|

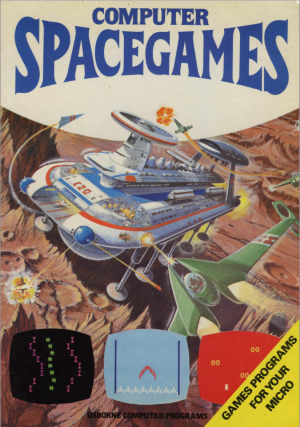

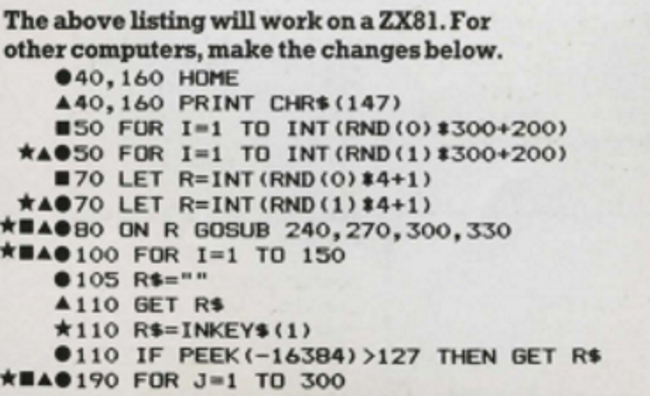

Being A Participation Let's Play In Several Parts, Also Known As "Let's Go Back To BASICs!" When I was a wee lad, creating games was all about cheating. Or, y'know, writing in BBC Basic and changing numbers around in the hope that the games you made somehow became fair. Or that calling the DRAW command to make something truly nice didn't take forever (I have never found a good solution to this.) But BASIC still has a place in my heart, because of the attitude to educating in it. Every time I open a game programming book, it's either peppered with poo poo that the writer expects you to already know, or uses specialist terms. Back in the day, though, there was a major push for computer literacy by the British Broadcasting Corporation, and the BBC Micro was born. A little bit later, a publishing group called Usborne-Hayes (Now just Usborne) created a series of educational books on... Well, programming for kids. ...They're super accessible, and it's not just because they're using BASIC. There's a machine code one in there too, and that, also, is pretty accessible (Although it is the weakest in the series, in terms of what it actually teaches you) Okay, So... An Ancient Language On An 8 Bit System... Why Should I Care Today? Because this Let's Play isn't just about the language... It's about how we forget to make teaching poo poo accessible. It's about game design history. And, just as importantly, it's about showing you that yes, you can have fun with limitations. And trying to hack this poo poo for different architecture. And the fact that this isn't a new problem. In short, me (and hopefully some buddies) will be edjumitainmenting you. And hopefully, some of you goons will write your own tutorials for other languages and engines that learn the lessons these old books have to teach. Oh, and folks still play with BASIC to this day, on all sorts of systems. In fact, here's a music video coded... On an Apple II. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gxe40xXQKko). The creator even released the source code: here (Thanks to InternetJanitor for that!) Wait, Edjumitainment? Does That Mean You'll Actually Teach Us Stuff? Oh yeah! In fact, I'll be setting little class exercises! If you want to play along, you can use BeebEM (BE link), and save your program to a disk image you've made. Don't worry, because BASIC programs are pretty drat small, you can fit loads of them on the same disc! As an example, here's a copy of the programs in Computer Space Games in Single Sided Disk Format, typed out by yours truly, with the other coursebooks we'll be using to follow (Computer Battle Games, Creepy Games [found on the Internet Archive], Write Your Own Adventure Programs, and Write Your Own Fantasy Games BeebEM is a beautiful thing. It can emulate the main BBC models (Imperfectly, but it can do it), and, for the majority of this LP, we'll be using the bog-standard Model B (Something like 16K of RAM for all practical intents and purposes.) So, once you're in BeebEM, here's what you do. 1) Type in your program. This will, I guarantee, be the most frustrating part if you haven't spent some planning time. 2) File --> New Disc 0. You get to name it. 3) Type SAVE “[progname, no more than 7 letters]”, hit enter. 4) If you then go EDIT -> Export Files From Disc, you should see your BASIC Program listed, along with hex numbers that basically tell you where it is on disc, and how big it is (in 8 bit "blocks") 5) Put the disk somewhere I can reach it, and tell me it's there! 6) You can even put multiple programs on one disk! Although by the end of the thread, you may need another one. If you want to check what's on the disc, type “*CAT” and hit enter. It'll chug a little, then show you what's on the disc. LOAD “[progname]” loads it, and then RUN runs the program (or just CH. "[progname]"...) Simple! And for those who don't particularly want entertainment? I'll be picking certain BBC Games to have a brief play of, to give you some idea of the variety of games that existed on the system. Also, I will be playing some of the games on the discs. Oh, I'm Not Much Of A Programmer Anyone can be a programmer. Seriously. The main obstacles aren't as much in the languages/engines and their quirks themselves (Although they do factor in, as we'll see), but in how we teach this kind of thing. We don't teach in terms of "What Do You Want To Do?" and "Adapt What You Know", so much as "Here are some programs, and how they work. Now check the reference guide for more ideas." Once you understand the basics of how a language works, you really can do amazing things from day 1. The key, as we'll see, is properly working out what you want to do first. Can I Use Another 8-Bit System? While the Beeb is preferable, and I will go into porting between different BASICs later, I can keep up, so if you're more comfortable with, say, a Speccy or an Apple, then sure! Not all the books, however, will help you as much as you'd like. For example, the C64 may not do everything the way other Commodore models did, so it's important to read the reference book for your chosen system! The books have conversion keys, and this is what will be used for the main books. When you see one of these, that means you'll want to check the bottom of the listing to see what changes you need to make. Some of them, you'll get quite used to (Such as RND):  Because I know some folks want to use other than the Beeb, here's the conversion key Now... Let's get started!  ...Er... Well, at least that reminds me of a tune (Thanks, Great Joe!) that somewhat fits the situation we're in? Contents and Stuff Part 0.5 - Know The BASICs. Part 1 - Guessing Games ... IN SPAAAAACE!!! Part 1.5 - Exercise For The Class 1! Part 2 - Creating A Shooting Gallery Via Text EXTRA CREDIT This is where nice thread contributions from the class have come in! BABA FEKK - A Bounty Hunting Game By Tiggum Paul.Power spreads the good word of Usborne, who have nicely released the set books.

JamieTheD fucked around with this message at 18:59 on Feb 24, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 25, 2024 08:40 |

|

Part 0.5 – Know The BASICs Not actually a bad way to learn! There are good ways to learn BASIC, and bad ways to learn BASIC, just as with any tool or language out there. For example, I could have asked you to make a Tic-Tac-Toe game using just PRINT, IF (AND/OR) – THEN, LET, GOTO, and INPUT. Even if I explained these well, you would be tearing your hair out and calling me very rude names, because, even if they are the absolute basics you need to make a game, there is a reason there are more commands in BASIC, and at least part of that is to get around kludge. But before we can do any of this, we have to know how BASIC works. Imagine a list. If you don't have any numbers on this list, things will only be done as you write them. For example, we could type “LET B=1” … And B will be one until we change it. Even though we can use that B for other commands now, it's pretty loving useless on its own, and isn't really a program. It's certainly not a game! So we need a way of making sure the list will only run when we want it to. This is where numbered lines come in. BASIC runs on numbered lines, and the BBC will keep those numbered lines in its somewhat limited memory until either it can't keep any more (At which point it will tell you), until you type “NEW” and hit enter (In which case, it'll erase the whole program), or until you reset the BBC (Which resets the memory as its first step.) The BBC understands numbered lines, in its way, knowing that if you've put a number before a command, it's to save it to that numbered spot, and, when you type “RUN”, and hit ENTER, it'll go down those lines, one at a time, until it's done everything you asked it to, in the order you asked it to. This is what's known as a procedural language. So let's build a simple program, to show you how it works. At least on 8-bit systems. Later versions, such as QuickBASIC for DOS, would allow you to write without numbers, and modern BASICs, like BlitzBASIC, DarkBASIC, and BBC Basic For Windows, are object oriented... 5 CLS 10 PRINT “HELLO WORLD!” 20 LET DAY$=”TUESDAY” 30 INPUT “WHAT'S TODAY AGAIN? “;WOTDAY$ 40 IF WOTDAY$<>”TUESDAY” GOTO 70 50 PRINT “OH, GOOD, TODAY IS INDEED TUESDAY!” 60 END 70 PRINT “WAIT, TODAY IS “;WOTDAY$;”? CRAAAAAP!” This program has all the simplest stuff. PRINT prints stuff on screen, with the “;” meaning “Add this on the end without any spaces or tabs”, LET stores stuff in memory ($ on the end for text, no $ on the end for numbers), INPUT can either be used on its own (for just straight up asking for text or number input, same as LET), or doubles as a combo of PRINT and INPUT without the quotes, GOTO goes to a certain line in the code (Fun Fact: BBC BASIC, and indeed, all the other procedural types of BASIC, check what line to GOTO by counting all the way from the beginning of the code. So the later a GOTO is in your program, the longer it takes!), while END... Ends the program before it's meant to. You'll notice I didn't put an END at the end of the program, because, once it's finished with the program, it's back to single commands. You'll also notice two things: I didn't tell you about CLS (Clear Screen... Does what it says on the tin), and that the first line is the only one without a multiple of 10 being in the program listing. That's because it was standard practice to list the lines in multiples of 10, because you could then edit in 9 extra lines between each line, in case you wanted to add to the code without changing what you had. This convention will be used throughout, because it's useful. But I did say these are the absolute basics of making a game. Why did I say that? Because a game, at a bare minimum, tells you a situation (or shows you), asks for your input, and then does something based on the input (often refreshing the screen to do so.) Modern games, even simple ones, follow these rules... It's just that they partition things better (Thanks to Object Oriented Programming), and they do it more (Because even a simple mouse pointer requires its own rules to follow) By the end of this, you'll not only know enough BASIC to make something much classier, I'll also be showing you how the skills you're going to learn apply to games programming in general, and a little bit about changing attitudes in game design, for different values of “then” and “now”.

|

|

|

|

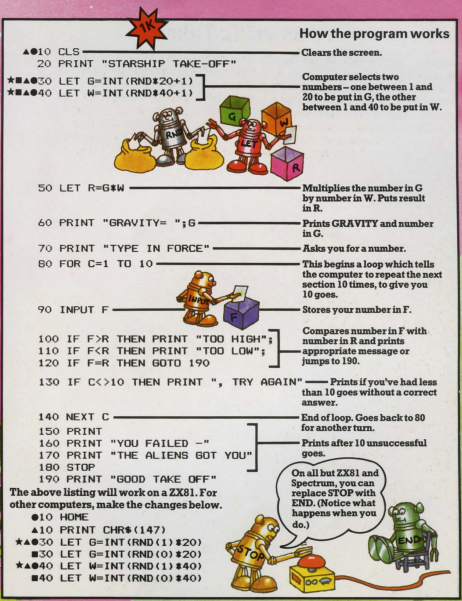

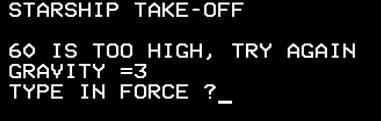

Part 1 – Guessing Games... IN SPAAAACE! Computer Space Games, released in the early 80s, is the first of the books we're going to visit. And it's going to tell us about many of the same things I told you in 0.5, but in a more practical and measured way. While another book in the series (Beginning BASIC) deals with individual commands, and what you can do with them, and the BBC User Guide has the skinny on all the BASIC commands, Computer Space Games is more like a cookbook: It spends a whole two pages saying: “Here are your programs, you'll have to type them in, remember that BASIC has some differences across different systems (Just remember your symbol and you'll be fine [ours is a star]), you can edit these to your heart's content [and we're going to], you will make mistakes [Because typing out a program is mind numbing at the best of times], and here's how to list and run your program once it's done. HAVE FUN!” There. That was nice and easy. And then it immediately launches into the programs. Here's our first. It's a guessing game. In fact, this, the next three or so games after it, and the majority of games in the book, are guessing games. They're nice and simple to program, you see. Let's take a look at the listing for this one.  EDIT: And the listing in text form, for ease of use. Thanks to Tiggum and RickVoid for noting this! Tiggum posted:It's an asterisk (*), for multiply. IIRC, the way it works is that RND generates a number between 0 and 1, so multiplying by a value and then converting to integer gives you a whole number between 0 and whatever value you chose, eg. if RND gives you 0.356 and you multiply by 20 you get 7.12, which rounds to 7. Now, you'll already have noticed the first nice thing about this book: It actually comments on the loving code (unlike many programmers you're going to meet). And, since it's procedural, we can literally go down this list to see what order it does things. So, let's examine that ourselves. First, it clears the screen. This is loving useful, and most of these programs don't do it enough. Seriously, when you see a screenshot of how this thing looks in play, it's kludgy as gently caress. But it's a First Game, and decent screen refresh is easy to do. So easy to do, in fact, that that's going to be our exercise for this update. You don't even need to show me a file, just post what lines you'd add/change to fix the problem you're going to see. Next, and most importantly, it a) Tells us what the game is called, and b) Sets the components of what we're going to be guessing. It does this using a shiny command I haven't talked about yet: RND, aka “Random Number Generator (Not clock based)” RN Jesus, as it is often known, is complicated stuff... But games programmers of the 80s didn't always appreciate how our good buddy RN Jesus worked, so they often used this instead of something more complicated. Put simply, it doesn't actually roll a dice or anything, with all that physics and micro interactions and other fun stuff that fucks with a “natural” random result, it generates a number based on the cycling of a list of numbers it keeps, making it pseudorandom. It's not really random, and sadly, it does have some bias, being a maximum of 2^48 possibilities with certain numbers appearing more often. However, if they're given the same data, at the same time, with the same maths applied to them, two different BBCs will spit out the same “random” sequence. Which is why it's really important, when making games, to craft your RN Jesus with love. But either way, we get a range of numbers between 0 (G=0 or W=0) and 800 (20 and 40 respectively) to guess. (EDIT: The er... 0 isn't actually intended behaviour, but a typo. It should be 1 and 800. I fell for this too.  ) )Except we're then told one half of the equation, and we start a FOR loop (More on that in a minute) to give us 10 guesses. It took me years to realise how important that first bit was, and when I did, I kicked myself, because 8 year old me genuinely thought “I have to get the right number in only 10 goes? But there's 800 of them!” ...Younger me was surprisingly dumb sometimes. You already know the smaller number (G), so what you're actually looking for is which multiple of that is the right one. And there's 40 multiples. It also tells us if we went too high or too low, so we can get to the right number in a maximum of 5 moves (20*G, move 10*G up or down, move 5*G up or down, move 2*G up or down, move 1*G up or down)  On my emulated runs of the program, the first time I run it, the gravity is always 8, and the answer is always 56 (YMMV on this one, because of variances between computers, but on a reset, without seeding, it should be the same number every time you reset, load, and run). The second time, the gravity is always 5, and the answer is always 50... So on, so forth. This is why taking care with your Random Number Generator is very important. In the case of the BBC, however, it's stupidly difficult to make a decent RNG (Although an OK one exists), and said RNG is biased (Some numbers appear in the register more often than others).  For those who are curious, the way to seed (“randomly” set) the RNG is by adding this line before the rest of the program. [variable letter/name you're not using]=RND(-RND(TIME)) ...It reseeds the RNG based on how long the BBC's been running. It won't make it completely unpredictable, but it will ensure there's another layer of pseudorandom you can't fully control in between you and confidently predicting the answer will always be 8 the first time you run it.  So now we talk about the FOR loop. The FOR loop is quite simple. You declare a variable to loop between (1 and whatever the gently caress you want the end to be, for basic loops), and the program goes down the line, executing instructions, until it gets to “NEXT [variable you declared]”. Then it goes all the way back, adding 1 to its counter, and repeats this until that counter hits the number you wanted it to. Then the program gets out of the loop. It's mostly used as either a timer or a counter for repetitive actions. No, you can't hang your BBC by changing the endpoint halfway through. But you can do other, clever things with FOR loops that are X to Y, instead of just 1 to X. We'll deal with that though, another time... Exercise For This Session: I want you to spice this program up. Just a little bit. Right now, it looks like this when you run it -  As the image title says: Kludgy... As... gently caress. And that's a bit cluttered. We don't want clutter, we just want three lines of text, maximum, on screen at any one time... A clear-ish screen, until the end. But we want to still know if we were too forceful or not. As mentioned, this is a post exercise, just post what lines you'd add/change/get rid of, and why you did it. 24 hours for this one.  Guessing Games On The Disks UHayesSpaceGams.SSD (More on the way!) STOFF - Starship Take Off (pp4-5 , Computer Space Games) LIFTOFF - Starship Take Off with time seeding IGGAMES – Intergalactic Games (pp6-7, Computer Space Games) EVALIEN – Evil Alien (pp 8-9, Computer Space Games) LANDER1 – Moon Lander (p12-13, Computer Space Games) MGALAC – Monsters of Galacticon (pp 14-15, Computer Space Games) TTRAVEL – Trip Into The Future (pp 20-21, Computer Space Games) Things You Can Possibly Do Later On With These. Add actual graphics (P. much all of them, but especially Evil Alien and InterGalactic Games) Add sound (Again, p. much all of them. We'll be dealing with SOUND later, because the books mostly gloss over it.) Random BBC Game: Repton (Superior Software, 1985) Vid Superior Software, still somehow around today, lived up to their name at the time as one of the premier publishers for the BBC and Acorn Electron, and Repton was one of their longest running franchises. While many can definitely criticise the first game as “Just a Boulderdash clone” (Despite the fact that Tim Tyler, the creator, wrote the game after seeing a review of Boulderdash, never having played it until after said criticisms came in.  ), later games in the series would gain their own identity, and not just because of the character of Repton himself, who, for an alien, got around a bit. Proof below: ), later games in the series would gain their own identity, and not just because of the character of Repton himself, who, for an alien, got around a bit. Proof below: But for now, the simplest game in the series. For simplification, Repton 2 was the only “single world” game in the series, and Repton 3's engine (And rules) were used for the majority of the series. Repton Infinity was a tool for making, essentially, your own Repton game. And yes, Repton is still around. JamieTheD fucked around with this message at 12:30 on Dec 11, 2015 |

|

|

|

reignofevil posted:I just barely eyeballed the code for a second but it looks like I would add "91 CLS" to clear the screen after the user has input some information but while still leaving what they should need to guess the number on their screen. A worthy quick guess, and this is indeed part of what can be done (Yes, there are multiple possible answers)... But it doesn't lead to all the information you need. If you 91 CLS, here's what gets shown on your second attempt onwards (Obviously, with "Too High" if you got it wrong.  Note the lack of Gravity, as PRINT [gravity] was outside the FOR loop. However, to identify that yes, the screen doesn't clear after every turn, while seemingly obvious, is important. Imagine that one program comprised of something like 600 lines of code, rather than the 19 it actually has, and you missed something that simple. BBC BASIC, unlike many later versions, doesn't really have commenting (EDIT: The longest single program in these books is the Silver Mountain adventure, at approximately 489 lines of code. Technically, the Adventure Program is longer, but is split into three separate programs, for memory reasons) Now, obviously, a thread takes time to get going, and I understand this. So this is being extended for 48 hours to give folks a proper chance. But this post has provided an important clue... The winning message is outside the loop, so are the losing message, the title (Eh, that one's unimportant for now), and the Gravity. Part 0.5 also has a useful extra in INPUT "[printed words]" [variable]. QwertySanchez posted:Man, I loved these books as a kid, and BASIC. Impressed all the kids at school with my programming skill on the lovely computers we had while out in the real world you could get windows 98. Played the poo poo out of Repton, too. I wish I could find the little comics that came with the later Repton games, because my god, distilled 80s. But yeah, for those outside the UK, the BBC Micro was still in schools in the late 90s. They were some sturdy fuckin' things. I'll be talking a little later on in the LP about both the good and the bad in the books, as they definitely embody design philosophies of the 80s. It wasn't until the late 80s/early 90s that game designers really started to stretch themselves, so to speak, although the money you could have made in programming back in the day was bloody silly. Another goon and I were going through, looking for a specific program of the 80s, and we found this: Writing for the Early UK Home Computing Mags. CTRL-F "£75" , and prepare to be shocked. For reference, that's almost £177 in today's money, for a SINCLAIR BASIC program for a magazine. As the thread continues, and thread-goers get more used to BBC BASIC and how it works, this will most likely become even more shocking. I know, when I read it, my reaction was "The gently caress? WHY DID NOBODY TELL ME THIS BACK THEN?!?"

JamieTheD fucked around with this message at 17:47 on Dec 10, 2015 |

|

|

|

[wakes up... looks at thread] Oh my! Right, discussion and data entry time, it seems! FredMSloniker posted:If we're more familiar with BASIC in another OS (for instance, the Commodore 64 I used as a youth), can we use that, or do I need to learn the Beeb to take part? While it's preferable to use the Beeb (Especially since a later post will have me converting to the good ol' C64 with its PEEK and POKE, and since the C64 just doesn't have quite the same limitations as the Beeb), I certainly wouldn't like folks not to be able to participate, so just lemme know which BASIC you're using in advance, and I'll try to keep up. And yeah, text adventures would definitely be the first things to come to mind for most of us younguns. I remember writing those looooong DATA statements, and will again before the thread is out.  As to the games being not so good, you are quite correct, they are nearly all text based, but they teach things fairly organically for most of the books, going from simple guessing games, to not so simple guessing games, shooting galleries (Our next subject, funnily enough), racers and reflex games (of a sort), to graphics of both kinds. My main criticism of the series is that it really doesn't go into SOUND very much, so I'm going to have to take up the slack there. The BBC's sound chip is not great (Certainly not on the level of the C64's SID, which people still play with today!), but it does have some potential, as we're going to see next time. As to the games being not so good, you are quite correct, they are nearly all text based, but they teach things fairly organically for most of the books, going from simple guessing games, to not so simple guessing games, shooting galleries (Our next subject, funnily enough), racers and reflex games (of a sort), to graphics of both kinds. My main criticism of the series is that it really doesn't go into SOUND very much, so I'm going to have to take up the slack there. The BBC's sound chip is not great (Certainly not on the level of the C64's SID, which people still play with today!), but it does have some potential, as we're going to see next time.  RickVoid posted:I can't read this fuckin' thing. It's too small, and too blurry to make out some of it. So before I can work on it, I need to get the base code down on something (I'm using Notepad) and it's just not working. Ah, that is indeed an issue, and I shall make sure to post original code, as Tiggum has so helpfully done! Any other suggestions to make the thread more accessible are gratefully accepted! Tiggum posted:It's an asterisk (*), for multiply. IIRC, the way it works is that RND generates a number between 0 and 1, so multiplying by a value and then converting to integer gives you a whole number between 0 and whatever value you chose, eg. if RND gives you 0.356 and you multiply by 20 you get 7.12, which rounds to 7. Now, small but important note here: Remember how I said there would be typos? I forgot this one for my own listing, but there is a reason there should be a +1 on the end of the INT(RND) in the brackets. Namely, that a small enough number here will get rounded down, leading to a thrust of 0... You can tell I fell for this typo myself, if you look in the main post.  Checking code, and both Tiggum and RickVoid have got pretty good answers, with Tiggum using Screen MODE a lil' bit early to give the game that good, chunky feel, earning a silver star. As Tiggum notes, however, the "Try again" will ne'er be seen, because the loop clears too quickly... ...However, another use for FOR loops has been mentioned in the thread (And, funnily enough, this second use is going to be the theme of the second and third updates), so, I'll give this one for free. code:So, it should be noted that there are multiple ways of doing things, even in these early stages, and happily, Tiggum and RickVoid have happened on a different way than what I was going to show. This is a good thing, because, this early on, unless you try really hard, there isn't really a bad way of doing things. It's also good to mention that MODE 1 is, technically, the "best" graphics mode, as, while the text is chunky, it doubles the actual pixel height compared to the other graphics MODE we'll be using, MODE 5. We'll be talking about the strangeness of how the BBC handles DRAW calls in about four updates, but suffice to say, graphics are definitely dealt with differently than text, and it's one of the BBC's more annoying quirks. Still got until 6PM tomorrow to explore things, but in the meantime, I'd like to thank everyone who's posting to the thread, as this definitely wouldn't be half as fun without your input! JamieTheD fucked around with this message at 09:19 on Dec 11, 2015 |

|

|

|

Polsy posted:Now that's a good reminder of how much computing power and/or language interpreters have advanced in 35 years, you'd have to try a lot harder than 600 to get a noticeable delay these days. Yeah, for comparison, the BBC Model B processor runs at an amazing... 2 MHz. An Intel 486 runs between 16 and 150 MHz. The ZX Spectrum runs at 3.5 MHz. And my current system has 6 independent cores, each running at around 4 GHz. We've come a long way. We'll be seeing some silly numbers when conversion time rolls around. Paul.Power posted:It may be worth noting that the star, square, triangle and circle mean "replace this line with something else if you're using something other than a ZX81". - the stars are for the BBC Micro and Electron, the triangles are for the Commodore VIC and PET (which are probably the closest thing to a 64 here?), the squares are TRS-80 and the circles are Apple. There's also S for Spectrum changes, although I guess this program didn't need any. Conversion chart is added to the OP, for ease of use.  As to changes, the major differences are in Data storage/retrieval, and how DRAW/User Defined ASCII symbols are handled. I... Honestly expect to get lynched when updates 4 and 5 roll around, because the... Somewhat unique way the Beeb handles drawing is... Well, you'll see when we get there. Suffice to say, this is as much an education that yes, sometimes odd decisions were made when making older systems.

|

|

|

|

reignofevil posted:I don't really have any other guesses right now but I am curious; how is this program dealing with bad input? Are letters just ruled out somehow? Sort of. The way it handles it without any help from you is this: If you're asking for a number, and you give it letters, it assumes you meant 0. If you asked for letters and you gave it numbers, it assumes the input is a text string. Since the game's only asking for a number, it's an assumed fail if you type text instead, although, now we've ruled out 0 being a number, a special case could be added where you would ask again if the answer you gave was "out of bounds" via an IF...OR statement (like IF N=0 OR F>800 THEN GOTO [ASK AGAIN]) , and other games in Computer Space Games do exactly that, most notably Space Mines, which won't let you spend more money than you have. Ruling out 0, in this case, would also rule out text inputs to a number request. Now, to be 100% clear, because I don't think I was: The replacement code actually has a typo in it that I'd not noticed (but fell for this once), and INT(RND(1)*20) would actually result in zero to 19, as the BBC always rounds down. That's what the +1 at the end is for. So, with the +1, the range is 1 to 20. Paul.Power posted:Yeah, INKEY$ is useful for stuff like that. I remember it being a thing in QBASIC, but couldn't remember if it was in older versions of the language as well. Looks like it is! Sadly, RickVoid's code isn't quite right. Specifically, it needs to be something along the lines of this: code:code:As to reading ahead, feel free! There's definitely no rules against it, and it's definitely worth looking at the more complex games to see how they handle things. For example, you would encounter a most useful thing if you want tidy code: The humble colon ( : ). This lil' feller, so long as you're aware there's a 248 character limit per line, allows you to concatenate any lines that would make sense running in order except for multiple IF statements. For IFs, we'd have to do the thing we usually do with IFs... IF X=Y THEN [Thing] ELSE (Sometimes with an IF of its own, but in the case of binary "Right/Wrong", you can just have a GOTO or other command.) So, for example, line 1-6 should be able to fit in one line with the colon between them, and if we had a FOR...NEXT loop on its lonesome without commands, it would make perfect sense to just put them together like this: code:What's this useful for? Mostly, I use it as a tool to break BASIC code into rough guides as to what each block does. It doesn't, as far as I know, make the program run any quicker, and it does, to be fair, look ugly as hell writing it down anywhere outside of MODE 0 (The most character heavy mode.) Still, it saves a lil' bit on typing.

|

|

|

|

FredMSloniker posted:So when's the next exercise go up? I admit, this one isn't grabbing me, mainly because I keep thinking gravity does not work that way rrrrrrgh Next class exercise will be tomorrow, but there'll be a post archiving everyone's efforts, plus showing you a third way to handle things (RickVoid and Tiggum have done one, while FredMSloniker decided to ditch the FOR loop entirely, going with a GOTO/Counter variable based approach) later today! I had thought about posting a little class note, as you'd see in primary schools of the 80s, with the Bronze/Silver/Gold stars, but I'll leave it up to the thread if we really want to do that. I know that, while it would thematically fit, it might lead to friction, and I like my threads to be as conflict free as possible.

|

|

|

|

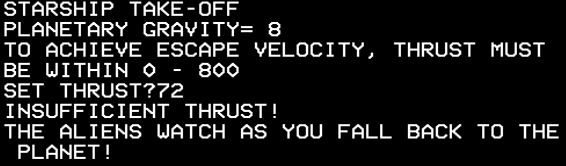

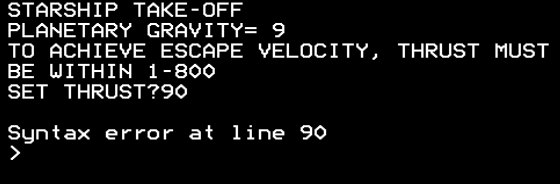

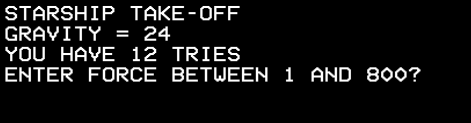

Update 1.5 – Exercise 1 Results Well, it's been an alright start so far, with folks gamely stepping up to the plate, and things being learned! Two out of the three main entries for this first exercise have taken roughly the same path, and each has done something extra that would get them an approving smile from their teacher! Let's start with the simplest, Tiggum's tight and functional code! code:To be fair, old guessing game programs of this type like to do that too, when they remember to display ranges... The big ol' meanies.   Tiggum's Starship Take-Off in action. RickVoid, meanwhile, edited his code as the time limit went by, asking questions and looking up commands he needed. He also used Tiggum's method, but decided to add a “Try Again” prompt. Alas, in the first draft, the “TRY AGAIN” went by too fast before the screen cleared. The problem was specifically in the bolded section... The CLS happening almost immediately after the PRINT statement... pre:1 Z=RND(-RND(TIME)) 2 LET G=INT(RND(1)*20) 3 LET W=INT(RND(1)*40) 4 LET R=G*W 5 LET H=800 6 LET L = 0 7 FOR C=1 TO 10 10 CLS 20 PRINT "STARSHIP TAKE-OFF" 30 PRINT "PLANETARY GRAVITY= ";G 40 PRINT "TO ACHIEVE ESCAPE VELOCITY, THRUST MUST BE WITHIN" ;L; "-" ;H 50 INPUT "SET THRUST" ;T 60 IF T>R THEN LET H=T 70 IF T<R THEN LET L=T 80 IF T=R THEN GOTO 140 90 IF C<>10 THEN PRINT "TRY AGAIN." 100 NEXT C 110 PRINT "INSUFFICIENT THRUST!" 120 PRINT "THE ALIENS WATCH AS YOU FALL BACK TO THE PLANET!" 130 STOP 140 PRINT "ESCAPE VELOCITY ACHIEVED. GOOD FLYING!"  I deliberately lost here to show you the spiced up text Teacher helpfully pointed out to how to make a wait timer with a FOR loop: JamieTheD posted:Checking code, and both Tiggum and RickVoid have got pretty good answers, with Tiggum using Screen MODE a lil' bit early to give the game that good, chunky feel, earning a silver star. As Tiggum notes, however, the "Try again" will ne'er be seen, because the loop clears too quickly... But Rick wanted more player input, and so looked up INKEY$ (Input Key.) Other members of the class decided to chip in, and eventually, this code resulted. code: The dreaded Syntax Error. It gets everyone, sooner or later... Alas... This code needed a little more research. But the original code still works just fine with the exception of the Try Again, and that's fine! RickVoid decided to spice up what seemed a bit of a deadpan narration of danger with his own text. Overall, a good effort! Finally, FredMSloniker, although not overly familiar with BBC BASIC (Having a C64 outside the class), still gamely chipped in with code that ditches FOR loops altogether, instead using a lot of GOTO line codes and counters. However, he also made the game more complex, adding a small piece of code to calculate the minimum number of guesses needed, a guess counter, adjustable difficulty, and cases to allow the player who just didn't get that you have minimums and maximums for your guesses to try again until they hit upon a number that worked. Finally, they made Teacher blush a little, as he'd made some comments about not being able to comment your code, forgetting that REMark (which does just that, turning a line into a comment) exists. FredMSloniker posted:What the hell. Since I'm bored, here's a version that satisfies the criteria and makes things a bit more interesting. I haven't actually plugged it into an Acorn emulator, but it should work. Note that the numbers in 20-80 can be adjusted to tweak the game a bit; you might, for instance, change the step values to 0.1. (Be sure that GM is evenly divisible by GS, and WM by WS.) Note also that this assumes that variables do not have to be declared integer or float; in other words, 1 / 3 = 0.333..., not 0. I also borrowed a quality-of-life feature from RickVoid's version, though I didn't pretty up the game as much as he did. The code's also a bit clunky, as I don't want to use features we haven't been introduced to yet.  Fred's code in action And now, it's my turn, as Teacher, to show a third way to handle these loops! First up, let's tidy the code a little, with the help of the colon, which concatenates lines. It's not perfect, as each line has a practical character limit of 248, and IF cases are better handled with ELSE routines... But it helps us group the code into lines that make sense, like so: code:code: ...And finally, Teacher JamieTheD's showing... How does this work, and so simply too? By taking advantage of the fact we can leave a loop at any time. We already guessed this from the fact we'd leave it for winning, but by organising the code properly, and adding two checks, we've left ourselves a lot of room for improvement. The first check is after we print the title: If it's the first turn, it skips checking for a result. Similarly, if it's turn “11”, there's no real need to check for a result, so we skip too. We could technically put those two together in the same line with an ELSE IF like we did the Warm/Cold routine in line 40, but hey, nobody's perfect, eh? Anyways, a third method of doing things by thinking sideways a little. JamieTheD fucked around with this message at 20:11 on Dec 12, 2015 |

|

|

|

Well, that's a big auld post! It's provisional based on threadchat, but I think everybody did alright! An SSD with the progs all in one place will be edited into the post after tomorrow's update.

|

|

|

|

FredMSloniker posted:Shouldn't line 40 say GOTO 80? Whups, you're right... Edited the listing, didn't edit the post! Fixing now.  EDIT: And fixed. Results post on previous page!

|

|

|

|

FredMSloniker posted:Hello? Teach, you still there? Oh, terribly sorry, folks, despite an appearance of strength, winter has been beating me around the throat and eyeballs, and I've not been keeping up with things as well as I could! In the meantime, however, I would like to talk about the thread contributions made and other stuff! Tiggum posted:I made a game, and you can download it here. Contains the disk file and also a text file with the code in it for the sake of convenience in looking at or editing it. This is a cool program... That, on a normal BBC, would require a reset every time you play it, as it makes Modes 0-2 unusable, and creates odd behaviours in the OS. But does that mean it's a bad game? No! In fact, props for writing that, and it'll be going in the OP later today!  FredMSloniker posted:Oooh, is extra credit an option? Because I could totally code up some BASIC games. Hopefully, by the end of the thread, thread goers will have the confidence to tackle even modern game engines, so I do want to encourage folks writing their own progs with what they've learned. As such, any that are done will go into the OP, sort of like the fanart in other threads, only with more math involved. :P (EDIT: I'll also be checking the C64 prog, don't worry!  ) )Anyways, update has been delayed, I do apologise for this, but I will spoil that today's BBC Game Theater will be... Cit-A-Del CIT-a-DEL CiT-a-DeL!

|

|

|

|

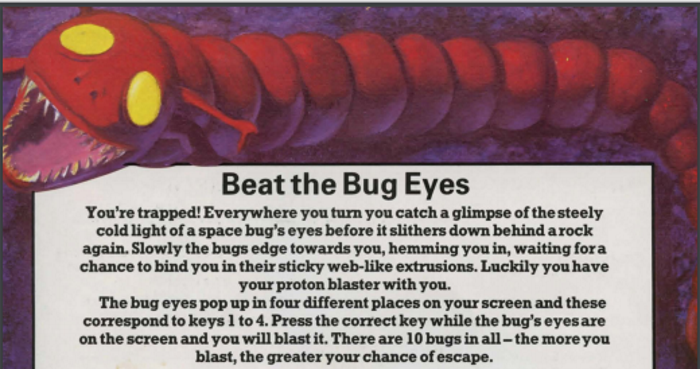

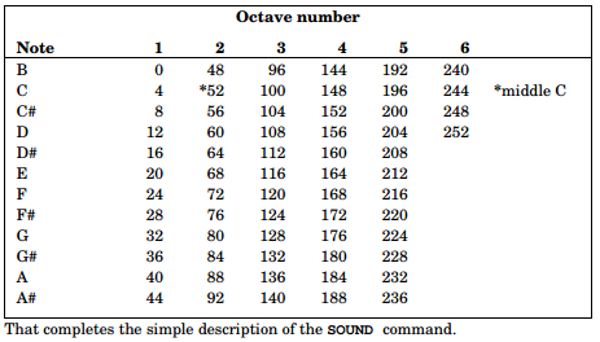

Part 2 – Creating a Shooting Gallery via Text Everyone knows the concept of a shooting gallery game. Well, everyone here, at least. Things pop up, you move the mouse cursor over them, left click, bam. Sometimes it involves a light gun, sometimes a key-prompt... Doesn't matter, all we're doing in a shooting game is glorified whack-a-mole.  But a shooting gallery has things we can play with. Specifically, it has timers. And Computer Space Games and I are going to teach you a kludgy kind of timer that was used way back when... The Loop timer. A loop timer is a very simple thing... It repeats an empty program segment X times, tying up the program's resources in an attempt to stop something that shouldn't happen yet from happening. Nowadays, we can set a program to wait for a certain amount of time while also doing other things (The wonders of multiple calculations per cycle!), but back then, you basically had an empty FOR loop. How does this actually work? pre:BBC CODE

10 PRINT "BUG EYES"

20 LET S=0 Our score counter!

30 FOR T=1 TO 10 Main loop... We have 10 tries

40 CLS

50 FOR I=1 TO INT(RND(1)*30+20) A random timer before we begin, and not a long one

60 NEXT I

70 LET R=INT(RND(1)*4+1)

80 ON R GOSUB 240, 270, 300, 330 Yes, GOSUB/GOTO can have multiple values based on a random number! Surprisingly useful sometimes!

90 PRINT "OO"

100 FOR I=1 TO 150

110 R$=INKEY$(1)

120 IF R$<>"" THEN GOTO 140

130 NEXT I

140 IF VAL("0"+R$)<>R THEN GOTO 210 VAL converts a number string (IE - a number wot is text) into an actual number

150 LET S=S+1

160 CLS

170 GOSUB 350

180 PRINT "*"

190 FOR J=1 TO 300

200 NEXT J

210 NEXT T

220 PRINT "YOU BLASTED ";S;"/10 BUGS"

230 STOP

240 LET D=5 These lines set up the position of the Bug Eyes

250 LET A=1

260 GOTO 350

270 LET D=1

280 LET A=9

290 GOTO 350

300 LET D=5

310 LET A=18

320 GOTO 350

330 LET D=10

340 LET A=7

350 FOR I=1 TO D This entire GOSUB could technically be done with PRINT TAB(A,D) ...

360 PRINT

370 NEXT I

380 PRINT TAB(A);

390 RETURN

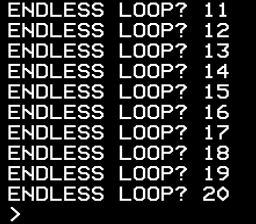

“Aha!” I hear you cry “Surely, that means we can create an infinite loop, and hang the computer?” Hehe, nice try. But the designers of the BBC knew drat well you'd try this, because they were the same kind of jerks you are for thinking it, so two things come into play. First, the FOR loop doesn't change. Once you've set it, you can change the number the loop's referring to, but it won't change the length of the loop. Here, let me demonstrate. code: Ten copies of the phrase “ENDLESS LOOP?”, the numbers 11 to 20, and the prompt. Try again. Secondly, it's stupidly easy to reset a BBC Micro, both in emulated and normal form. It takes all of five seconds, including the second or so of startup. There's also a break condition by pressing the ESC key. So yeah, can't soft-lock with a FOR loop. You can technically do it with the other kind of loop a BBC has (REPEAT...UNTIL), or a GOTO loop (10 GOTO 20, 20 GOTO 10) but again, it's stupidly easy to get out of. Another thing to keep in mind is that a FOR loop runs as fast as the computer can access it. This means that the timing on a BBC B's FOR loop is not the same as on a BBC Master 128+ (Which was, in nearly every way, just plain better), or a C64 (Which also handles the timing differently), or, in extreme cases, QuickBASIC for DOS (Which can be run on modern systems, and... Look, it's recommended you use DOSBox if you're going to QBASIC it up...  ) )In any case, once it's done its waiting (100 loops, as a general rule, is 1 second on a BBC B), it'll put two Os (OO, for Bug Eyes. Oh-ho-ho) in one of four set positions. It takes a teeny bit of trial and error (Or knowing the code) to guess which one, because they don't number them. How does it do this? Well, again, it's trying to lead us in with baby steps, and it's doing it the kludgy way, with more FOR loops. First, it sets up a GOSUB, with 3 lines in each subroutine (LET A[cross] = Thing, LET D[own] = Another Thing). Within the GOSUB, it has a GOTO, so we don't accidentally set Across and Down as up to four different things in order (The last LET for a variable is the one the computer remembers), and it sets up...  One of the terrifying Bug Eyes. 1 to 4 is clockwise from the left, in case you hadn't figured it out ...Another FOR loop. Can you guess what the theme of this one is? This particular FOR loop hits PRINT a number of times equal to D[own], basically like the program hitting ENTER repeatedly until it's at the right place, and then it TABs (Like the TAB key on your keyboard) A[cross] times. Then it comes back, and prints the Bug Eyes in that spot. Cue... Yet another FOR loop. This one, however, is actively watching for you to press a key, with the INKEY$ command. Unlike INPUT$, which will happily stop the program until you hit ENTER, INKEY$ is only waiting for a single key, and it's not going to wait around for you. This is why it checks it, 150 times, for a total of about one and a half seconds. If you pressed a key, it'll come out (with another GOTO), and check whether you got it right. Got it right? It'll replace the OO with a *, add a point to your score, wait for 4 seconds, then start from “I cleared the screen.” Otherwise, it'll just go back to the screen clearing. It'll do this a total of 10 times, then tell you how you did.  The changes box, for those of us playing along on non BBCs. Symbols in the OP. Now, this is a good time to point out something amusing. That first line in the code? Useless. Yes, we know the game is called “BUG EYES”, because we typed the sodding thing in. But once you play it, that text will be up on screen for... 1/100th of a second before the display refreshes. Because gently caress you, that's why. You'll find it in other programs too. Exercise For This Session: I'd set it as a class exercise to put that up on screen for a proper length of time, but I think we've hammered home the point enough. I'm also not going to insult your intelligence by giving you the exercise in the book. Instead, I'm going to ask you to add SOUND. So here's how SOUND works. SOUND has four variables: the Channel, the Amplitude (or volume), the Pitch, and the Duration. The Duration's the easiest to explain, so I'll go there first... It goes from -1 (Until you stop it, you bastards), to 254. 1 for D is 1/20th of a second, so 40 is 2 seconds. Amplitude, similarly, is easy. -15 is the loudest, 0 is silence (Why would you do this?), and 1 to 4... Are sound Envelopes, which we'll explain some other time. Pitch, finally, is technically the most complicated. It goes from 1 to 255, and, in the case of Channel 1 to 3, you can use the full range. Rather than try and explain what is what note, here's a table, from the BBC User Guide.  In the case of Channel, however, there's only 7 values. 0-2 are high to low frequency distorted square noises, 3 is a distorted square noise that matches pitch with channel 1 (Allowing some additive sound), channels 4-6 are high to low “white” noise, and 7 is like 3, but for “white” noise. Keep in mind, only four of these channels can be used at any time (up to 3 distorted squares, and 1 of the noise channels.) There is more, allowing you to play the channels at the same time, but we'll save that for another time. Because of the way SOUND works in BASIC, you can make rising notes with a FOR loop, and the additional STEP modifier (So the loop, instead of counting 1 at a time, counts... STEP number of steps) allows you to gently caress with the pitch. Here's an example from Write Your Own Adventure Programs (appearing later in the LP) code:Another thing that will help is that you can actually have less lines in a program, by putting a “:” between commands, like this... As an example. code:Now, go hog wild. Tell me, with sound, that I'm starting the game, that those nasty bug eyes are dead (or nommed me in passing), and that I got a high score. Be creative, but please don't hurt my ears. 1 week for this one, and I'll show what I think are the best three next update. Shooting Galleries On The Disks UHayesSpaceGams.SSD ASNIPE – Alien Snipers (With the twist of also being a letter shift game!) ASTER – Asteroids (You'll probably want to increase the timer on this one) BUGEYES – That's this one, folks! BBC Game Theater – Citadel (Superior Software, 1985) Video Platform Adventure Games: A genre that survived a surprisingly long time, considering how they were based on the design of games like this one, which is filled with 80s design decisions that would probably get you lynched in the modern day. Resetting your position if you get damaged enough. Only a few enemies (the Dark Monks of the Citadel) can be killed, and doing so not only requires a little of your life per attempt, but a precise shot into their face. A two item carry limit (One for each pocket, obviously), and monsters that follow you, and are slightly faster than you are (Requiring precise pathing to ensure they never really catch up.) Also, your life is your time limit. You'd think a generation would have grown up despising Citadel. But no, we'd seen much nastier games out there, and this one at least gave us the courtesy of a Death By A Thousand Cuts, rather than “Nope, you hosed up once (to three times), start again!” Better, it does actually have an ending, and it is solvable. But this shows some of the important differences in game design philosophy of the early days. You were expected to have the time to play games through in one go. You were expected to play the game multiple times, making a map as you go, to get a feel for what goes where. You were expected to backtrack through dangerous areas to do the things you need to do (And there is a lot of backtracking in Citadel.) You were expected to quickly understand patterns, and make some nigh pixel perfect jumps. If you guessed a few of the folks who played in the 8-Bit era have a sort of Stockholm Syndrome with game difficulty, and end up gaming masochists (HI!), you'd be correct. But why? The answer, generally, comes in three possible parts. Up until now, Arcade Games had dominated: That's right... Games designed to eat your money were the norm, so most budding game designers' inspirations and comrades at the time followed the coin-guzzler design philosophy. It took a little while for game developers to realise that maaaaybe this wasn't such a great idea for games you bought once, and then never paid more for.  Bedroom Coding: Last time, we took a look at Repton. Fun fact: Tim Tyler was fifteen when he made that game, and then made Repton 2 three months later. This was a time of indie developers and small teams, and not all of them communicated, or were even aware of one another until a game was released. So, unlike today, game design tips were mostly handed out through the many, many magazines that cropped up in this period, and not all of these hints were clever ones. Testing? It Works, Doesn't It? There... Wasn't really a major attempt to seek a metric for difficulty balancing, for the most part, or at least, none that was heard of. So long as the game worked, and people bought it, it was all good. The fact that these games were mostly moderately cheap (£3.99 on average in 80s money, which would have been roughly the price of an indie game today, between £6 and £10.) As such, little things like Dead Man Walking scenarios were... Not always caught. As you might have noticed.

|

|

|

|

FredMSloniker posted:Jamie, you still there? I admit, I haven't done anything for this assignment because Sound is Hard, but I'm hoping the thread hasn't died... Oh, goodness me, no, the thread is definitely not dead (Although I do feel like death warmed over right now... Life ain't too friendly.) Just a quick christmas break, while I struggle with some recordings and a thing for later in the thread.

|

|

|

|

Okay, now there's problems. Gonna have to rewrite and re-record an update, as my external HD code 10'd on me, and I could never really afford a second one to back it up to. So I've lost a lot of poo poo at a bad time. But I'll try and get an update through this week.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 25, 2024 08:40 |

|

Paul.Power posted:I know it's been a while, but this is interesting: Usborne have released PDF versions of all their old programming books for free. Yeah, apologies about that, Winter has been murder, in more ways than one. Lost the LP docs when the external HD Code 10'd (4 Terabytes... 4 sodding Terabytes!), and I am definitively in the ranks of the "Unemployed/Creative Sector" now. It's slightly amusing they did this, because, well, both the Internet Archive and the Museum of Computer and Gaming History kind of beat them to the punch. Nice to see pretty fair copyright terms, though, and once the next update is out, I shall definitely be tweeting about it to them. Oh, and there's no class exercise for the next update, because... Well, you'll see why. Suffice to say, it's DVALLEY on the Space Games disc, and I want everybody to note why this program is different from most of the others we've dealt with so far. Also, I want you to try holding one of the direction buttons, seeing what happens, and seeing if you guess why it happens before the next update. It's neither a good or a bad reason, but there is a reason.

|

|

|