|

as one of the original LF doom posters, it's good to see that LF 2.0 has caught up with the times let's talk about an aspect of climate change that a lot of folks keep forgetting: the widespread inundation of micro/nano-plastics in the biosphere not only is plastic rain becoming increasingly normal, but there's evidence that plants absorb nanoplastics through the roots, which block proper absorption of water, hinder growth, and harm seedling development. relevant articles below: Arstechnica - Plastic rain is the new acid rain posted:Hoof it through the national parks of the western United States—Joshua Tree, the Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon—and breathe deep the pristine air. These are unspoiled lands, collectively a great American conservation story. Yet an invisible menace is actually blowing through the air and falling via raindrops: Microplastic particles, tiny chunks (by definition, less than 5 millimeters long) of fragmented plastic bottles and microfibers that fray from clothes, all pollutants that get caught up in Earth’s atmospheric systems and deposited in the wilderness. Abstract - Differentially charged nanoplastics demonstrate distinct accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana posted:Although the fates of microplastics (0.1–5 mm in size) and nanoplastics (<100 nm) in marine environments are being increasingly well studied1,2, little is known about the behaviour of nanoplastics in terrestrial environments3,4,5,6, especially agricultural soils7.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 20, 2024 05:26 |

|

petit choux posted:So how does everybody feel now about us having till the end of the century or another 50 years before things get bad? limits to growth business as usual model wants a word

|

|

|

|

IAMKOREA posted:Yeah that's what I thought thanks guys, still gonna do the carbon farming thing once I quit... the conversation never changes, does it

|

|

|

|

very proud of you all descending into media-fueled doomposting

|

|

|

|

Rime posted:Limits To Growth once again being proven correct, despite the wailing and gnashing of natalist / human supremacist teeth. uh, no, that's incorrect - have you heard of technological innovation and human ingenuity???? checkmate doomers

|

|

|

|

Wakko posted:urban planning would be a big deal for the left im sure if it held any power anywhere sitchensis said it best: urban planning is where socialists go to die

|

|

|

|

JeremoudCorbynejad posted:can't believe i spent 15 minutes on this but i've done it now, what do you want me to do, not post it? Fantastic!

|

|

|

|

I don't know why so many of you find this thread depressing. Don't be upset that the future is being ruined. Just be happy that you were there for the ride. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o8XZ3r3okZ4

|

|

|

|

Ultimately, it's all pointless. Just enjoy the story.

|

|

|

|

Accretionist posted:Climate Change: The Greatest Show On Earth

|

|

|

|

You really don't have to spend so much useless energy on the future. Climate change is a Faustian bargain. It's what we're willing to do, as a collective species, to keep our lives as they are right now. Industrial global civilization depends on fossil fuel energy and will consume whatever remains in nature, land or ocean. We're living in our own pollutants. Welcome to the Holocene Extinction - either a species either adapts, or it doesn't. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mlUSI5-Jhk Koirhor posted:also cycling 40 miles a week dang Hubbert has issued a correction as of 03:45 on Oct 22, 2020 |

|

|

|

Wakko posted:isn't a faustian bargain where you take a big short term win in exchange for a terrible loss long term? It's a little bit more than that. Goethe missed the point. John Michael Greer posted:What makes Marlowe’s retelling of the story one of Elizabethan England’s great dramas, though, is his insight into the psychology of Faustus’ damnation. Faustus spends nearly the entire play a heartbeat away from escaping the devil’s pact that ultimately drags him to his doom. All he has to do is renounce the pact and all the powers and pleasures it brings him, and salvation is his — but this is exactly what he cannot do. He becomes so focused on his sorcerer’s powers, so used to getting what he wants by ordering Mephistopheles around, that the possibility of getting anything any other way slips out of his grasp. Even at the very end, as the devils drag him away, the last words that burst from his lips are a cry for Mephistopheles to save him.

|

|

|

|

Wakko posted:oh i see, thanks. then its definitely not that because we made sure of human extinction at least 20 years ago. History shows us that we still took up the bargain, eventually saw it for what it really was, and kept going anyways. We're getting dragged down anyways.

|

|

|

|

Perhaps I was doing too much sincerity-posting earlier, but I'm gonna keep going. I was probably the biggest LF doomer regarding ecological and energy catastrophe. I've spent over a decade being crack-pinged over resource depletion, climate change, global pollution, crashing biodiversity, and the limits to growth. In the greater history of the planet, this is just the Sixth Extinction Event. It isn't an overnight disaster - once kick-started, it can take thousands of years. Take the Permian–Triassic extinction event, for instance: New insight into the Great Dying - https://phys.org/news/2020-06-insight-great-dying.html posted:A new study shows for the first time that the collapse of terrestrial ecosystems during Earth's most deadly mass extinction event was directly responsible for disrupting ocean chemistry. Driver of the largest mass extinction in the history of the Earth identified - https://phys.org/news/2020-10-driver-largest-mass-extinction-history.html posted:As a next step, the team fed their data from the boron and additional carbon isotope-based investigations into a computer-based geochemical model that simulated the Earth's processes at that time. Results showed that warming and ocean acidification associated with the immense volcanic CO2 injection to the atmosphere was already fatal and led to the extinction of marine calcifying organisms right at the onset of the extinction. However, the CO2 release also brought further consequences; with increased global temperatures caused by the greenhouse effect, chemical weathering on land also increased. What we're living through right now, as industrial civilization, is only a temporary flicker in the planet's history. We will rise, fall, and leave whatever is left for the planet's inheritors. This is one of Dr. Hubbert's key messages.

|

|

|

|

Cup Runneth Over posted:Sort of tempting to embrace boomer selfishness now. "Sure, the planet is hosed in 100 years, but there's no way I'd live that long anyway. Just don't have kids and enjoy civilization's twilight years, then punch my card and check out before things get really dire!" Craig Dilworth, Too Smart for Our Own Good: The Ecological Predicament of Humankind, page 393 posted:The fundamental problem as regards the continuing existence of the human species is that, while we are ‘smarter’ than other species in our ability to develop technology, we, like them, follow the reaction, pioneering and overshoot principles when it comes to dealing with situations of sudden, continuous or great surplus. In keeping with this, and also like other animals, we are not built so as to care about coming generations, other than those with which we have direct contact. As Georgescu-Roegen says, the (rat) race of economic development that is the hallmark of modern civilisation leaves no doubt about humans’ lack of foresight. Hubbert has issued a correction as of 23:49 on Oct 22, 2020 |

|

|

|

Cup Runneth Over posted:The thing is, giving up my present luxuries isn't even an option. I'd be happy to prioritize coming generations over my own, but it's not happening. There's absolutely nothing I can do, so why care? You do you, I guess.

|

|

|

|

Hairy Marionette posted:Speaking of mindfulness helping us deal with the horrors we have wrought. I found “The Happiness Trap” to be immensely helpful. It’s about Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which is more broadly about learning to live a meaningful life amidst all the horror. It makes heavy use of mindfulness. There's a good few chapters on mindfulness and its importance for coping in The Last Hours of Ancient Sunlight.  The point of my advice is not about coming to terms with anything, or succumbing to despair. It is about doing what you can for who you can, for the betterment and happiness of those around you. Ultimately, life might not matter in the end, but at least you did something that mattered for someone. edit: sorry for hijacking the thread

|

|

|

|

Hodgepodge posted:you underestimate how slowly civilizations die

|

|

|

|

Banana Man posted:I still vaguely remember a guy that predicted the end of civilization by 2025? guy mcpherson

|

|

|

|

Koirhor posted:I see that some of you are still in the bargaining phase

|

|

|

|

The age of limits are here.Article Abstract posted:Achieving ambitious reductions in greenhouse gases (GHG) is particularly challenging for transportation due to the technical limitations of replacing oil-based fuels. We apply the integrated assessment model MEDEAS-World to study four global transportation decarbonization strategies for 2050. The results show that a massive replacement of oil-fueled individual vehicles to electric ones alone cannot deliver GHG reductions consistent with climate stabilization and could result in the scarcity of some key minerals, such as lithium and magnesium. In addition, energy-economy feedbacks within an economic growth system create a rebound effect that counters the benefits of substitution. The only strategy that can achieve the objectives globally follows the Degrowth paradigm, combining a quick and radical shift to lighter electric vehicles and non-motorized modes with a drastic reduction in total transportation demand. spime wrangler where are you get in here Hubbert has issued a correction as of 06:49 on Nov 5, 2020 |

|

|

|

Lostconfused posted:I am not reading all of that but, lol peak oil really did happen? Hahahaha. quote:Adapting to the depletion of oil (and especially that of high quality) is a key motivation to decarbonize transportation, although not so publicly recognized. The estimations of the decline in global peak oil dates and rates vary among authors in the literature [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. Most global oil extraction forecasts predict stagnation in 2020s decade. Although there are some uncertainties related to the amount of non-conventional oil that can be exploited, there is much consensus on the decline in conventional oil, while the historical data from 2006 onwards show that the production of conventional oil is already stagnated [[18], [19], [20], [21]].

|

|

|

|

cardiacarrest123 posted:So I went and had a son before I really was introduced to the full horror of what’s coming. He’s only 5 now and It breaks my heart thinking about what I brought him into. I know that most likely everything is futile at this point, but all I do anyway is research what might be the best skills and knowledge to have in the future . I can teach him some layperson medical skills and gardening but my question to you guys is: What does the little dude enjoy doing?

|

|

|

|

take_it_slow posted:Jorgen Randers, one of the original authors of Limits to Growth, from his 2012 book 2052, making concrete predictions about that time period based, in part, on the original LTG models. Hey there, I just wanted to thank you for this book recommendation. It's a great read.

|

|

|

|

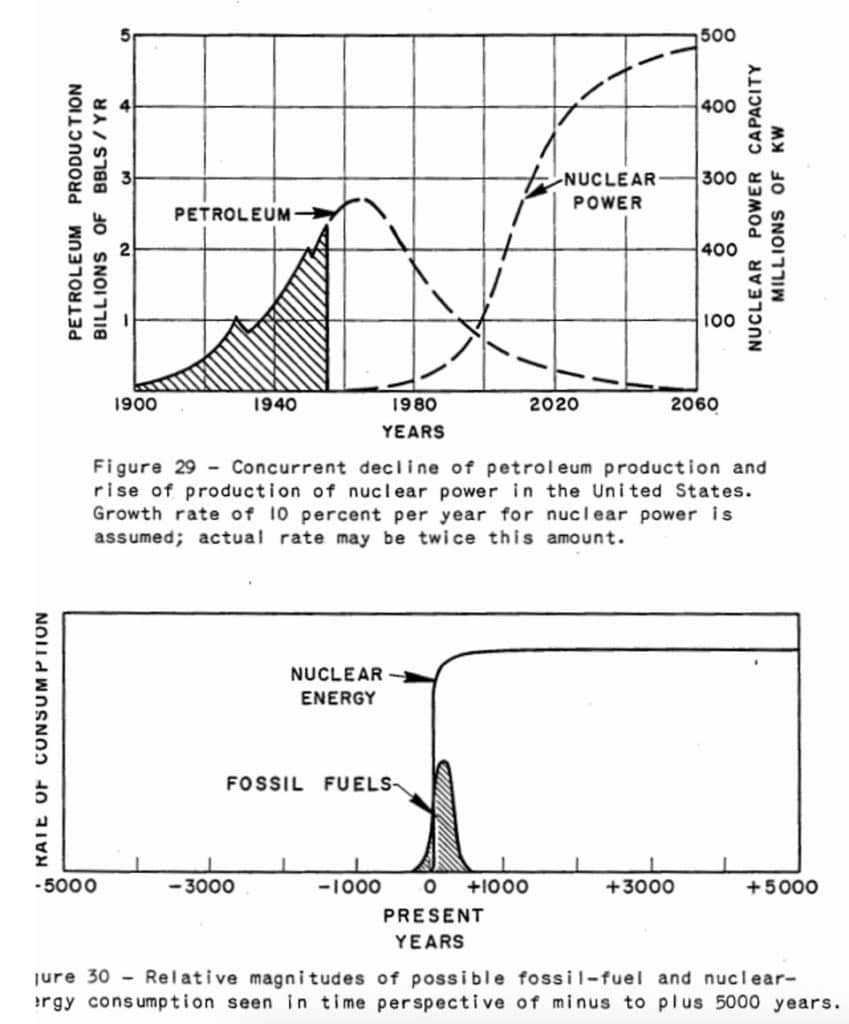

Spime Wrangler posted:Going to spend a lot of time thinking about this graph and lollin as we approach the intersection, assuming the trend holds. i wonder if anyone predicted anything for 2030 ...  -- that said, i will always probably disagree with nuclear energy  and before anyone tries to be clever and say that dr. hubbert supported nuclear energy in the 1950s, he eventually started to espouse solar in the 1970s instead due to the cost ... and the risk associated with nuclear waste in ruining the planet. industrial civilization in its current form cannot survive without fossil fuels, and our chance for mass nuclear breeder reactors was over 60 years ago. the downshift is only beginning

|

|

|

|

As it becomes clear that the limits of growth (which includes the "pollution" of climate change) are a reality, the rich and powerful will grab as much as they can, and not worry much about the poor and the weak. Think about the degree of change you’ve seen in the last 100 years: social, technical, cultural, political, environmental. All of these changes, they are less than what you will see in the next twenty, maybe thirty years. There will not be the ushering in of a golden age for humanity. We are moving into a conflict-filled time, where people are going to do terrible things to each other.

|

|

|

|

Banana Man posted:i hope someone eats my rear end

|

|

|

|

Taintrunner posted:oh good lord we’re seriously doing the zac Snyder is a master satirist actually meltdown again, and somehow in the loving climate change thread would you say that the thread's climate is changing?

|

|

|

|

have you guys considered that everything will be just fine?

|

|

|

|

I remember a time when I dreamed that breeder reactors would fuel the future.

|

|

|

|

glad to see that c-spam is finally sufficiently doom brained

|

|

|

|

well, climate change and resource depletion are great examples of "discounting the future"

|

|

|

|

i remember being the lone crazy doing mega climate change / resource depletion effort posts in LF back in 2008-9 i'm glad that you've all finally descended to my level

|

|

|

|

Shipon posted:Greta redemption arc incoming I think everyone who spends a little too much time studying and advocating for all of this stuff has a phase where they end up flirting with anarcho-primitivism / neo-luddism / deep green philosophy.

|

|

|

|

Koirhor posted:2050 is the new 2100 THE FUTURE WE CHOOSE: Surviving the Climate Crisis - Excerpt posted:It is 2050. Beyond the emissions reductions registered in 2015, no further efforts were made to control emissions. We are heading for a world that will be more than 3 degrees warmer by 2100.

|

|

|

|

WorldsStongestNerd posted:With a tape measure. Perry Mason Jar posted:Five figures but they say it's six figures.

|

|

|

|

Accretionist posted:It's such a steady procession of things going wrong. Craig Dilworth - Too Smart for Our Own Good: The Ecological Predicament of Humankind, page 393 posted:The fundamental problem as regards the continuing existence of the human species is that, while we are ‘smarter’ than other species in our ability to develop technology, we, like them, follow the reaction, pioneering and overshoot principles when it comes to dealing with situations of sudden, continuous or great surplus.

|

|

|

|

MightyBigMinus posted:the megafauna were the first to fall to the capitalist ape This is also covered in the book I quoted earlier.

|

|

|

|

Real hurthling! posted:the IEA is declaring we are at peak oil...demand me, plugging my ears with bitumen: "PEAK OIL ISN'T REAL PEAK OIL ISN'T REAL PEAK OIL ISN'T REAL" -- ""The Atlantic - The World Isn’t Ready for Peak Oil" posted:Two months ago, the world experienced a historic collapse in oil prices, as coronavirus-related shutdowns cratered global demand, briefly turning prices for May delivery negative. Prices have since rebounded modestly, but they remain unsustainably low for countries that depend on oil exports to generate government revenue. Hubbert has issued a correction as of 04:16 on Mar 20, 2021 |

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 20, 2024 05:26 |

|

CODChimera posted:how is this not setting off every single alarm bell and red flag that we have?? because most of this is discussed through national defense agencies who are well aware of the problem (at least a decade or two ago) gwynne dyer's climate wars is a great book

|

|

|