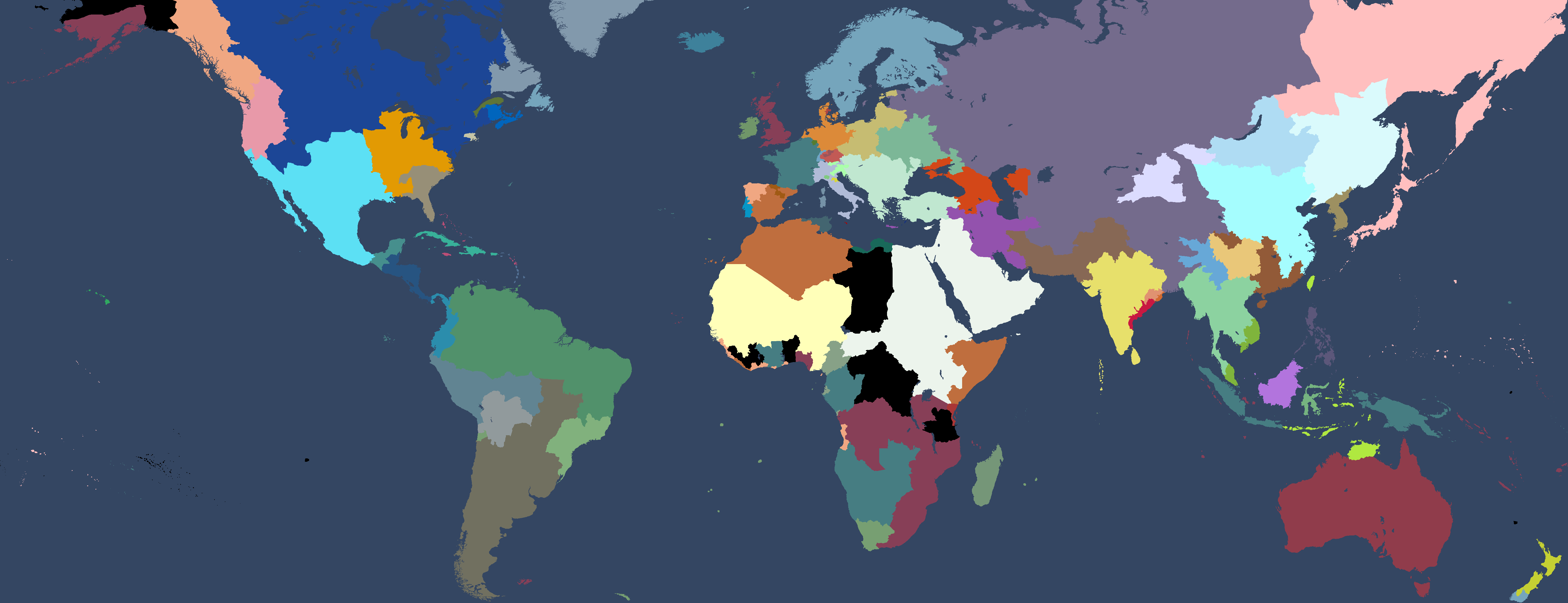

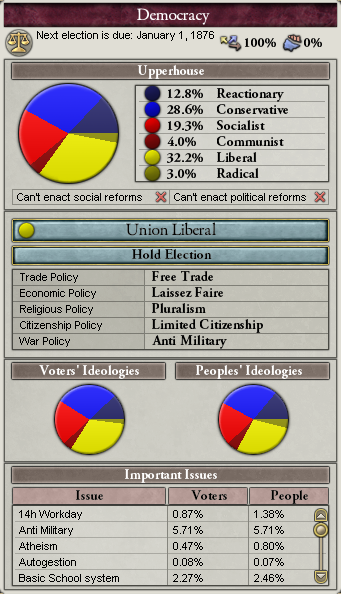

Chapter 80: Revenge 1871-1875 The Republic of Gothia's solution to domestic unrest, promoting a newfound support for a policy of “Revenge Above All Else”, offered some immediate benefits to Gothia, but in the long-term may have sowed the seeds for more intense unrest at home.  Gothia had, in the 8 years since the collapse of its venerable monarchy, regained much of its former stability and standing. New alliances, notably with the Republic of Britannia, had been forged, and the rebellions of the mid-1860s were little more than a fading memory by 1871. Under the guidance of President Jehan Bursiac, the Goths had followed a policy of Revanja, focusing on an anti-Frankish policy, nationalist agitation for the recovery of provinces lost to Francië in 1863, and trying to suppress domestic disputes for the sake of a united front.  Not everyone agreed with Bursiac's idea of Revanja, but the suppression of domestic fractures was enough to keep the country superficially calm.  It also gave the party in power sweeping powers to determine what counted as a “disturbance” and what did not; naturally, anything which challenged the power of the Union Liberal was ruled a “disturbance”.  To President Bursiac's satisfaction, this policy paid off handsomely in the 1871 elections. The Liberals maintained a firm majority, the old conservative Royalists won little more than a quarter of the vote, and the Socialists were so insignificant that they posed no threat to the liberal order at all.  Other countries were faring less well with internal tensions. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, long in control of the Arabian Peninsula, faced a surge in support for Arabian nationalists late in 1871. Mass protests struck several towns in the peninsula, and government functions ground to a halt as Arab workers and government clerks engaged in a general strike.  Tensions escalated when the Thracian Republic loudly announced its support for the Arab nationalists, promising “to protect the rights of all those who cannot enjoy a say in their governments”. While Gothia was allied to Jerusalem, the government hesitated in backing the kingdom after Thrace's public display of support for the Arabs.  Covert inquiries were made about the army's war-readiness. The army had indeed started complementing some of its elite units with companies equipped with hand-cranked rapid-firing guns, but these orders were still being processed in early 1872, and no real doctrine had been developed for their use.  Machine guns did open up new possibilities elsewhere, however. With advances in medicine and armaments, it was finally possible for Europeans to explore Africa beyond the confines of malarial trade ports.  Due in part to the government armament survey, Gothic exploration and colonization began in 1872, with several explorers eagerly rushing into the hinterland beyond Pòrt Secheval. Although the explorers found very little, the reports they sent back to Gothia were full of glowing praise for a “promising land”.  For its part, Thrace eventually chose to drop the issue of Arab liberation, and the crisis which sparked the machine gun survey and initial African forays fizzled out in May of 1872.  Other diplomatic considerations soon raised their head, however. Shortly after the Arab crisis simmered down, the Franks began actively trying to drive a wedge between Gothia and its ally Sorbia, who together posed a severe threat to the Franks' western and eastern borders. The Gothic government hoped to use their alliance with the Sorbs as a deathly vice to crush the Franks, and the Franks were no fools- but they were sloppy enough in their propaganda efforts that the Goths caught on to their plan early on.  The Franks were particularly abhorrent to the Liberal, republican government of Gothia. Not only did the monarchy still stand strong in Francië, but they did so with the backing of communists. Even Frankish commentators recognized the bizarre nature of their government, but after previous failed uprisings the Radical Worker's Party had decided to take their seats in Francië's parliament, and the monarchy ultimately refused to ban the communists lest tensions be inflamed again.  As 1872 drew to a close, Bursiac's government issued another survey to the army. This time, along with general questions about war-readiness, the government asked about current war plans and current tactical doctrines.  The army, for its part, reported on numerous reforms, including radical changes in the traditional command structure and greater leeway for officers in the field.  Arms, too, were improved, with machine gun companies filling out while new cannon models were introduced to older artillery units.  Throughout 1872 and 1873, the government also engaged in a major diplomatic push in Europe, securing alliances with several countries, and ensuring that its alliance with Britannia remained strong.  Finally, by late summer of 1873, Bursiac's government felt prepared. Domestically, the country was stable again after the long years immediately following the collapse of the monarchy, when rioting and insurrection had been rife. The army, reduced to an anemic remnant in the 1860s, was now modernized and rebuilt. Gothia's new alliances were numerous and strong. If there was any time for Gothia to strike back at the Franks, now was the time.  And so, on August 19th, 1873, the Republic of Gothia declared war on the Kingdom of the Franks.  Both the Gothic and Frankish alliances sprang into action to support their friends. Most importantly to the Goths, Britannia honored its call to arms and vowed to take an active role in the war.  On the other side of the conflict, Francië's allies, Romania and Bulgaria, sprang to the defense of the Franks. Bursiac waved away concerns about their involvement, vowing to win the war by Christmas.  To that end, Gothic reserves were called up almost immediately. If the war was to be won quickly, then Gothia had to throw everything it had at the war.  The trumpets, Maria decided, were the worst. The declaration of war hadn't been a surprise to anybody who read the papers. The liberals had been beating the drums of war for months, years even, and sometimes they had literally beat the drums in incessant 'Remembrance' parades. Now, those same bands had brought out their instruments, and were striking a jaunty tune as a column marched down the main road through Amalhac, bearing banners with striking, evocative slogans such as 'The Rhine is Ours', 'Drive The Franks Out Of Gaul', and 'Let's Win'. Her son, Evaric, clapped as someone marched by with a placard showing the King of Francië wielding a hammer and sickle. She frowned, but as the placard-bearer passed by, Evaric yelled “Yeah! Death to kings!” to the befuddlement of the marcher, and Maria's frown changed into a relieved smile. She'd raised her son well. The rest of the parade passed without incident. She sighed. Her husband would've loved the spectacle, but the parade was happening right in the middle of his shift at the railyard. At least she and Evaric could tell him about it later. As the last marching band waddled around the corner, someone spoke up behind her. “Madam?” Maria turned, and saw a constable standing next to the marcher her son had cheered at earlier. While the officer was stony-faced, the marcher was as red in the face as the king's had been in his placard, and appeared to be teetering on the edge of a furious rage. The constable coughed. “The boy,” he pointed at Evaric, “is he yours?” She nodded. “Yeah, that's my son. What's the matter, sir?” She knew it was best to play innocent when the law got involved. The marcher burst in. “That boy was yelling revolutionary slogans! He's a menace!” Maria stepped between her son and the accuser. “My boy called for an end to monarchy- we're a republic, so what's so bad about that?” The officer said nothing, but the accuser continued. “Who cares about kings? The only people who scream about that are socialists.” “And?” “And socialists oppose the war! They're allies of the Communists! They're undermining the honor of our nation!” It took a moment, but then Maria doubled over laughing. “Good Lord, that's the most ridiculous thing I've heard all week. I'm a socialist, and even though I oppose-” She caught herself, but too late. The accuser stared at her. “You're a socialist? You oppose the war?” The constable spoke up. “Madam, I regret to inform you that seditious talk carries serious penalties. Please, come with me to the station.” Maria was dumbfounded. “Wait, what sedition? All I said was- I didn't even- that's not enough to-” As she stumbled through her words, her accuser cracked a vicious grin. The constable wasn't having any of it. “Please, come with me to the station,” he repeated as he pulled out a pair of handcuffs.   Gothic troops were, for once, well-positioned at the outbreak of war. The Franks were the first to cross the border and attack, but the Goths had two armies stationed nearby just to counterattack and press on into Francië.  In south, Francië called its ally, Romania, into the war immediately. There, Gothic and Romanian forces were numerically matched, and whoever tried to attack first would have to grapple with defensive lines in the Alps.  In the east, Sorbia had some armies ready for combat, but none were stationed by the Frankish border when war broke out. Although they accepted the Goths' call to arms, they were not ready for war- something which President Bursiac accepted, and in some ways wanted, as an aggressive Frankish offensive into Sorbia would draw Frankish troops away from the western front.  Other countries were quickly drawn into the conflict, notably Norway on the Goths' side and Bulgaria on the Franks' side. The conflict was quickly spreading out across the map.   Despite the expanding scope of the war, the Goths were focusing solely on the Rhenish front. Battles raged across both sides of the border in the opening month of the war, as Franks marched south from Toxandria and Goths crossed the Rhine near Widibada.  In the south, Gothic forces soon withdrew from their initial Alpine fortifications, as Romanians spread their forces out and threatened to outflank the Gothic line.  Nonetheless, the Goths made a good showing in the first weeks of the war, winning the battles they chose to engage in, even if they endured some significant losses in the process.  Their victories inspired the Mauretanians, sensing which way the balance of power was shifting, to offer a military alliance to the Gothic Republic.   Bursiac's government immediately responded with a vehement “YES”, and promptly requested Mauretanian aid in the war. The Mauretanians, for their part, accepted the call, bringing all the manpower of North Africa and Hispania to bear against the Frankish-Romanian-Bulgarian alliance.  Invigorated by the news of the Mauretanian intervention, Gothic troops in the south went on the offensive, concentrating their forces against specific corps in the Romanian army rather than trying to spread their strength and attack the entire Romanian line at once.  This approach proved to be highly successful, and became the basis for the Goths' overall strategy on the Romanian front.  By October of 1873, just two months after the outbreak of war, the course of the conflict along the Western Front had gone decisively in Gothia's favor. Not only were the Goths winning battle after battle, but Gothia's allies had fully mobilized and added their weight to the fight. British troops poured into Frankish Toxandria, and the Mauretanians were rushing to the Alpine front to fight the Romanians. In Europe, Gothia's allies quickly came together to fight their enemies.  Abroad, however, competition between the allied powers was beginning to heat up. Following the initial surveys into the Namibian interior, Gothic officials had begun establishing new outposts in Southwest Africa, expanding the republic's influence in the region. They were not alone, however- the British built an outpost at the mouth of the Congo River, staking their own claim, and Gothic officials staring at a map of Africa soon realized that an aggressive colonial push by the British could threaten to surround and contain Gothic South-West Africa. Additional plans were drawn up, and small Gothic expeditions soon peppered the coasts of Sub-Saharan Africa.  But, for the time being, Gothia's focus was on the war and Europe. A Romanian thrust in November threatened the capital, Liyun, but Gothic forces were again able to concentrate and save the city.  The Romanian front was the most chaotic theater in the whole war. While the Franks crumbled along the Rhine, the Romanians were able to repeatedly push into Gothic and allied Carantanian territories. Gothic troops were able to defeat the Romanian armies in battle, but weren't able to defeat all the Romanians at once, leaving the foe to press into allied territory wherever Gothic troops were not present.  The Gothic solution was simply to disregard short-term territorial losses and bleed out the Romanians. If Goths kept defeating Romanian armies on the field, then eventually their military wouldn't have enough strength to adequately defend their gains along the frontier. Even by December of 1873, this approach seemed to have started working, as Romanian-occupied territories began to be abandoned by increasingly-stretched enemy forces.  Desperate for a reprieve, the Romanians attempted to split apart allied forces diplomatically, but their efforts were quickly caught and exposed. The minor damage done to relations was quickly patched up, and 1874 opened with new allied offensives into Frankish and Romanian territories.  The victory-through-bleeding approach was soon applied in the north, as the Goths, bolstered by British reinforcements, shifted their focus from the capture of Frankish territories to the destruction of Frankish armies. With concentrated forces, they enjoyed some significant successes, obliterating tens of thousands of soldiers in several battles over the course of 1874.  While the allies enjoyed successes across the Western Front, the Eastern Front remained more of a mixed bag. Sorbia, pressed between the Franks and Bulgarians, suffered some severe losses in the early months of the war, but Frankish losses in 1873 and '74 soon lessened the pressure on them. Combined with Norwegian forces, Sorbia was eventually able to at least match Bulgarian strength to the east.  Continued successes in the winter and early spring of 1874 emboldened Bursiac's government in Gothia to expand the scope of their demands. A leading article in one of the country's major papers dating from February 28th, 1874, marks the first recorded instance of an official call for the re-annexation of the Ripensis, a territory stretching from Traiecto in the west to “Coblença”, as it was called in the article, in the east.  Shortly thereafter, the Frankish line collapsed entirely. By March 15th, Gothic troops were able to break through the front lines and march all the way to Frankish-occupied territories in Sorbia. The Frankish military was falling apart at the seams.  An ultimatum was sent to the combined Frankish-Romanian-Bulgarian alliance, with Bulgaria taking the lead in negotiations. The Goths demanded the return of Toxandria and the annexation of Ripensis, demands which, while high, were relatively modest considering the significant military victories of Gothia and its allies.  On March 20th, the Gothic ultimatum was accepted, and Toxandria and Ripensis were ceded to Gothia.  The cession included Koblenz/Coblença, a city which had never been part of Gothia before and lay on the far side of the Rhine. Bursiac had sought the annexation of Koblenz as “insurance”, to provide a minor buffer against the Franks and ideally act as an initial bridgehead when and if the Franks attempted to take Gothic territories again in the future.  The acquisition of Koblenz was at odds with the otherwise nationalistic aims of Bursiac's government- it wasn't a “natural” part of Gothia, and it was overwhelmingly Frankish in character.  Gothia had also grown abroad. The surveys conducted in 1873 had led to rapid expansion of Gothic colonies in Africa in 1874, with both Gothic South-West Africa reaching the Zambezi River in the south and a second Gothic colony being established north of the Congo River. The British, too, had also expanded their African territories during the war against the Franks. New outposts solidified their gains along the lower Congo, and their inland expansion in East Africa towards Lake Tanganyika suggested that the British indeed intended to connect their western and eastern African colonies and create one great mass.  Both Gothia and Britannia also established minor colonies in West Africa. Neither colony was particularly large, as both countries were more focused on the race in Central Africa, but the West African territories already seemed poised to become lucrative colonies for the European powers. The republic had successfully avenged the humiliation of 1863, and now basked in the glory of its preeminent position as one of Europe's greatest powers. The republic which had looked so close to collapse a decade earlier could now look forward to a secure, glorious future.   ...or so it thought. The world, 1875

|

|

|

|

Yes it's back!!! And things look interesting.

|

|

|

|

hell yeah

|

|

|

|

Nice to see this going again.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

poo poo like the communist monarchy from this update makes me wonder what a Victoria game made by a Marxist instead of an ancap would look like.

|

|

|

|

GunnerJ posted:poo poo like the communist monarchy from this update makes me wonder what a Victoria game made by a Marxist instead of an ancap would look like. Funny how the engine the Ancap created basically promotes going communist to actually get poo poo done.

|

|

|

|

All caught up. That leaves just Denmark pt 2 and Azer on my read list

|

|

|

|

Rereading the ck2 part and just realized the extended reference to the Asterix comics in chapter 19.

|

|

|

|

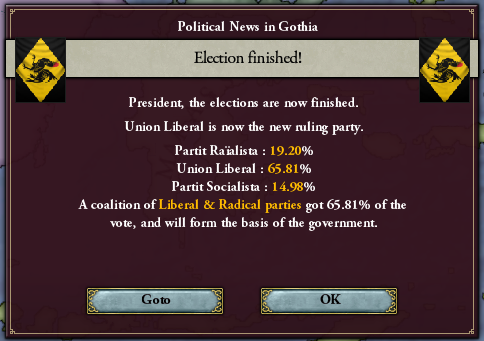

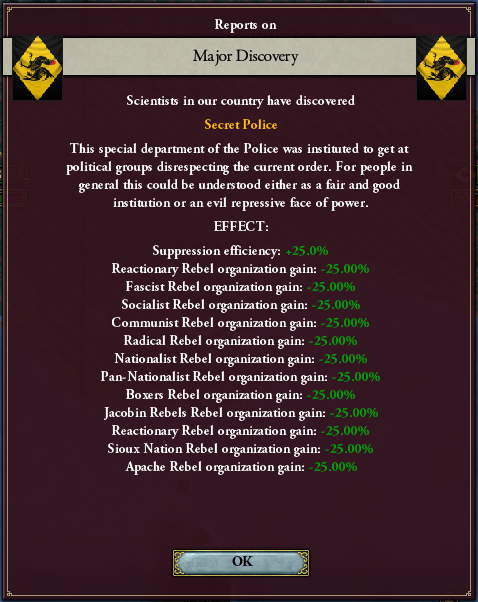

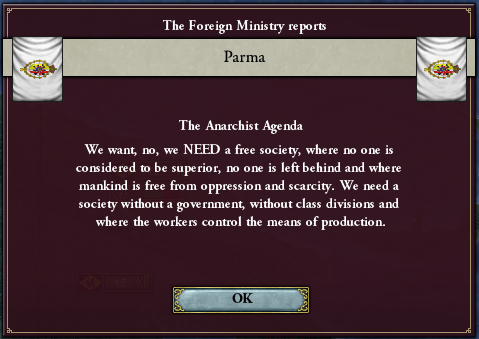

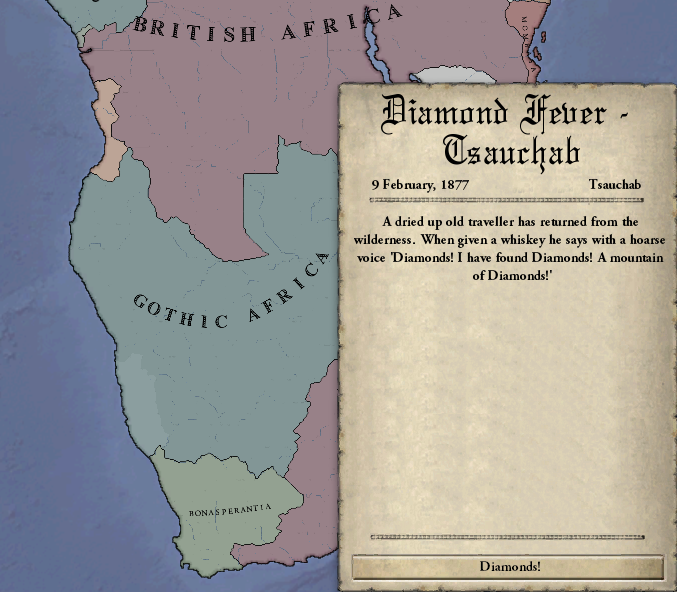

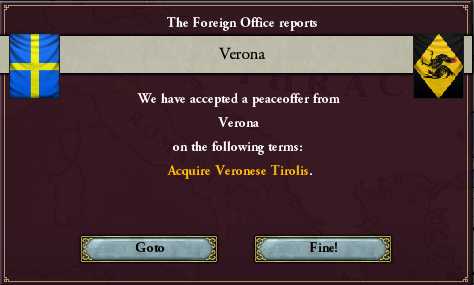

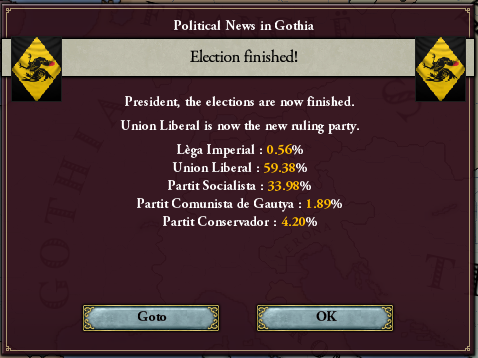

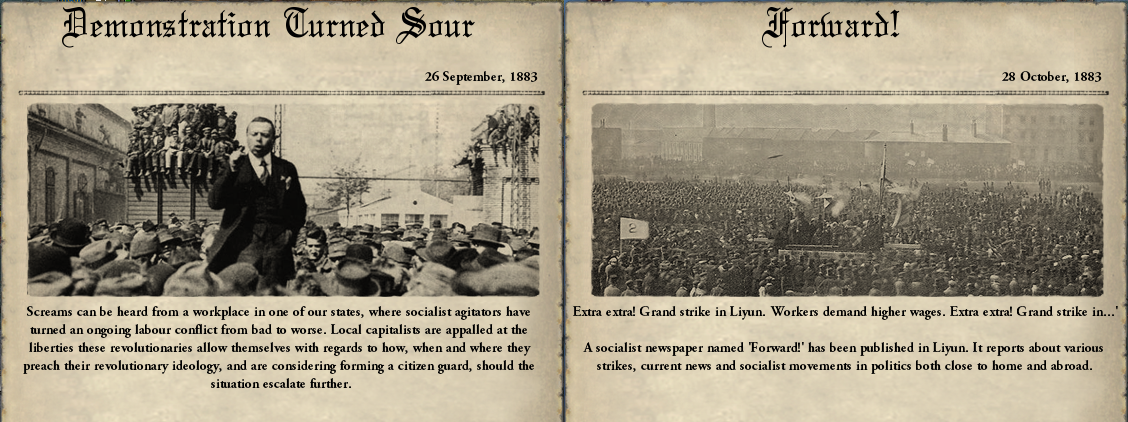

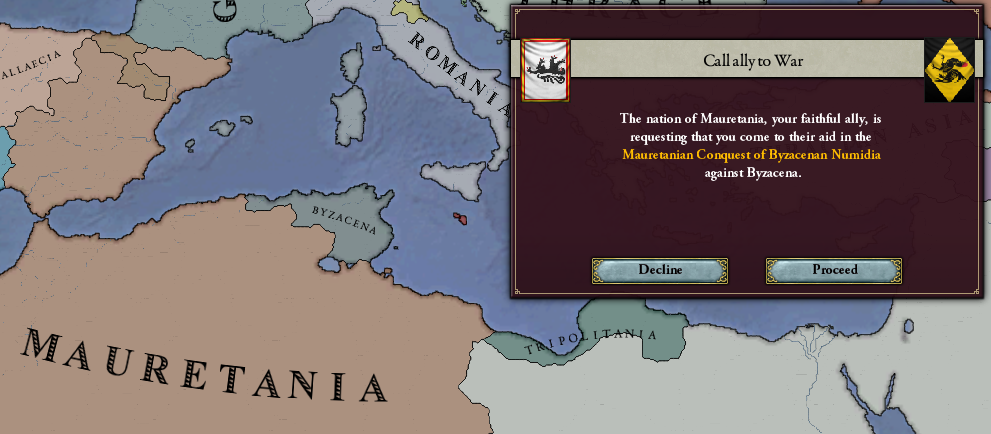

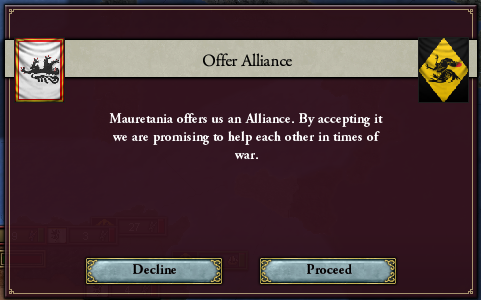

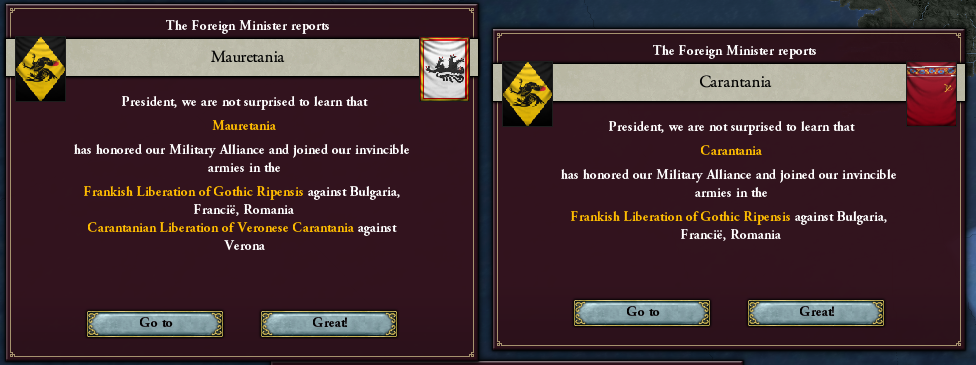

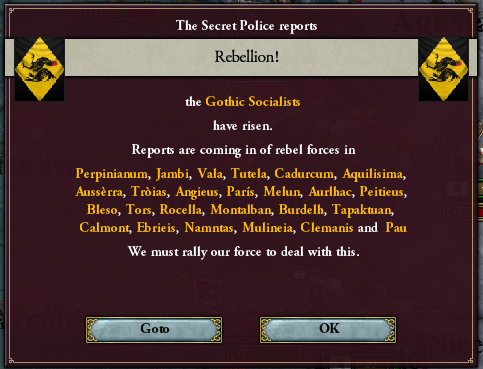

Chapter 81: The Lit Fuse 1875-1881 The Republic of Gothia's challenges did not end with the defeat of Francië and the recovery of Gothia's old Rhenish provinces. New ideologies continued to rise and threaten the republic's stability, and the liberals' hold on power turned more and more oppressive to maintain their grip, all the while Gothia continued to slowly build a new empire for itself.  Gothia in 1875 was at the peak of its game; the Franks had been defeated, the Romanians contained, and the Republic was triumphant. Gothia's borders now reached beyond the Rhine, and all the eyes of Europe were firmly fixed on the land of the Goths.  The proletarian republic of Carantania, Gothia's Central European client, was one of the first to use Gothia's power to its own advantage. In September of 1875, calculating that the Gothic government politically could not refuse a call to arms, Carantania declared war on the Duchy of Verona over its Alpine territories and brought Gothia into the conflict.  The liberal hold on Gothia's government was shakier than might have been expected. In the provinces, socialist and conservative parties both seriously vied with the Union Liberal in popularity. It was only during national elections that the Liberals were able to really put their thumb on the scales and ensure victory. Their teetering hold made the Union Liberal extremely susceptible to public opinion in the late 1870s, as could be seen with Gothic intervention in the Carantanian-Veronese war.  This vulnerability to public opinion also drove the Union Liberal's colonial policy, which drove Gothia into direct competition with both colonial enterprises from Britannia and Jerusalem. The latter posed a particular problem in Ubangi-Shari, a contested territory in the heart of Central Africa. Both Jerusalem and Gothia raced to establish a presence in the region, and even then nobody was sure how the brewing crisis could be resolved.   In the midst of these political maneuvers, the elections of 1876 began.  With the Rhine recovered, the Liberals needed to find new issues to motivate their base. In 1876, that issue turned out to be the question of citizenship- Gothia's victory over Francië had caused a significant Frankish population to suddenly find themselves in Gothic territory, and the Liberal government had struggled to find a way to reconcile Goths and Franks in the region. Now, eager to win over Gothic voters, the Liberals took a decidedly xenophobic tack.  Their nativist turn gained an unexpected boost when rioting broke out across Gothia's colonies, most notably in the East Indies. Only real Goths, the Liberals argued, were ready for the liberties of the republic.  Riding on the wave of xenophobia that they themselves had stirred up, the Liberals swept the elections 1876, handily winning an outright majority.  Following up on their new platform, the Liberals began investing heavily in security. The “Department for Public Security” (Departament de la Securetat Publica, or DSP), established in the wake of the Gothic Republic's formation, was greatly expanded. Undercover agents and plainclothes officers proliferated following the DSP's reforms, and the Department was granted the power to intercept and examine all mail sent within Gothia. Outside agitators, the government warned, would not be allowed to threatened Gothia's freshly-won glory.  Perhaps in response to this increasing domestic repression in Gothia and across Europe, a new strain of socialism emerged in the late 1870s: Anarchism.  Anarchists came from a wide variety of ideological backgrounds. Many were socialists simply wary of Karel Marx's school of thought, others were ardent trade unionists, some came from a liberal background who had radicalized themselves into being agitators for absolute liberty, and some simply had an instinctive anarchist tendency. These disparate interests came together in different ways; the idea of autogestion- workers' self-management- appealed strongly to the radical trade unionists, and the anti-Marxists found a receptive audience among anarchists when they espoused a rejection of militarism and the abolition of armies. Theoretically, the anarchists were in favor of commerce without borders, but in practice the likelihood of revolution not simultaneously erupting and winning across the globe meant that the anarchists positioned themselves to be in favor of more insular markets, wary of engagement with capitalist markets.  The new anarchist movement was unlikely to gain any traction, at least not immediately. While the Gothic Republic on one hand increased its oppressive powers, it also continued to boom economically. A diamond rush in Namibia early in 1877 was just one of many rushes and bubbles that kept injecting gold into the Gothic economy during this period.  This prosperity was only ever felt by the Goths themselves, however. The Republic's growing number of colonial subjects felt nothing of metropolitan Gothia's riches- if anything, they were exploited even harder to keep the flow of money going.  Other European countries pursued their own ways of expanding their colonial influence. Britannia, notably, took a leading interest in the possibilities of India. The country decided to make something of its plans in the spring of 1877 when unrest hit the southern regions of the Kingdom of Gujarat- the British intervened and demanded the liberation of Mysore. The Gujaratis capitulated before the other European powers could even react, and a Republic of Mysore was quickly established in southern India. Britannia “offered” to help Mysore organize itself. Naturally, British advisors were soon found at all levels of administration in the new Mysorean republic.  Mysore's “liberation” was the first major loss of territory experienced by Gujarat, but it would not be the last. Moreover, Britannia's actions caused the rest of Europe to become alarmed at the possibility of an India split between Britannia and Bulgaria, the latter already in solid hold of Bengal. This spurred on further action in the subcontinent.  The Gothic government, for its part, took an immediate interest in the little principality of Orissa, strategically wedged between Andhra, Gondwana and Bulgarian Bengal. If Orissa could be secured for Gothia, then the Goths had a good shot at expanding their influence across eastern India and becoming a key fulcrum in the balance of power between the British and Bulgarians in the region.  Gothic efforts to secure their influence in Orissa were blatantly obvious to everyone, and Gothia's standing suffered due to its transparent scramble for territory.  Not that this stopped the Goths from continuing to plan. By the autumn of 1877, the Gothic fleet was ready and marines were awaiting orders.  And on October 28th, 1877, citing an obscure incident between a European merchant and a local official, the Gothic invasion of Orissa began.  To the surprise of the government's supporters, not everyone in the republic was enthusiastic about the war. Socialists in particular spoke out against the war, decrying it as a war for “moneyed interests” and claiming that Orissans would be used to simply undercut the power of Gothic labor. Needless to say, the liberal government was not happy. A message had to be sent.  Just ten days after the anti-war strike, an incident near the border gave the government the opportunity they wanted to set an example. Josép Heuvel- formerly Jozef before his home in Toxandria was annexed- had been a major agitator along the Rhine for unionization and socialist movements. Caught in suspicious circumstances, the government hastened his trial and ensured he was given the death sentence. A blunt message was sent, to be sure, but the government was sure that that was the end of it.  Following start of the Orissan campaign, still ongoing, and the Heuvel trial, Jehan Bursiac, Gothia's liberal leader for the better part of a decade, announced his retirement on January 14th, 1878, citing health concerns. His replacement, still from liberal circles, was Ricard Custurarius, a former general, Minister of War, and a veteran of the Revolution of 1863. Custurarius vowed to preserve the republic and maintain order in the country, vows which pleased liberals and conservatives alike but alarmed the socialists.  Abroad, Custurarius' stern new government saw the Orissan campaign come to a swift end with the ultimate defeat of the Orissan army at Cuttack on January 20th, 1878.  Although the Orissan army was defeated, it took three more months for the Goths to complete their campaign of pacification, and so the annexation of Orissa only became official on April 12th.  Victory in Orissa was overshadowed by domestic scandal. The Heuvel Affair, thought neatly concluded, was reopened with the revelation that the Ministry of War, under the direction of Ricard Custurarius, had not only intervened in the case to ensure the conviction of the Franco-Gothic socialist, but had actively been involved in obscuring the identity of the real perpetrator of the murder Heuvel had been accused of committing.  The country quickly split into Heuvelists and Anti-Heuvelists, those who thought Josép Heuvel had been wronged and those who continued to condemn the activist. Passions were stoked when Heuvel's conviction was held up in the Court of Appeals, and by the end of the year newspapers across the country reported (both lightheartedly and seriously) about political discussions that ended with fistfights between Heuvelists and Anti-Heuvelists.  Tensions also continued to build up internationally, as Jerusalem and Gothia continued to contest the Ubangi-Shari region in central Africa. Neither side refused to retract their claims, and both countries continued to build outposts and forts increasingly close to each other.  In this atmosphere of heightened nationalism, frontier areas such as the old city of Maiança, a town taken from Gothonia decades earlier, began to rally to the Gothic flag. Old particularism among conservatives and liberals alike was beginning to give way to bigger visions of united fatherlands and victorious nations.  Nationalism was further stoked by colonial victory in Africa; in January of 1879, in the face of a near-crisis, the Kingdom of Jerusalem finally abandoned its outposts in Ubangi-Shari, letting Gothia assert control over the whole region.  It was only in 1879, four years after the beginning of its war with Carantania, that Verona finally agreed to cede the disputed enclave of Tirolis to the Carantanians. Although this was a war that Gothia had scarcely participated in, its involvement in the peace talks gave the government a small boost in prestige all the same.  While Gothia had been preoccupied with the Ubangi-Shari question and Alpine affairs, however, other European powers continued to build up their power elsewhere. Britannia in particular continued to focus on Gujarat, working hard to establish further footholds in India.  By the autumn of 1879, the British had invaded Gujarat, seeking to gain a concession around the port city of Bombay.  In the wake of the Heuvel affair, friction between labor and the government continued to escalate. At-will firing of anyone suspected of being a socialist grew more common as the 1880s dawned, and every confrontation between unions and bosses became a more and more of do-or-die situation, with neither side backing down and disputes turning into physical confrontations.  As the liberals fought against the left, the right began to soften. The old Royalist movement was finally eclipsed in 1880 by the new Partit Conservador, an avowedly conservative party which nonetheless fully reconciled itself with the republican order. While the old royalists had been supported by the declining aristocracy and officer class, the new conservatives were supported by capitalists and more right-leaning members of the bourgeoisie.  The greatest expression of these tensions was the Great Strike of 1880. Starting in the railyards of Liyun, the strike quickly turned into a general one among most major industries surrounding the capital. A new newspaper, Indavant, breathlessly reported on the disturbances with a sympathetic view of the strikers and an almost palpable hatred of the police. The government hesitated to crack down on the writers of Indavant directly, but tried their best to harass the paper's writers.  “The police are following us,” whispered young Evaric Delfidi to the man next to him. Without breaking his stride, the older man looked back to see two uniformed men in greatcoats ungracefully work their way through the Liyun streetside crowds to keep up with them. The man gave a crooked smile. “I feel flattered. Come on, Evaric, you said the steelworkers were north of here?” Evaric continued to stare at the police behind him as they walked. “Uh-huh, Mister Rostanh. They're refusing to supply rolled steel to the Baudoïn locomotive works while that place keeps hiring scabs to replace its strikers.” “Please, just call me Marc. And don't mind them until they pull out their clubs, would you? Their eyes can't hurt us. All I want to do is interview a few men for a paper anyways, then I'll be out of their hair.” The reporter and the teenager continued to the north side of the city, among the brick-walled mills that lined the west bank of the Rhone. The two policemen followed them, bumbling into pedestrians several times along the way. They approached a vast factory with no smoke billowing from its chimneys. The colored bricks above the main gate read PEYRREMOND IRON WORKS, but below that a strip of red fabric pinned to the wall was emblazoned with the words “STEELWORKERS LOCAL 1-8”. Marc turned to Evaric. “Thank you for being a good guide for a country bumpkin like me,” he chuckled, “but now I need to take care of business with the men here.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out some change. “Why don't you take a carriage home to be safe? I'm sure your mother would appreciate it.” “Don't have a mother,” Evaric muttered. Marc frowned. “Sorry, what?” “Don't have a mother,” Evaric glumly repeated. “She's been in prison for years now.” Marc paled. “Surely... surely you stay with someone?” “Aunt Romula's supposed to take care of me, but she doesn't even notice when I'm gone.” The reporter frowned again, and sighed. “Alright, look. I could still use some help navigating this town after this interview. Stay here, and when I'm done inside, come with me.” An hour later, Marc emerged to find Evaric staring intently across the street. “Evaric, what's... what's happening?” The teen nodded towards two men standing by a barrel, smoking cigarettes. “The policemen changed out of their uniforms. That's them, there.” A mischievous glint struck Marc's eye. “Is that so? I bet they'll follow us again. Come on, Evaric, we have a couple places we need to go.” And with that, Marc set off southward again, Evaric chasing after him after a moment's delay. “They are following us,” he hissed after a few minutes walking. Marc chuckled. “What's so funny?” Evaric asked, confused. Marc pointed ahead to an alehouse. “See that place? The owner and I had a... disagreement the other day. Now, watch this.” He pulled out a notebook and pen. Peering over, Evaric could see him write 'THE COMMITTEE HAS DECIDED ALL IS FORGIVEN. WE THANK YOU FOR YOUR HELP' and stuff the note in his pocket. “Who's the 'Committee'?” Evaric was confused again. Marc grinned. “There is no 'Committee', but they-” he jerked his head back towards the police tailing them- “don't know that.” Evaric remained confused until he watched through a window as Marc walked into the pub, handed the note to the man behind the bar, shook his hand, and left before the bartender could react. Evaric turned back, and saw the police also watching Marc. One of them seemed to point at the bartender inside while the other furiously jotted something down. After a moment, realization dawned on Evaric, and a grin crept across his face. As he and Marc continued down the road, he couldn't help but look back at the alehouse one more time. Sure enough, both policemen were walking into the pub with scowls on their faces. Evaric laughed. A quarter of an hour later, Evaric spotted the policemen tailing them again. He elbowed Marc. “They're back.” “So soon? My, they're getting efficient,” the reporter chuckled. He slowed his pace down, and a thoughtful look flashed across his face before settling into an impish grin. “You know,” Marc said, turning around, “there's one more interview I'd like to do for this strike story.” Evaric had not even finished uttering a shocked “what” before Marc began walking straight towards the police. The officers tried to look nonchalant, but the reporter was having none of it. “Gentlemen,” he practically bellowed, “it's a pleasure to happen across you two. The name's Marc Rostanh, writer for Indavant, but I'm sure you know that already.” He stuck his hand out. The officers looked baffled. Out of sheer instinct, one of them reached out and shook Marc's hand. “The name's Courtés,” he said, “but you can call me- say, wait a moment!” He recoiled from Marc's grip and reached for something in his coat. Marc raised his hands and laughed. “Officers, please! I know causing trouble won't do me any good. All I want to do is talk a little. I assume you know I'm writing about the strikes, yes?” Officer Courtés and his partner both nodded slowly. “Talking to those steelworkers only gives me one side of the story. I want to hear your take, if you have the time.” Courtés' eyes widened. After a moment, he began to speak slowly. “Well,” he began- and was interrupted by the rattle of a wagon rolling by on the cobblestone street. Before he could resume his answer, Marc chuckled and clapped his hands together. “Forgive me, forgive me! I think perhaps the open street is not the best place for an interview like this. My assistant here-” Marc finally gestured towards Evaric- “comes from here, but I suspect he does not know the sorts of places that would be conductive towards a friendly chat. Do you fine officers know of any good coffeehouses around? It'll be my treat.” Courtés brightened. “I know just the place!” he said cheerily. He turned to his partner. “Vergier's is up a few blocks, right? Right.” He turned back to Marc. “I do know just the place.” The policemen gestured to the reporter and Evaric. “Follow us!”   With unrest and suppression bubbling at home, Gothia entered the elections of 1880 tense and wary. Liberals did not trust socialists, socialists did not trust liberals, and conservatives quietly tried to present themselves as a better option than them both.  Strengthening the socialists' hand, a labor scandal made waves across Gothia in the late summer of 1880, as a young girl working in one of the Rhenish mines died in a mining accident. The plight of the workers, and particularly the continued use of child labor, enraged citizens across the country.  While the socialists attacked the liberals from the left, the right also enjoyed a resurgence, with conservative voices taking the opportunity to attack the liberals for “letting the flower of Gothia” perish in the mines and putting “money ahead of the nation”.  Despite this surge, the conservatives won only a sad 5% of the vote between the Partit Conservador and the reactionary Lèga Imperial. The Partit Socialista, which had won only 15% of the vote in 1876, more than doubled their vote shared in 1881. Conservatives, it seemed were either staying home or flocking to the nationalist Union Liberal, while old left-liberals were beginning to break with the Union Liberal to support the Partit Socialista. The country was politically shifting leftward, but it was also rapidly polarizing. New movements were taking root, and unrest, although kept in check for the time being, was rapidly rising.  Who knew where Gothia would be five years later? For that matter, who knew where Gothia would be in six months? World map, January 1st, 1881

|

|

|

|

Anarchists taking the place of fascists...? Spicy.

|

|

|

|

It's always a treat to see this LP update! I'm curious to see how these new political ideology mods you've put in will change things.

|

|

|

|

GunnerJ posted:Anarchists taking the place of fascists...? Spicy.

|

|

|

|

You know it's been so long that I've forgotten. Why does our flag have a chicken on it?

|

|

|

|

The thuggish guildmasters that hold Liyun hostage prove their barbarity and cruelty over and over again! Why must we suffer this? Why must fair Gothia weep in silence as this bloody-handed traitor and his cabal squat on the throne? It is not just Gothia, though- all the world seems to be falling to likes of these beasts! The God-ordained Order is falling, and now we see the results: men and women going mad, purposeless and yearning. We can heal the world, we must! But where to find a Triarius?

|

|

|

|

Funky Valentine posted:Why does our flag have a chicken on it?

|

|

|

|

If we dont go anarchist I riot in thread

|

|

|

|

Ofaloaf posted:Fascism's still in the mod, I just changed its color to brown and it doesn't trigger until 1905 or thereabouts, I think. Anarchism's a straight-up addition. Oh, neat!

|

|

|

|

Ofaloaf posted:Gothia controls Gaul. The rooster-Gaulish people/gallus-Gallus wordplay goes back to the time of Suetonius, at least. The rooster also was an occasional republican symbol, iirc

|

|

|

|

ThatBasqueGuy posted:If we dont go anarchist I riot in thread We're definitely edging towards Revolution/Civil War with the sides largely being Authoritarian(?) Liberals versus Socialists.

|

|

|

|

Xelkelvos posted:We're definitely edging towards Revolution/Civil War with the sides largely being Authoritarian(?) Liberals versus Socialists. Meanwhile, that chunk of ground that the Franks lost'll probably give them some fashy issues soon...and if not then who knows what the hell's gonna happen to that mixed monarchy/communist system they've got going

|

|

|

|

Beepity Boop posted:Meanwhile, that chunk of ground that the Franks lost'll probably give them some fashy issues soon...and if not then who knows what the hell's gonna happen to that mixed monarchy/communist system they've got going Juche maybe?

|

|

|

|

Beepity Boop posted:Meanwhile, that chunk of ground that the Franks lost'll probably give them some fashy issues soon...and if not then who knows what the hell's gonna happen to that mixed monarchy/communist system they've got going Byzlp has monarcho-communism. Well, in a manner of speaking.

|

|

|

|

The Franks will go full Al-Andalus. E: also real life has those Communist Carlists in Spain

|

|

|

|

Mladorossi Francie.

|

|

|

|

I suspect Huevel is going to be a persistent rallying cry for Franche re-conquest.

|

|

|

|

Vaig somiar que vaig veure Josép Heuvel ahir a la nit...

|

|

|

|

Xelkelvos posted:We're definitely edging towards Revolution/Civil War with the sides largely being Authoritarian(?) Liberals versus Socialists. So is Gothia OTL Russia, Spain or Germany?

|

|

|

|

Trains?

|

|

|

|

Ofa is obviously hard at work designing the trains for Vicky 3

|

|

|

|

Crazycryodude posted:Ofa is obviously hard at work designing the trains for Vicky 3 There will never be a Vicky 3.

|

|

|

|

Please. He is obviously working on Vicky 4.

|

|

|

|

Technowolf posted:There will never be a Vicky 3. https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=1117968050

|

|

|

|

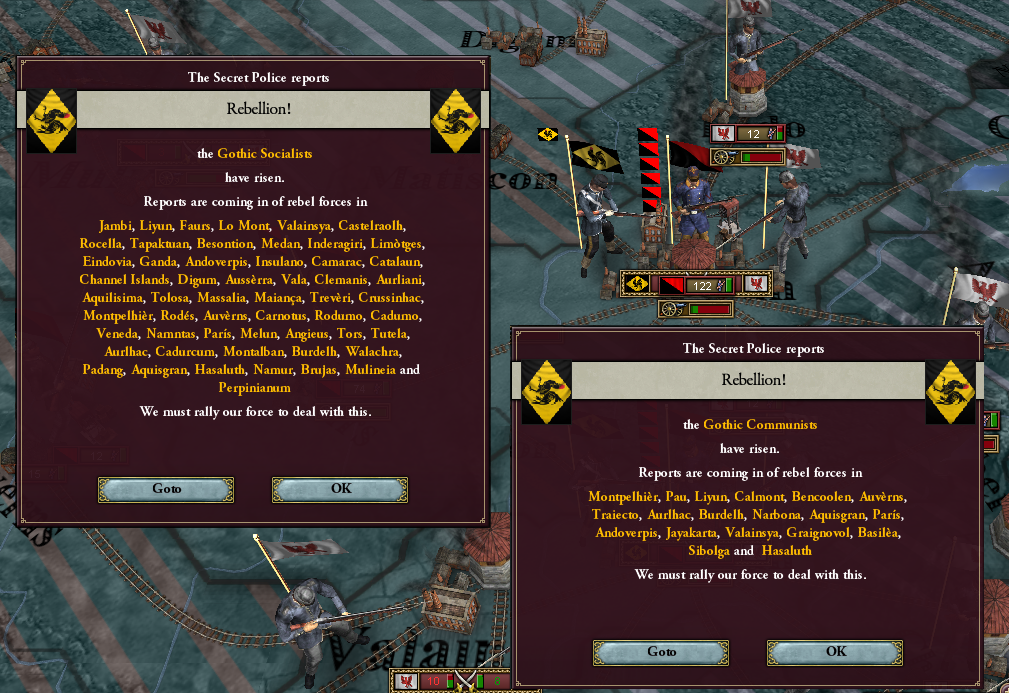

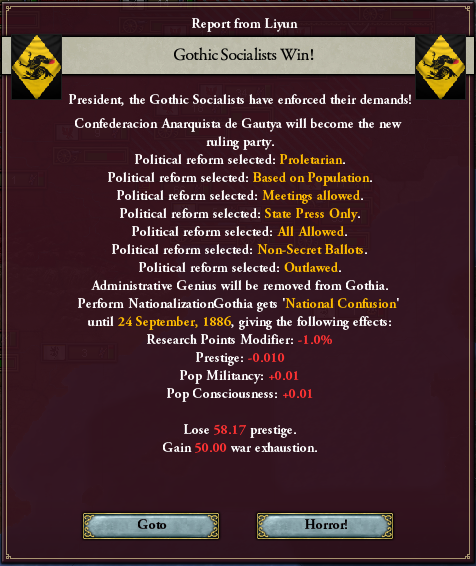

Chapter 82: Let's Wear Black 1881-1885 Two decades of republican government had lead to an entrenched adherence to liberal orthodoxy among the elites of Gothia; this increasing rigidity sent the country into a crisis that the liberal government, like the monarchists of twenty years earlier, were unable to politically or militarily resolve.  Gothia in the early 1880s appeared to be in good spirits; the government had, since the Revolution of '63, retaken the territories lost by the preceding monarchy to the Franks and then some. It had reestablished itself as one of the preeminent powers of Europe and the globe, alongside the likes of Britannia, Thrace, and Bulgaria to the east.  Domestically, the liberals had fulfilled their ideological promises of political liberty, but had gone no further. While every Gothic citizen had access to the ballot box and – on paper at least – an equal voice in government, the liberals believed that citizens' welfare was something that could only be addressed on an individual level, and had steadfastly refused to pursue 'materialist' policies like health care and industrial regulations.  Although the Union Liberal - the main liberal party in the government – refused to address 'materialist' policies, there was a growing outcry for new social policies among the increasingly politically-conscious citizenry. Movements proliferated and grew each year that the Union Liberal refused to budge on the 'materialist' issue, and left-wing parties were rapidly gaining supporters.  Beyond Europe, Gothia had recovered from the loss of its New World colonies and created its own sphere of influence in Sub-Saharan Africa, establishing a string of potent colonies across the continent. There, it rubbed shoulders with Britannia, along with the southern frontiers of the venerable crusader state of Jerusalem and the vast and Christian kingdom of Mali.  Although Africa itself was largely claimed by the major powers by the 1880s, the Pacific still offered some opportunities. Easter Island, never formally owned by any state and heavily depopulated by disease and repeated raids by colonial enslavers, was officially claimed by Gothia in 1881, and construction almost immediately began on a port and coaling station there. Colonial officials were pleased to announce that construction could be sped up by the use of local materials for fill on the wharves and moles.  The liberals' main concern was the preservation of defensive alliances spanning Europe. The two most important relationships were with the North African state of Mauretania, which controlled a considerable chunk of Hispania including the Pyrenees border with Gothia, and with Sorbia, which bordered the hostile Franks to their east. The Norwegian alliance was welcomed, but not deemed a high priority- the main priority was to either secure relationships which protected borders or posed a threat to those that threatened Gothia's borders.  These foreign policies did nothing to mollify growing domestic unrest. While the liberal government reinforced its treaties with Sorbia, a strike in Gothia Toxandria went sour and exploded into riots and uprisings on October 11th, 1881.  While widespread, the strikers did not have the equipment nor organization to face army regulars head-on, and in a series of bloody encounters the uprising was rapidly squashed.  By the start of December, the last holdouts had been arrested and the emergency was deemed resolved. Liberals affected a blasé attitude; riots and uprisings had happened before, and this had been no different.  Relaxed disregard for domestic unrest was bolstered by international developments; efforts by the likes of the Armenian Kingdom of Iberia to secure an alliance with Gothia - which was accepted - only reinforced the view that Gothia was on a fundamentally sound footing, since it appeared that even critical foreign observers could sense nothing amiss.  Further overconfidence came from the Arabian Crisis of 1882. Unrest in Jerusalemite Arabia once again boiled over, and the Arab independence movement made a concerted effort to organize itself and gain international recognition.  Jerusalem approached Gothia for aid, while Britannia swore its support for the Arabian movement. The crisis was rapidly escalating into an international struggle.  The flow of diplomacy was not on Britannia's side, however. Over the course of the summer of 1882, the major players in European diplomacy began rallying to Jerusalem's side. Even the Italian kingdom of Romania, a traditional enemy of Gothia, decided it would rather back Jerusalem rather than Britannia and the Arabian movement.  Deciding to move from its fortuitous position before any remaining powers decided to back the Arabs, the Gothic government offered to leave things alone if Britannia just dropped the whole issue. Although this solution satisfied no nationalists in either country, the offer was accepted, and the Arabian Crisis of 1882 became the latest in a string of unsuccessful efforts for Arabia to gain independence for itself.  Dissatisfaction with the deal in Gothia dissipated when strikes hit Britannia that December, and observers watched with glee as the island republic was consumed by revolution yet again.  Even when Britannia actually fell to the revolutionaries and a socialist republic was declared, few in Gothia considered the potentially alarming precedent of a liberal republic suddenly collapsing from the smallest setback in policy. Gothic liberals had had to tackle domestic unrest before just fine, and they'd be able to do it again. Perhaps that had been true in the past, but the liberal government's critics were growing in number and militancy day after day, month after month. Police reports were becoming more alarmist over the course of 1883, even as the Union Liberal dismissed concerns and focused instead on celebrating the 20th anniversary of their own revolution.  In the autumn of 1883, tensions reached a boiling point once again. The revolutionary strikers of two years prior were resuming their efforts to agitate and organize, and the state finally, belatedly began to respond with some heavyhanded measures.  In this tense atmosphere, the Gothic government made its first mistake: it agreed to support the Mauretanian invasion of Byzacena.  The Mauretanian army turned out to be surprisingly under-equipped and ill-prepared for the war, and suffered a series of humiliating defeats from the onset. Expeditionary forces from Gothia were necessary, if the Goths wanted to preserve their good relations with Mauretania and thereby preserve peace along their mutual border at the Pyrenees.  To the Goths' credit, the army corps they sent to North Africa performed admirably. Mauretanian fortunes were turned around after the Goths obliterated one of the major Byzacenan armies outside the old Roman town of Constantina, and Gothic troops then helped pacify hostile Numidian garrisons to protect the Mauretanian eastern front.  It was thus while a considerable part of the Gothic army was overseas that the socialists rose up again in the middle of 1884. Like in 1881, it began with a series of strikes, but these had remained peaceful only as long as the government had not attempted to suppress them- the strikers had learned from 1881 and reacted the moment arms began being used against them.  While the rising was larger than the Uprising of 1881, Gothic army units were still better-equipped than their revolutionary opponents, and it seemed likely that 1884 would play out like a bloodier, drawn-out version of 1881. Many would die, but the liberals would emerge victorious again.  It likely would have turned out that way, had Francië not declared war on July 19th, 1884. Yet again, the disputed Rhenish territories had proven to be a rallying cry, and Gothia's obvious domestic problems provided the best chance the Franks had to strike and win.  To the shock of Gothic politicians and the public, Gothia's web of alliances utterly collapsed in the face of the Frankish declaration. With the country imploding while also being invaded, no other nation expressed willingness to immediately jump to Gothia's aid.  Expeditionary forces in North Africa were hurriedly recalled to deal with the emergency. Mauretania's refusal to assist Gothia's defense meant that Gothic troops could no longer be spared anywhere other than the metropole.   Belatedly, Mauretania realized its own diplomatic mistake as Gothia signed its own peace with Byzacena and withdrew its troops. Weeks after their refusal to take up the Gothic call to arms, the Mauretanians offered to reestablish their alliance.  Mauretania was thus belatedly drawn into war with the Franks in August 1884, and its involvement began to draw back many of Gothia's other allies, such as Norway, who had initially hesitated in July.  Gothic strategy in July and August, chaotic as it was, emphasized consolidating whatever forces were available, and rallying around the capital. If enough men were massed, it was hoped, enemy forces would not dare approach the capital city. Most major battles involved Gothic troops fighting through or being intercepted by opposing forces on their way to Liyun.  There were some surprises during these days of crisis- General Custurarius successfully led a division of raw conscripts to victory over Frankish-allied Romanian soldiers at the Battle of Ledo on September 10th, astonishing onlookers on both sides of the war.  Another Frankish army was wiped entirely by General Amalius, a supposed descendant of the ancient Amaling kings, at Brussèlas on September 26th. Between Custuarius and Amalius' victories, it seemed possible that Gothia might yet survive this onslaught.  On November 11th, another wave of strikes and socialist uprisings hit the country. While the army had mostly managed to bloodily suppress the July Rising, nothing had been done to address any of the underlying issues, and the military's losses during the Frankish invasion only weakened the government's position over the autumn.  As the country burned, election season approached. The government, either through ideological commitment or inability to effectively do anything else, did not attempt to postpone the vote or suppress any voices.  War dominated the election; fighting spanned Europe, as Sorbian and later Norwegian intervention opened up an eastern front for the Franks to concern themselves with, while the tired Gothic armies struggled to hold the line in the west. Millions were dying across the continent.  In this tense atmosphere, the left-wing uprising gained traction, and additional uprisings in early March of 1885 strengthened the rebel position to the point that they could now seriously march on the capital themselves. At the same time, a stream of government documents began flowing out of the city, as officials began fleeing westward to the Atlantic-facing port town of Burdelh. Liyun, the venerable capital, was left to the growing mob.   Mustered conscripts were no longer enough to fight the revolutionaries; they were winning battles against the army and further reinforcing their position as they slowly took over the capital, district by district.  Ironically, Socialists won the national elections in 1885 just as the revolutionaries completed their takeover of Liyun. The liberals had given up all pretenses of campaigning for the election as they fled the embattled city, leaving the contest to the socialist coalition on the one side, highly mobilized when their supporters weren't already bearing arms, and the still-unpopular conservative monarchists on the other.  The Socialist victory did not matter much in the long run. Just two months later, on September 24th, 1885, revolutionaries broke through the last defenses in the capital, claiming control of the Bank of Gothia's major gold reserves, and proclaimed the end of the bourgeois Gothic Republic.  Francië and its allies were surprised by the development, but had also grown exhausted from the bloody conflict as well. Popular sentiment across Europe, and even within their own nations, was slowly shifting to the Gothic side of the conflict. The cold-hearted abandonment of the country by its allies, the call for national conscripts, and the overthrow of the old government had helped recast the Gothic nation in the eyes of neutral observers, as one Frankish general put it, “as a heroic-hearted people that against overwhelming odds is defending its homeland in honorable fight,” while the Franks themselves were more and more seen as “the arrogant victors, no longer content with reconquest of a lost land but fain to bring about his foe's utter ruin.” Militarily, with the revolutionaries now in control of Gothia, there was no major unrest in the country's interior to split Gothic forces, and the Frankish alliance, led by Bulgarian negotiators, decided to settle for the status quo ante bellum rather than risk the tides of war and diplomacy swinging against them.  On October 2nd, 1885, the act was made official. The Gothic Republic was no more, and a new government, the Confederated Communes of the Workers (or Comunas Confederats dels Trabalhars, the C.C.T.) would rise from the ashes.  The world, October 2nd, 1885

Ofaloaf fucked around with this message at 17:50 on Dec 12, 2021 |

|

|

|

The world revolution marches on! I am amazed in a very pleasant way to see this back.

|

|

|

|

It's back! It's back!!! O glorious day, it's back! And what an interesting note to return on. Things keep happening.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 19, 2024 16:41 |

|

Yeah, this updates very rarely, but every update is great. I think that's a good trade-off.

|

|

|