|

mellonbread posted:Vampires are generally assholes, so if you make lots of historical guys vampires you either have to say that the historical character was secretly evil, or just pick a guy who's already considered to be bad. Rasputin basically got claimed by both vampires and mages

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 27, 2024 07:27 |

Robindaybird posted:Rasputin basically got claimed by both vampires and mages Though I think the big badass Puppeteer was a thinly disguised Jim Henson

|

|

|

|

|

I think it's also a long-running joke that Rasputin was a vampire werewolf wizard demon ghost fairy. Now I'm imagining White Wolf devs in 1994 having interoffice rivalries over who gets to claim which war criminal for their product line.

|

|

|

|

Halloween Jack posted:It's a long-running cliche how World of Darkness games insisted that history was made by humans, but quickly went back on that by making historical people into vampires and wizards, and revealing that human history was all shaped by stuff that vampires and wizards did thousands of years ago. In Revised the vampires pulling strings was walked back somewhat - although of course Ericsson wanted vampires running everything back - though it took Requiem and Rose Bailey's "vampires don't run the show, they just buy the popcorn" approach in Requiem to get where it should have been. Nessus posted:Though I think the big badass Puppeteer was a thinly disguised Jim Henson Another famous Jim, Morrison, was a Cultist of Ecstasy!

|

|

|

|

I think different splats claiming the same historical figures could be taken as an amusing “unreliable narrator” thing that slyly undermines the idea of supernaturals being the real actors of history. That probably wasn’t the intent, though.

|

|

|

Silver2195 posted:I think different splats claiming the same historical figures could be taken as an amusing “unreliable narrator” thing that slyly undermines the idea of supernaturals being the real actors of history. That probably wasn’t the intent, though.

|

|

|

|

|

I know werewolves, vampires, and mages have all claimed Jesus at one point or another. Thank you TB:CoG.

|

|

|

|

Can Jesus Frenzy, the greatest thread in the history of GW.net, locked after 11,523 pages

|

|

|

|

|

If Jesus is a wraith, he didn't ascend to Heaven to sit at the right hand of the Father, and presumably will not come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. Wrap it up Trinitailures

|

|

|

|

Kurieg posted:I know werewolves, vampires, and mages have all claimed Jesus at one point or another. Thank you TB:CoG. Silent Striders' take was more preferable. "Dunno what he was but Wyrm creatures wouldn't come within a mile of him." Which they would use to ambush Wyrm critters who moved because of the displacement.

|

|

|

Halloween Jack posted:If Jesus is a wraith, he didn't ascend to Heaven to sit at the right hand of the Father, and presumably will not come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. Wrap it up Trinitailures What are Jesus’s Dark Passions (WJDP)

|

|

|

|

|

Nessus posted:What if his wraith was his human half while his God half returned? If he was fully Man, he would have had both psyche and shadow Flipping tables at moneychangers?

|

|

|

|

If it turns out that the three aspects of the Trinity are actually the Ba, the Ka, and the Khaibit, I'm still going to say the Trinitarians got owned.

|

|

|

Kurieg posted:Flipping tables at moneychangers?

|

|

|

|

|

Look at that bitch just sitting there eating wasps like she owns the place

|

|

|

|

Nessus posted:Getting mad at fig trees? Yelling at his dad in a garden because THIS IS BULLSHIT DAD! WHY DON'T YOU COME DOWN HERE AND GET CRUCIFIED IF IT SOUNDS LIKE SUCH A GOOD IDEA!

|

|

|

|

:ackshully: Jesus is canonically a Lasombra

|

|

|

|

Kurt Cobain pops up as a ferryman in (I think) Ends of Empire.

|

|

|

|

Is he scatterbrained?

|

|

|

|

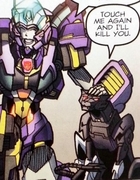

Loomer posted:Previously on...  A Morbid Initiation, Part 5: Part 2, Chapters Ten to Twelve And we’re back! We’re now skipped even further ahead to April 1888, and we have Part Two’s little header: ‘In which a night society is revealed, and a young woman ensnared within it.’ Welp, that about says it all. Chapter Ten Boulle establishes dates more clearly this time around, with the Blake family arriving for the Season on the day before Good Friday. Lord Blake has been missing quite a bit of parliament, but he’s also in deep mourning so no one’s gonna say poo poo about it. And he’s serious about it:  This is a nice touch. It’s above and beyond for his dear wife, and Boulle is correct that men could often get by with just wearing an armband, though a new widower might be expected to ensure a black suit even in the country depending on station. Coburg fabric, though, I’m not entirely sure is appropriate – its okay if its just the lining, but if it’s a facing it’s a very odd choice indeed. And since broadcloth is standard for the outer layers, we’ll assume that’s the case. Regina is also dressed appropriately:  Three months in, crape and bombazine are correct, though Regina is actually fine to wear tasteful jewellery by now, especially cameos or the infamous hair-jewellery. (Also, bombazine is a magnificent word just in general.) The effect of this, of course, is that Regina is about to enter vampiric society while dressed in peak goth-dream couture, complete with all that elaborate lace in the form of crape. Naturally, she’s still rather tormented by the events of Lion’s Green. What’s she been up to since? Has she been crusading? Has she immersed herself in folkloric studies? Studying some early, anachronistic form of suffrajitsu in anticipation of the next time she plunges into an evil lair? No. She has merely sat about, waiting, avoiding her father. There is some justification for this inaction, though, beyond mere grief and shock:  Lord Blake also refuses to hear a word of the supernatural dimensions. Its all just mad slavs, arbitrary murders, and nothing more. Blake, Boulle need not tell us, knows better than that – he simply doesn’t want to know or hear more. He even had Morris, the coachman, whipped. This is, incidentally, a crime – beating your servants went out quite a while before 1888. However, we also know Blake is accustomed to Egypt, and Britain’s colonial rules were always looser so even where it was formally prohibited there tended to be a blind eye towards ‘self-help’ approaches. Is this a mistake, or clever characterization? I’d wager mistake, as we slip from this sequence of parental rage and isolation (complete with two forced hours of kneeling on a stone floor to pray) to another of the Parliament mistakes:  Parliament, again, has been sitting since February. The Easter break that marks the onset of the season is exactly that: a break, for a couple of weeks. Parliament does not sit only during the Easter Term. I’ve mentioned that it’s the little details that suck you in, but the danger of them is also that mistakes like this will throw you right back out. Boulle, unfortunately, sometimes stumbles blindly into them and each time I go ‘dang it, Phil’. In any event, they’ve returned to the London House, which gives a characterization moment:  Mr. Goosehound, ‘Blake’s agent in the city’ – by which we must assume he is a butler or house steward of some variety, not a business agent – has had the house placed in deep mourning. The house itself is located here:  It’s a good part of town. Not the best, but good. Brook’s and The Guards are practically next door. The place is properly shut up against the light, and has had all colour and life removed. We also meet another named servant:  There’s one conspicuous point of white in the black cloth draping everything: a calling card, for Seward’s sister:  Christ, but I hate these fonts they’re using – and I reiterate my earlier point that calling cards do not typically include an address. Regina is immediately off to visit, and we scene cut to Chelsea. Boulle is quite right in his description of the Claremont residence:  The only caveat is that the place is almost certainly a terrace, not a particularly grand house. John and Joanna have a daughter, Millicent, and shipping money. Regina and Joanna were thick as thieves in Egypt and still are, so Regina wastes no time in spilling the beans about the funeral and asking after Seward. There are limits, however:   Without these details, Joanna raises the prospect of body snatching for dissection. This is a bit of a temporal mix-up but it’s a charmingly middle class fear and fits nicely, so hey, gently caress it. Regina rejects it, since it doesn’t fit the elaborate burial ceremonies, and after a brief contemplation of the coroner they arrive to the conclusion that Regina must find the truth, and Joanna, of course, must help her. Seward senior raised his kids right. But where to start? Why, the same place we end this chapter:  Straight to the very heart of the beast, of course. Chapter Eleven Smash cut to Joanna and Regina as Regina boards the Blake’s hansom, driven by the family’s town coachman, Gerald. I’m not actually entirely sure what kind of carriage the Blakes ought to have – if they have their own coachman it implies they aren’t hailing cabs, and I’m not sure hansoms were usually privately owned. If anyone knows, pipe up. Joanna is getting cold feet, and she’s quite right here:  Its unsubtle but I dig it anyway. The more important part is that Regina is immediately going to Park Lane, unescorted, to call on Lady Merrit. This is… Well. Let’s let Joanna explain the matter:  Ah. That’d do it. And Joanna is quite right to wonder, because Park Lane is the street of London – proper old money, old nobility, old connections. That said, it also hosted more than brothel in its time, because, well, that’s just how London was. For Merritt to have her establishment there is nonetheless a sign of real, genuine prestige and power. I also briefly note Joanna is reluctant to spill these beans and has to be cajoled into it – she doesn’t just go ‘oh it’s a whorehouse dear’, but holds out for a solid hour. Nonetheless, confess it she does, and Regina departs to visit a whorehouse on the first night of her return to London. Even the coachman thinks it’s a bad idea, so the place is infamous enough he knows of it… and reveals something significant:  This is not entirely news to us. We already know Emma and the Ducheskis had some kind of connexion to Merritt – as does Regina. Nonetheless, she raises no eyebrow, but does interrogate Gerald to know why he’s so hesitant:  Ah. It really is the belly of the beast – Elysium. This makes Regina’s snap decision to attend, and be left there with her coachman returning home without her despite warnings of express danger, even more reckless. But as reckless youth will, she’s set on her course, and Gerald takes her to Merritt’s Elysium. On arriving, we’re told Merritt House is a rare fully detached affair in a very dense part of London, set back from the street a ways – ‘as if the compacting effect of the crowded capital had left this home untouched.’ Regina interprets it as a sign of power, and she’s certainly not wrong, though not quite the power she thinks. However, we then hit a point of immense frustration to me.  Footman. The term is footman. A houseman is an American thing, and does not answer doors. A valet attends a gentleman personally, and may answer a door when he is the only servant or only manservant, but not in a larger establishment. Here, it is either a footman or a porter. This not the more niche pedantry I also do – this is basic stuff. And speaking of basics, ‘do not publicly announce your attendance at a brothel’ ought to be basic too, and yet…  Oh, Regina. Silly girl. As an aside, the lackey here opening the door is slightly unorthodox. Regina’s own servant ought to do that, but in this context it can be excused. Now admitted, Regina follows the man in through a rose garden, and predictably, manages to scratch herself on a thorn. She’s bare-armed, no gloves, which is acceptable for an afternoon visit to a friend but not quite appropriate for an evening affair. At this point, she’s admitted to the real deal – past the roses lies Merritt’s pleasure gardens:  We’ll be spending a lot of time here in this trilogy. For Regina, any hope of discretion is lost when the footman announces her, but all she can feel is excitement. It’s an excitement tinged by orientalism, with a faint hint of the sexual:  Fascinations with the harem and the women’s quarters are a constant of the genre, but again, this is uncritical repetition. Handled more deftly, it could tie neatly to Regina’s emerging sapphic desires, as she once again enters a hidden world of beautiful women, but Boulle doesn’t really follow up to either interrogate or exploit, so it’s a bit of a wasted thread. Lady Merritt’s description continues on – her dress is a crimson sheen, woven into a ‘delicate crepe’, which is a frustrating description to me as crape per se is a mourning fabric, while crepe as a whole can be any number of things with very different appearances. Fortunately for Regina, she welcomes her without too much fuss, as Victoria ‘has great taste’. Oh dear. At this point Boulle introduces us to two more significant characters:  They are, respectively, one Theo Bell and his sire, Don Cerro. Both have period art:   Theo’s portrait is, as it goes, my favourite from all the depictions of him. It’s the nose, I think. The two introduced by name after a brief interlude:   This is not quite so clear cut as the text might suggest – not for any specific reason involving either, but because we already know that in Boulle’s conception of Victorian vampire, reflexive projection of lusts via Presence is a thing. Also, I again repeat my earlier point about hourglasses: this is 1888. Corsets are in. Wasp waists are very much in. Steel boning and eyelets to support tightlacing are in. There is no norm outside of heavy physical working women of masking the shapes of the waist, and even for those women, it’s not a fashion norm so much as mere brutal pragmatism. The part that is unusual here is the wasp waist itself, which can only be achieved through a combination of tightlacing and strategic padding and layering, but its unusual not for daring to show curves but for the extremes of those curves. It’s like saying ‘wow, ten inch high heels! High heels are so unusual!’ – you’re missing the drat point! Fortunately, my ire is swiftly deflated by the scene moving to Regina being introduced to Don Cerro and Bell. Don Cerro is a handsome fella but I do have to laugh at this:  There’s a reason I’m not calling Regina a lesbian. But I’m also at the stereotypes on display. They work fine, they’re a bit of fun. Moving on, Regina is wising up. She immediately realizes something is queer:  Unfortunately for her, Don Cerro touches her cuts and dissolves her awareness. This prose makes me laugh:  It’s not good! We’re going for the frisson, the moment of shuddering delight, that tremble up the spine that blurs pleasure to pain, that makes something that ought to be shunned be so perfectly desired that its unbearable. Instead, we get ‘a slight burn’ courtesy of ‘callused and electric’ fingers. Bell’s introduction is its own kettle of fish. He is, as we already know, a mountain of a man. What is his first defining characteristic beyond his stature and skin? Wellll…  Ah. An enslaved person. In and of itself this is not necessarily objectionable, and Don Cerro is very much being an rear end in a top hat, but we’ve already seen Boulle dipping into exoticization and fetishization, so it isn’t great here. To his credit, though, he does more with Bell later. Bell leaves Cerro and Regina alone so Cerro can feed, seducing Regina off into the gardens, which are implausibly large in a way that’s actually perfect for the theme and the vibe.  This is uninspired. As an attempt at the erotic seduction, the whole things fall flat, and the prose is serviceable but a bit clumsy. In Boulle’s case, I’m prepared to credit that it’s probably deliberate, to show the artificiality of the enforced passion. But before it can go too far…  Victoria to the rescue! Cerro is actually feeding, of course, and Victoria is displeased. Only she gets to eat Regina. Things escalate quickly, with Cerro lapsing near to frenzy over Victoria’s interference, and we get to why I’m inclined to think the flat passion is deliberate:  Victoria taunts Don Cerro some more, but before we can get some sweet, sweet vampire-on-vampire violence…  Meet Juliet Parr, my single favourite VAV NPC. She’s the sheriff, so that bit earlier really was foreshadowing.  Don Cerro gets his anger under control and Boulle confirms the deliberate flatness of the erotic here:  He departs, and Victoria offers her thanks. Parr points out she needs to better watch her pets, with the implicit threat of executing Regina if Victoria fucks it up, but then we scene cut.  Merritt’s garden is too big for Park Lane, but the idea of an entire secret garden hidden in plain sight, observed but uninterfered with, is perfect fantasy. It also tells us just how powerful Merritt or her patrons are without needing to really say it – they can steal a large swathe of the most valuable land in the city without anyone even realizing. Victoria, of course, is pissed at Regina not for putting herself in danger, but for putting her in an awkward position:  Then she flips to comfort, and it’s a good moment. Its false, and cruel, and an artifice to manipulate Regina. She asks why Regina didn’t just come to her house – rightly – and Regina doesn’t quite know:  Regina is a pawn in a very big game none of the others quite realize is unfolding until the end. It’s safe to say certain of her actions are not wholly her own. Victoria nonetheless agrees to be Regina’s guide in the world of the Kindred, which is definitely not at all her weaving a web of control. She emphasizes the need for secrecy, then sends Regina to Joanna’s in her barouche, where she strips nude and passes out in the guest bedroom. Why nude? Unclear. That’s where we end chapter eleven. On the whole, I want to like this chapter, but I don’t. The flat eroticism of the Don Cerro scene is a good idea but the execution lets it down. Merritt’s gardens delight, but the errors drive me up the wall. Regina having agency is good, even if it’s not wholly her own, but the challenges to it are dismissed too easily. Chapter Twelve We pick up the next morning. Seward has called on Joanna and they’re discussing Regina.  Smooth, Joanna. Regina is still asleep and its past midday – blood loss’ll do that.  That’d be Cedric, Victoria’s ghoul. Seward, to his credit, recalls the man’s existence and connexion with Ash, but mixes his name up. That doesn’t go far, though, as Joanna is too busy pumping Seward for the full story of Christmastide, then urging Seward to defy Blake and go upstairs to Regina. He refuses and leaves, and we scene cut to Regina’s return home.  Who doesn’t love a classic brood? Regina tries to explain but he’s not really there. He’s in himself, and downs the rest of his whiskey to summon up the nerve for what comes next.  And the dark secret is revealed. Blake knows. He doesn’t suspect, he doesn’t fear, he knows. And he knew before he married Emma. His initial appearance still tells us what we need to know about the man – what we now see is what terrifies the man at his core, his deep wound that colours everything that follows. Not only is all he wanted slipping from his fingers, but it slips into the clutches of true and unadulterated evil. Naturally, he pleads.  Regina promises. As before, she is conscious it’s a lie. We scene cut again, this time to something new. Here’s a little thematic music.  At last, we see the Taurus Club. Pall Mall is indeed the heart of prestige Clubland, so the Taurus Club is a proper one by its very presence there. Seward’s been before as a guest:  This is the beating heart of advancement for men of merit in the Queen’s armed services. Sir Christopher Bartow, a general, is there – a bastard son with no money or name, who’s risen to his rank by virtue of the Taurus Club. This being a Vampire novel, well, you can probably guess what’s really going on. They discuss the tedious business of peacetime soldiering for a little while. Seward is in full Club fancy:  These clubs, for those not in the know, are essentially the secret bureaucracy binding Empire together. The definitive work on the subject is Club Government by Seth Thevoz, who writes that: quote:Clubs served as a semi-public, semi-private space; one which carefully controlled the admission of members and guests, and which tightly controlled what information was disseminated to the public… Bernard Capp has identified ‘the twin spatial significance of the law – both institutional and “occasional”’, and it is precisely this boundary that clubs straddled. There’s some basic question and answer. Who proposes him? Pool. Has he a token? Yes – the bull’s head talisman we saw that night in the carriage house, where Regina spat it aside in a not-so-subtly-symbolic act. And then it gets odd.  Smash cut back to Monroe House and Regina, in case we missed the symbolism of sacrifices. She’s sneaking out unseen, only for Gerald the coachman to notice her. She asks nicely and he agrees not to tell anyone because… reasons? She slips off and hails a hansom to visit Victoria in Bloomsbury, specifically at her residence at 49 Charlotte Place, a tall 3-story house. This, as it goes, checks out, save that there is no 49. If, however, we relocate Victoria to the nearby Charlotte Street, the house exists, was of 3-stories, and we can even get a glimpse at a street view:  This also avoids the prospect of Victoria living in a house built in 1860, when the Charlotte Place development was constructed over former mews. Cedric is there to pay the driver and lead Regina inside, all without a word.  Charming. Also… Correct, on the placement of the ‘salon’. We can chalk that up to an affectation of Victoria, but drawing rooms on the first floor of a townhouse could either face the street or the back yard, so – full marks, Mr. Boulle. We’re then given more confirmation of Victoria’s regency tastes, in case anyone thought I was being too harsh on the subject of her gown:  The conversation begins with Victoria querying Regina’s health, then its on to ‘this is a dangerous game, be careful’ boilerplate. The only noteworthy element is that Regina is not inclined to simply take it:  Her attempts at bravado, however, are easily quieted, if not entirely silenced:  I think that’s meant to be wary, not weary. In any case, Victoria drops the Dread Stare and emphasizes that there are many dangers in this new world Regina enters. When Regina asks to know more, she extracts an oath.  Ah, the old classic Blood in the Port trick – but no! Here’s Victoria with a dose of honesty:  Okay, not entirely honest. But she does lance both Regina and herself, though Boulle misses the trick of upselling the erotic dimensions of the act – the mingling of their blood in one cup, the act of penetration, etc. She’s got two glasses out, one sans port for herself (because hey, vampires can’t eat food!) and they drink.  Cue a brief erotic phantasm focused on Victoria’s tongue and the thought of it on her neck, and then we end the chapter thus:  Another hit-and-miss chapter. I’m a sucker for a good sinister club, but I do wish the Victoria scene had more weight to it. Regina isn’t hitting the right balance for me in how readily she’s folded, which would ironically enough be better met by emphasizing the erotic. Dumb youth getting in over her head for a true frisson of desire that she tries to tell herself is only in pursuit of the truth is a strong motive to go along with things like ‘drink our blood’, while here her infatuation isn’t quite developed enough to give it that quality and it feels a little bit too like fiat. Up next: A return to the Red Death.

|

|

|

|

At least we didn't get something like "Is it true that Black vitae is... different?" with Bell.

|

|

|

|

joylessdivision posted:Yelling at his dad in a garden because THIS IS BULLSHIT DAD! WHY DON'T YOU COME DOWN HERE AND GET CRUCIFIED IF IT SOUNDS LIKE SUCH A GOOD IDEA! Vampire Jesus, who gave his blood for you and now wants it back.

|

|

|

|

Midjack posted:Vampire Jesus, who gave his blood for you and now wants it back.

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:Previously on The Masquerade of the Red Death - Book 2: Unholy Allies - Part Two, Chapters 18 to 20: We’re back again with good ol’ Bob Weinberg. I’d hoped someone might post a review of something to break up the Loomer Readathon but c’est la vie, I guess. Last time we got a telepathic ghoul flipping around a luxury penthouse in her underpants exploding heads. Are we getting around anything that gonzo this time? Nope! Let's read on with...  The Masquerade of the Red Death - Book 2: Unholy Allies - Part Two, Chapters 21 to 24 Chapter 21 We’re still with Alicia for now. It’s been two hours and the remaining two Sabbat ghouls in the neighbourhood have been mirked off-screen, and she’s even had cleaners come and handle the matter, presumably paying them with a single gold coin while dressed as Keanu Reeves. The building has a ‘resident skyscraper physician’ who’s come up to look at Jackson, who needs a week’s rest. As an aside, are those… a thing, in the states? It’s a good investment to have for sure but Bob doesn’t really address it as part of Varney’s infrastructure. He does address the rest, though. Jackson and Varney get to work transferring control of Varney’s business empire to branch offices so they can shut down the skyscraper completely. This should be a logistical nightmare, but  Still sounds like a nightmare, but hey, why not. I reckon working for them during covid lockdowns would’ve been a dream if they can roll out work from home easily in the mid 90s. The reason she wants the building vacated isn’t just to spare human life, though – she’s making the building a trap for the real assault force ‘Galbraith’ is going to send after her. Bob takes the chance for some exposition and to explain, in case we couldn’t work it out, how Alicia survived the fiery inferno at the Naval Yards. One fun element of this – they taped it, and Bob lets us know how long Madeleine Giovanni was on film saving McCann, for ‘a few frames’. Assuming the cameras were standard VHS – Bob just calls it videotape – and a few is three, that puts her there for roughly 1/7th of a second. Call it a thirty meter sprint in and out before the blast goes and she’s cruising at a good ~750KM/h. Is this a scientific approach? Lmfao no it is not, but it makes me grin like an idiot the same way talking about Victorian textiles does. At this point, Jackson narrates his capture – he got caught sleeping, so that’s embarrassing. We find out where the cross came from:  Style points for coming up in two limos, one of which is just hauling lumber for something that feels vaguely racialled charged. But there’s an important detail: they nabbed Jackson in the day, before ‘Galbraith’ returned. And that means…  And that, in turn, unlocks an immediate ‘well duh’, since Bob built this mystery with all the finesse of Gallagher:  In fairness, it’s also a ‘big surprise, right?’ moment in the text. Bob’s got a lot of flaws but he’s self-aware enough to know he’s not exactly pulling off a Rex Stout on this one. The chapter ends on a promising note. There’s a prophecy Alicia needs to look into – lame. To do it, she needs help. Who from?  Hell yeah! Phantomas en route! Chapter 22 Unfortunately, we don’t hop to Paris. We have to hop off to the outskirts of DC first, and Madeleine’s truck of lovable scamps. It’s a rainy night, and Sam needs a piss courtesy of the noise. There’s a crucial flaw in the truck’s turn as a hotel:  The solution? Walk to an abandoned service center and use the john! Sam vetoes because it’s a crazy idea, so the solution turns into ‘go under the truck’. A solid page of toilet logistics, and then we’re straight into gunfire. It’s the mafia. They want to know where Madeleine is, and they’ve shot Pablo. To Junior’s credit, he’s not a rat:  Convincing? No! Who’s going to leave the truck unlocked with the keys in the ignition?  Oh. I guess it is. What’s in Junior’s head? A lot, actually. Bob lets us in there with slightly more than his usual skill.  Bob tries for pathos, but he never quite lands. I appreciate the effort, though, and Junior has the tragics down. A little more about Sam and hoping he can keep them distracted would be a nice touch too. Unfortunately it then takes a turn for the gratuitous as they ask Junior if he’s ever hosed a woman, so Lazzari’s going to eat him soon. As an aside, in more competent hands I’d think it deliberate that Lazzari asks if Sam’s ‘known’ a woman while Tony the Tuna asks if he’s ever been screwed, but not so much in Bob – the potential ambiguity in there is accidental. White Wolf’s publications, especially the early ones, had very little queerness in them despite… everything, really, about their Ips, though given examples like Angel in Dark Prince that might be for the best. We end the chapter with Lazzari ordering his goons to blow up the truck and driving off with Junior in… ‘three huge black touring limos’. Does anyone drive a regular car except Walter? Chapter 23 It’s a hop and a skip over the pond to Paris, where we are at last reunited with… Le Clair and Baptiste, the two surviving members of the Unholy Trio of Stooges. They’re still in Phantomas’s tunnels, but any dramatic tension in their exploration has been bled off by a… 7 chapter and 70-page diversion to the East Coast and loving Vienna. It looks like the dearly departed Jean Paul was the brains of the outfit:  This, of course, segues immediately into Le Clair realizing that yes, there are in fact secret doors. Baptiste, though, is an idiot, and Le Clair has to explain to him what sliding walls mean for an entire page and a half. Baptiste’s characterization is all over the shop – he veers from ‘dumb, but dangerous’ to ‘legitimately quite handicapped’ as Bob needs. Le Clair uses his magical power to sense Phantomas to triangulate, and Baptiste is set the task of literally smashing the walls down with his fists, and then, since he sees no reason to stoop, decides to make a bigger hole:  No notes, except one:  Phantomas is there to greet them, down the tunnel. He’s the ugliest vampire Le Clair has ever seen, because Bob don’t go for things by halves, drat it. Unfortunately for them, they can’t just race to get him:  You can fit a drat space shuttle in there if you clip off the wings and fin. Wood might’ve been a slightly better idea than metal for the spikes, though. I unironically love how all the traps in Bob’s stuff are hugely over the top and ridiculous. This one’s more than just a giant hole, for instance, because sometimes you gotta go for the classics:  Phantomas is just straight up building Indiana Jones-grade death traps under the middle of goddamn Paris and it rules. Alicia Varney has an acid trap a thousand feet below New York, because why not? If this was in Boulle’s work I’d be going ‘what the gently caress’, but the charm of Bob is these moments of gleeful idiocy. How will they get out of it? Clever disciplines of the kind we already know can disable mechanical tricks? Baptiste smashing the slab until it stops moving? No. We get a call back to book one:  The plan works, and there’s no tension. They try nothing else – there is no failure. Le Clair lands safely, and Baptiste, though he nearly misses his landing, is simply so strong he can dig into solid rock and haul himself up meter by meter. The one point there is is that Le Clair wants to use this chance to murder Baptiste. You may have spotted the flaw already. He’ll have to fight Phantomas alone if he does that, and his plan to kill Baptiste boils down to… ‘knock him off the cliff and into the pit’. Baptiste. The impossibly strong, tough ox. I’d put money on him surviving the fall myself, and metal stakes won’t even put him in torpor. The actual betrayal is visceral enough:  Baptiste loses his grip and flies, blinded and betrayed, into the very pit. Will we see him again, in a rare case of Bob leaving a dangling thread that can return later in the form of an enraged and betrayed goliath, who – tying in with last chapter’s themes – discovers a sense of kinship to Phantomas when he is given consolation and blood while imprisoned in the pit?  Hahahaha no of course not. Of course there are flamethrowers. We end the chapter with Le Clair’s inner monologue:  Bob is so close to actually saying and doing something with his characters around a shared thesis statement here and last chapter, but he pulls back each time. It’s deeply frustrating. Chapter 24 Keeping with our pattern, we’re off to Vienna again, where Etrius is being the dumbest oval office alive. In today’s example: Etrius does not understand delegating.  Etrius has, you may recall, already delegated crucial responsibilities to Peter Spizzo in investigating the Comte St. Germain. He can manage that, but not delegating… paying the goddamn light bill. Insert something here I guess about how men will literally become thousand-year-old immortal blood sorcerers rather than going to therapy. Speaking of Spizzo, he’s turned up for a meeting unannounced when Etrius is expecting Elaine de Calinot. Is it just me, or does something seem off:   Oh, I’m sure it’s nothing. He’s been jetting around the globe exploiting the House of Secrets:   Conceptually? Neat! I might even steal it for my Mage game as an unstable ancient treasure stolen by the Tremere from the Order of Hermes when they split. However, it disappears from the canon after this novel, at least as far as I recall. I suspect the part where it lets the Tremere cross the globe in an instant, without needing to… do anything… may have played a part. Etrius gets a report on Germain, and again feels something slip in behind his eyes to watch. He’s sure its Tremere, which seems like a big leap now he’s becoming more aware of being manipulated from day one, but sure. Spizzo reports he spoke to elders who’d met Germain, but no one can remember his features.  Subtle, Bob.    Gasp! Could it be that the Red Death really is the Comte St. Germain? Well, obviously, yes. But he’s not just a regular noddist:  Oh, Bob. Stop trying to make Lameth a thing! Having read some of his other work, he loves weird invaluable artifacts as plot devices. The Devil’s Auction is all about them, for instance. Etrius is sure the Apocrypha has not resurfaced, if it ever existed. We end the chapter with Bob ruining his own writing. He could’ve cut right here:  It’d be clunky, but the implication is clear – even just on ‘Are you sure?’ would work nicely. Instead, Bob spells it out:  He’s often so close to a good line, then goes a little too far, or doesn’t push just that extra sentence in to get there. But that’s Bob. Next time: The end of Part 2, featuring: vampire deathsquads, Phantomas, and Part 3’s Return of Makish.

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:

A Morbid Initiation, Part 6: Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen  Well, we’re back again. I’ve been holding off to keep from turning the thread into the Loomer Readathon but since its again been a couple of weeks I thought we might as well crack on. We left off with Regina Blake being bound to Victoria Ash as she pursues the shocking truth of her mother’s mysterious (un)death. Chapter 13 …and we pick up right where we left off. Victoria, offscreen, explains the rudiments of the Masquerade without mentioning that the secret society is vampires, then we get some further details on the page. The importance of secrecy, the strange familial quality, the semi-egalitarianism of having commoners, etc, etc. Regina has one first question: What do they want?   I really like this as a description of the Camarilla. There’s no ‘we run the world!’ so much as a tacit acknowledgement that they are parasites on the world, who happen to work to keep it stable – though unfortunately, and rather oddly for a Victorian period piece, Boulle doesn’t really explore just what this looks like. This, of course, is extreme poverty for the majority of the population, parasitic wealth extraction, and a general disregard for the rights of anyone not part of the in-group: the perfect conditions for predation on the majority of humanity. Boulle dips here and there into a little sliver of the poor, but his focus remains almost exclusively on the well-to-do and important, without any of the mixture of erotic disgust at and tragic lament for the working class that epitomizes so much Victorian literature. We’re perspective hopping this chapter, and cut to Lord Blake, who continues to crumble in the face of evil:  Boulle takes a moment to inform us Blake would have remained in the cold peace of Durham, and this is a nice little touch of the modern seeping in – the crumbling old manor house is a place of safety, and the city of untold horror, rather than the other way around. Then we’re back to why, and to Blake continuing to crumble. He’s been having bad dreams since he came to London, drowning them in whiskey. And fair do: They’re pretty creepy!  Tonight he has another dream, only it doesn’t follow the form. Emma’s there, and surprise: its not a dream, she’s there to say goodbye and kiss him one last time (and throw in a feed for good measure) though he’s so drunk he’ll think it was. This one mingles with flashes of dead soldiers on his Egyptian campaigns, and I again find myself frustrated in that Boulle could’ve done more with the tensions and corruptions of colonialism in a motif with vampirism, rather than using it as an excuse for a kind of ‘foreign devils corrupting our women and, by extension, the very heart of Brittannia herself!’ arc. Emma is a sloppy eater:  This is also the end of the chapter. I’m of two minds about this specific paragraph at the end. It’s a good spot to cut to something else, and in terms of Emma being sloppy and not knowing to cover her tracks, this is actually effective foreshadowing. Emma isn’t intended to live long. To the Tremere, she is disposable and a pawn for a specific ritual, not a real person. But I also actively dislike it because the entire chapter is short and a bit muddled, and this ending sequence is a good example. Its perfunctory and robbed of punch as a result. Chapter 14 There’s a time jump between 13 and 14 as the book enters Summer and the height of the Season. This is right in terms of timing, but does give me pause. The London sequence began ‘the day before Good Friday’, which in 1888 is March 29th – thus, they arrive on the 28th of March. The entire sequence from chapter Ten to Thirteen spans a fairly short period in April, and Chapter 14 takes us to the middle of June. We’re effectively skipping the entirety of May, and though we’re given some fill-in details on what happens in the interim, it feels like there’s a desire to mark time away that doesn’t necessarily fit with the narrative’s pacing. But, my qualms aside, Boulle informs us that in the interim, Regina has been drawn deeper and deeper into the night world as her father continues to wither in the face of evil, drinking away the hours, though now he spends the nights at one of his Clubs. This also gives me a moment of ‘hm’ – Blake fears and abhors the London nightlife, but the Clubs lie at the very heart of it, so its an unexpected shift and one that jars. And what of Regina’s nightlife? Well, let’s let Boulle explain.   Pure licentiousness, I guess. There’s a strong element here of dependence cultivation, of replacing one collapsing affection with another in a search for stability, which works almost well enough to distract me from Boulle’s continued blunder about garments. The shape of those bodices requires extensive structuring so even with that lower neckline (appropriate for evening wear, though Victoria’s regency-cuts are still dated) Regina is not free from shapewear, nor would she have been skipping a corset in her mourning attire – and while it might have been interesting to place Victoria among the devotees of the natural form and rational dress movements that’s not to be found in the text. But there is one aspect of this I do like, and it’s the prospect Regina is being deliberately dressed slightly absurdly as a way of marking her as part of the in-group. Unfortunately, I don’t think that’s the intent. The weeks have included multiple visits to Lady Merritt:  I’m not entirely sure the detail about inheritance helps matters, but that’s a stylistic decision. These visits provide a chance for Regina to begin noticing the signs and symbols of herds, ghouls, and affiliations:  This, I love. There are other parties as well.  This party is our focal point for the chapter, so we’ll let Boulle set the stage.  Pretty swanky stuff. The lights are right, too – the British Museum was the first public building in London to have electric lighting for more than just a demonstration, and rolled it out through the 1880s. The bigger display of playing by their own rules is the candles, though: they’re banned in public spaces there and for good reason. I have a pedantic quibble about the valets – Boulle means footmen – but that’s neither here nor there. What’s with the tokens?  It ain’t Bertie. The calling card signifies he won’t be attending, and one clue of the tensions is that this is Dr. Edward Bainbridge’s party, which Boulle slips in then moves on immediately to Regina noticing Don Cerro and Theo Bell, using that as the way to introduce Bainbridge:  Its not subtle, but its an effective way of informing us of the full tension between Don Cerro and Theo Bell, and what Theo’s seeming emancipation actually means in the context of unlife, which becomes more important later. Bainbridge finds it all a little distasteful.  But what, as Regina asks, is Don Cerro’s role? Bainbridge isn’t terribly circumspect and explains the concept of an archon to Regina so that we readers can be reminded of what one is. Basically: Vampire FBI. They chatter on for a little while, Bainbridge obliquely explaining the tradition of Elysium being sacrosanct, and then we return to the plot itself when Regina notices his ring:  Gasp! I don’t actually like the size of the sigil here – its much too ‘LOOK AT ME!’ for what it needs to be. Part of why this falls flat is that though Regina immediately recognizes the sigil from her horror at the Ducheski burial… we never saw the sigil there ourselves, just had it described to us. It surfacing this way has no repetition horror, no ‘oh god’, as a result. Vampire fans know it, sure, but in that case we don’t need it shown here and not previously, so even there it’s a misstep. In any event, Bainbridge is as subtle as the scaling:  Regina, smartly, falls back on her social programming to continue making polite smalltalk as though she has no idea Bainbridge is linked to her mother’s mysterious death… for all of five seconds. Her resolve to do is on the same page as her bluntly asking about the ring:  Subtle! Bainbridge explains it away as a fraternal symbol drawing from old sacred geometric texts, which is not exactly a lie. I do enjoy his reply before we cut away to Lord Blake:  The number of reputable gentlemen getting involved in weird Masonries and occult fraternities is huge in the late Victorian, so it’s a perfect reply in every way, right down to the smug ‘I know something you don’t’ vibe. Blake’s off for a walk, meanwhile, though its afternoon so we’re also cutting through time. Where? Oh, the infamous Highgate Cemetery of course! Its precisely a month from the raising of the maypole, which we’ll assume means May Day in this context, though that creates a timing error, and the Whitsunday alternative is no better. He’s come to visit his dead friend Henry Lewis, who died fighting a vampire with him in what is now revealed to be 1869. What exactly happened that night? Boulle takes the chance to tell us.  We leave Blake sitting there, ruminating on his failure. This is the rest of Blake’s arc in a nutshell: how does he claw his way back from his failure to rip out the evil root and stem that now consumes his family? Our cut is back to an old friend, Eleanor Ducheski, and Anton Wellig. Anton’s pissed that Emma has been roaming about doing poo poo like messily feeding on her widower, which, frankly, fair. Wellig has set up a hidden chantry in Hampstead, where Emma’s a prisoner whose conditions are about to significantly tighten:  Why call Gareth? Why, to sic him on Regina, of course, because another Ducheski servant to Bainbridge has reported her presence at the Museum ball. This is another misstep, as it removes any shock value when Gareth resurfaces despite last being seen burning alive. Its also where we cut again to three days after the Ball, this time to Regina and Victoria, night-boating on the Serpentine in Hyde Park. Regina, sensibly enough, wants to know how Bainbridge is connected to the Ducheskis, as she’s interpreted the symbol as a Ducheski one. Its all very atmospheric, very gothic:  It could do without the last sentence, honestly. Victoria teases Regina by replying he’s probably not a relative, so she has to puzzle out the connections in laborious detail, then takes a stab that earns a reward of information.  Victoria’s rather amused at Regina asking if she’s a Tremere, and the conversation turns to the inevitable: how did Victoria meet Emma, if the Tremere own the Ducheskis? To get there, Victoria orders up some more inductive reasoning from Regina about the social standing of Bainbridge and the Tremere, which in short form, is ‘fragile’. Since she gets it right…  Boulle laces passages like this through their shared scenes, with varying effectiveness. The whole is largely satisfactory but a little clumsy at times at selling us on a deepening blood bond mingled with a pre-existing desire. Victoria then finally explains that she met Emma when the Tremere were not in ill-regard with His Majesty the Prince.  This is marvelously creepy and prompts Regina to recognize that Victoria is astonishingly well preserved for being at least forty, and that this is perhaps a concern:  Boulle makes a relatively rare indulgence in world is a gently caress when we land with a coachman driving to a place for reasons he cannot recall, to pick up someone he cannot recall. We know nothing of the gentleman save this:  Do we need to know this? Not particularly, and it feels like Boulle remembered ‘oh yeah world of darkness’ and threw it in. Whoever’s cooking his memory has been doing it since 1885, sometimes for days at a time – and he’s not alone:  The client is Juliet Parr, the Sherriff. Boulle provides a rather nice description of obfuscation in action.  I like this. It’s a little clunky but conceptually its very cool – the idea that its some deep-rooted shiver in the belly that says ‘turn right and keep walking, you didn’t see poo poo’ is appealing. Parr’s on the hunt.  Also a nice touch – we don’t often see Sheriffs doing… Sheriff stuff, really, in VtM material. Killing, sure. loving with protagonists, sure. Having to go quiet a leak politely but firmly? Not so much. You may recognize the number, though: It’s the home of Joanna Seward, which is deeply unfortunate for her. I’ve mentioned I love Juliet Parr as a character, and I’ll pull hard from Boulle here since I still like this prose.  Juliet is a monster in the guise of a pleasant, slightly obsessive young woman, and her obsessiveness translates into terrifying efficiency at what she does. In this respect she belongs to the tradition of the not-quite-neurotypical detective, only she uses her skills to, well, torture people who are speaking out of school with precisely considered tools and methods. Her actual madness is perfect for a Victorian piece – hidden by a perceived madness of transgressive gender beliefs, she’s obsessed with secrets, with knowing, with putting things just so, and it lets her embody the principle that Kindred law is, at its core, a matter of the gunman’s command enforced through horrific violence and nothing more. This is also where we end the chapter and this part – with Juliet on the threshold of an atrocity left unseen. Next time: Telegrams to Cairo! Gratuitous sex-murders! The Taurus Club!

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:A Morbid Initiation, Part 6: Chapters Thirteen and Fourteen Thank you for keeping up with these!

|

|

|

|

PoontifexMacksimus posted:Thank you for keeping up with these! It's my pleasure. I'm mostly just holding off on posting more often because I don't want to completely spam the thread out. But, since I've already got this reply open... A Morbid Initiation, Interlude 1: A Monstrous Interlude No book chapters today – instead, I thought it might be worth piggybacking on the ending of last post to explore something fundamental to the World of Darkness: Monsters. The monster is something beyond and deviant from the norm, which we use to question and ultimately reinscribe that norm. To borrow from Cohen, ‘Every monster is… a double narrative… one that describes how the monster came to be and… its testimony, detailing what cultural use the monster serves’, and this is pretty much the text of Vampire: the Masquerade distilled down. Each Clan is its own set of monstrous stereotypes that explores the cultural use – the margins of acceptable behaviour – that they demarcate. Last time I posted about really liking Juliet Parr as a monster, and a big part of why is how precisely her character matches the monstrous in multiple dimensions. The most interesting one is the third of Cohen’s seven monstrous theses – the category crisis. In Parr’s case, she’s a walking one. She crossdresses and acts in a masculine role while retaining a fundamentally feminine identity (which, in addition to offering some juicy drama, is a real Moment in the Victorian – the emergence of the Public Woman is coalescing together between the vast landscape of women’s clubs, the huge number of women in employment, and the increasing expectations of suffrage and education), but more importantly, she joins this with her actual Malkavian derangement. Other people have already written extensively on the way Vampire conceives of madness in essentially Gothic (and thus, Victorian) lines, so we won’t dwell on that. Instead, I want to consider Juliet’s specific madness, which is what the Malkavian clan is about questioning and dissecting (albeit usually unsuccessfully). Malkavians are an invitation to consider the limitations and (mis)use of the labels of ‘sane’ and ‘insane’, of ‘rational’ and ‘irrational’, and Parr’s a really good example of it done reasonably right. She’s an obsessive-compulsive. Elements of Boulle’s portrayal of her veer into the stereotypical – the insistence on keeping her hair just-so in the last post, for instance – but he grasps something more significant. The compulsions are not just ‘neat and tidy’: they’re intrusive thoughts that reshape your worldview. Juliet Parr’s push her to meticulous cruelty. This is its own problematic trope of the kind VtM often slips into – the dangerous lunatic – but it pairs it with beautiful, cold rationality. The peak monstrousness of Parr is that she presents an inextricable combination that challenges both categories. Is she mad? Definitionally, yes. Is she rational, calculating, and reasoning? Profoundly so. If we dip in to London by Night (and I might do an actual review of that once I wrap one of the two I’m currently doing), we can take a look at her statblock.  There’s a few things I want to really note from this. The first is that despite a strained clinical affect – more on that momentarily – Parr’s actually quite likeable if we believe her stats. She’s also extremely intelligent and very educated in her specific area. Part of this portrayal edges into autism stereotype territory, with a particular resonance of a kind of ‘crazy pretty monster girl’ cousin to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (murderous vampire nightmare girl?) popular in the early-to-mid 00s that’s its own pseudo-gothic stereotype of contagious madness and the combined disgust-allure of the monstrous. The creepy clinical affect is a big part of this depiction – think Summer Glau as River in Firefly, who swaps from screaming hysterically to ‘morbid and creepifying’ and back as and when required. It’s a standard part of the package that Parr is a partial engagement with, right down to her portrait as a big eyed, pale, brunette naif. (I borrowed Emily Browning’s image from Sleeping Beauty in the role for my ongoing Mage game, since she's very good at presenting the right energy: pale, delicate, in some ambiguous way sending signals as both predator and prey - something they relied on quite a bit in American Gods and Sucker Punch.) What makes her a more interesting figure than the stock stereotype is that she is, inescapably, monstrous rather than a figure that’s meant to inspire a twisted mixed urge of desire and protectiveness. She does not flip back and forth between hysteria and ‘creepifying’ – she possesses rigid self-control (or, rather, the appearance of it). And not only is she a vampire, but through the trilogy her appearances are tied far more closely than others to precise and intimate violence than most of the other vampires. We find out in book two her preferred method of conditioning her victims and informants is not merely Dominate, but Dominate paired with extremely precise cuts very delicate and hidden places:  . It also – and this I don’t consider a spoiler in light of Boulle weaving sex throughout the trilogy – is explicitly sexual for her. Parr’s particular approach unites animal lust with higher reason, madness with rationality. She tortures you because she is sane and has the right to do so, but she has the right to do so because she is the mad enforcer of a monstrous predatory system that exists in the service of an impossible, supernatural irrationality. . It also – and this I don’t consider a spoiler in light of Boulle weaving sex throughout the trilogy – is explicitly sexual for her. Parr’s particular approach unites animal lust with higher reason, madness with rationality. She tortures you because she is sane and has the right to do so, but she has the right to do so because she is the mad enforcer of a monstrous predatory system that exists in the service of an impossible, supernatural irrationality. Parr’s razor equally lays open her victims and the truth of modern concepts of sanity as a Foucauldian power exercise, in that it matters both not at all and enormously that she’s insane when she’s working on you, but not in any way that can change what’s happening except to control how it is perceived and the social power it generates as a result. The gender ambiguity she presents – frankly, Parr’s backstory could go either way on ‘merely a suffragette’ or ‘actually a trans man who still utilizes femininity as a social tool for survival’ – is a big part of this as well. As we’ll see in book two, the object of her desire is distinctly phallic, with all the psychological overtones that offers up for analysis and a rather curious extension of the obvious metaphor of vampiric feeding as a kind of monstrous penetration mixed with a very symbolic castration of reason. Parr creates another category crisis, inseparable from the first, around gender and sexuality (and, as a vampire, she of course presents one between living/dead as well.) This isn’t all that surprising since Boulle is quite expressly playing with sexuality and gender norms, even if he’s somewhat clumsy in the execution and takes a tack less likely to alienate readers by focusing almost exclusively on heterosexual and sapphic desire, but there’s something interesting in it all the same. Parr, though she’s presented to us as a woman, is explicitly a deviant one (and again, the trans lens slips in almost effortlessly here) and her engagement in phallic lust, as we’ll see later, takes place in an explicit context of madness and transgression, where a man of reason is laid low by a being who unsettles the boundaries of madness and reason, of man and woman, and symbolically castrated by her and everything her razor represents. Its wonderfully gothic, but it also does something that a good period piece should do, which is weave with modern fears as well as old motifs. This is something all monsters do, or at least those we may properly call monsters. Cohen’s first thesis is that ‘…the monster is born… as an embodiment of a certain cultural moment – of a time, a feeling, and a place.’ In a good period piece, this has to be both the moment of the text’s setting (as it is understood by the audience), and the text’s contemporary time. And this is where Boulle really succeeds at making Parr a monster. She clicks in the moment of time (simultaneous extreme gender suppression and emergent women’s liberation – and the slip there is deliberate: the repression is fixated on all nonconformity. Intensifying over Victoria’s reign in increasing disgust and scrutiny of deviant men as well as deviant women) and for a modern audience that lives in a world where liberal feminism has produced monsters of its own that prey on women and men alike, where the existence of these monsters is presented as a triumph while the same blood-thirsty machinery ticks on uninterrupted. Parr is at the very forefront of feminism emerging, directly inspired by Wollstonecraft, an associate of Mill and Davies. She is a woman taking, by force of reason (facilitated by madness), a masculine place (that of the police and predator simultaneously) in a way that reminds us of the naked force of law and police brutality, of the hysteria over feminism, and even of the tensions within feminism. Her specific role as sheriff is reminiscent of the joke about female prison guards, but paired with vampirism she becomes the face and bloody hand of an explicitly brutal pro-imperial order of bloodsucking parasitic aristocrats, draping herself in the same old authority but using it to symbolically castrate reason, to invade the domestic arena and inflict unimaginable (sexual) horror on the Good Housewife in the body of Joanna, and to usurp the maleness of that authority for her own liberation. In other words: Parr is a walking incarnation of gender panic, gay panic, crisis masculinity and both literal and figurative castration anxiety, and the insufficiency of rationality all at once. Boulle isn’t quite deft enough to do her justice but he gets close, and she’s one of the most interesting characters in the entire Victorian Vampire setting as a result. Parr is a monster both for her times and for the modern era – a genderfucking incarnation of a brutally rational but fundamentally unsane hierarchy who openly combines the power to discipline as law-dealer with deriving sexual pleasure from doing so, whose idea of reason is literally imprinted on the body through a torture the mind cannot perceive or recall. To close out, Cohen’s seventh and last thesis of the monster is relevant. I’ll quote it in full as it appears in Speaking of Monsters: quote:Monsters are our children. They can be pushed to the farthest margins of geography and discourse, hidden away at the edges of the world and in the forbidden recesses of our mind, but they always return. And when they come back, they bring not just a fuller knowledge of our place in history and the history of knowing our place, but they bear self-knowledge, human knowledge—and a discourse all the more sacred as it arises from the Outside. These monsters ask us how we perceive the world, and how we have misrepresented what we have attempted to place. They ask us to reevaluate our cultural assumptions about race, gender, sexuality, our perception of difference, our tolerance toward its expression. They ask us why we have created them. They ask what it is about the vampire, the werewolf, the fairy, that attracts us, and try to distill it into a means of collective storytelling that lets us experience that self-knowledge, interrogate it, internalize it. The same is true of the novels, as shoddy as they often are – and this is really the difference between the ‘proper game’ and the ‘superheroes with fangs’ type. The latter is not so concerned with the monster at all, though it can be really good fun and have amazing moments (Alicia Varney flipping around a penthouse in her underpants exploding heads telepathically, for instance, is so dumb and gonzo that I’m still using it as my benchmark for Weinberg’s ‘dumb but fun’ element) but with a different set of motifs focused around the limits and uses of power and what it means to be a hero and protagonist. Reading Boulle’s attempts at the former at the same time as Bob’s gleeful embrace of the latter is, I think, discursively interesting in this light, since it invites us to compare what we can dig out of each. When we conclude Bob’s first trilogy I’ll take a proper look at three monsters in it (the Nictuku, the Red Death, and Anis) and see what we can piece out of it, and I’ll do the same for this trilogy with three (Mithras, Victoria Ash, and the Ducheski family as a collective whole.) in the same way.

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:They ask what it is about the vampire, the werewolf, the fairy, that attracts us, and try to distill it into a means of collective storytelling that lets us experience that self-knowledge, interrogate it, internalize it. The same is true of the novels, as shoddy as they often are – and this is really the difference between the ‘proper game’ and the ‘superheroes with fangs’ type. The latter is not so concerned with the monster at all, though it can be really good fun and have amazing moments (Alicia Varney flipping around a penthouse in her underpants exploding heads telepathically, for instance, is so dumb and gonzo that I’m still using it as my benchmark for Weinberg’s ‘dumb but fun’ element) but with a different set of motifs focused around the limits and uses of power and what it means to be a hero and protagonist. Reading Boulle’s attempts at the former at the same time as Bob’s gleeful embrace of the latter is, I think, discursively interesting in this light, since it invites us to compare what we can dig out of each. When we conclude Bob’s first trilogy I’ll take a proper look at three monsters in it (the Nictuku, the Red Death, and Anis) and see what we can piece out of it, and I’ll do the same for this trilogy with three (Mithras, Victoria Ash, and the Ducheski family as a collective whole.) in the same way. Amazing stuff. Looking forward to it!

|

|

|

|

Edit 2: forgot to start with: excellent piece, thank you! I always found instructive the etymology of the word "monster", sharing the same Latin root as "demonstrate" - with the original Roman Latin meaning of "a sign from the gods", to quote Etymonline: a derivative of monere "to remind, bring to (one's) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach," from PIE *moneie- "to make think of, remind," suffixed (causative) form of root *men- (1) "to think." https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=monster The monster itself as inherently an act of communication, a call to remember what perhaps we would like to forget. Edit: is this the book the Cohen theses you mention are from? https://books.google.se/books/about/Speaking_of_Monsters.html?id=YT1mAQAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y PoontifexMacksimus fucked around with this message at 01:13 on Apr 16, 2024 |

|

|

|

PoontifexMacksimus posted:I always found instructive the etymology of the word "monster", sharing the same Latin root as "demonstrate" - with the original Roman Latin meaning of "a sign from the gods", to quote Etymonline: a derivative of monere "to remind, bring to (one's) recollection, tell (of); admonish, advise, warn, instruct, teach," from PIE *moneie- "to make think of, remind," suffixed (causative) form of root *men- (1) "to think." Nice etymogising. Made me think of the Culture assassin/torture drone at the end of Banks' Look to Windward.

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:This is the good poo poo right here.

|

|

|

|

PoontifexMacksimus posted:Edit: is this the book the Cohen theses you mention are from? That's the one, yeah. I picked it up when I was taking a course run by Daniela Carpi, who's great (if very Catholic in her understanding of the soul and the challenges AI presents to it), and its a really solid collection of readings. The Cohen bit is an excerpt from his book Monster Theory, if you want to go straight to the source.

|

|

|

|

Loomer posted:That's the one, yeah. I picked it up when I was taking a course run by Daniela Carpi, who's great (if very Catholic in her understanding of the soul and the challenges AI presents to it), and its a really solid collection of readings. The Cohen bit is an excerpt from his book Monster Theory, if you want to go straight to the source. Ah, it's funny, https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/monster-theory is actually the first source I found but I wasn't sure if it was the original or vice versa, because from I saw of the linked it's also an anthology, and that page only listed Cohen as an editor and not a contributor... Academic anthologies can always be a bit of hassle in that way if you don't have an infinite budget. But this would be the right volume to pick up for his writings specifically?

|

|

|

|

That one's also a selection of readings, where Cohen was editor and only contributed the seven theses. The big difference is that the Speaking of Monsters one makes some cuts for brevity - the original is 23 pages, the one in Speaking is 3, so its pretty substantial and some of the theses make much more sense with the full explication, like 2 - the monster always escapes.

|

|

|

|

Hey there - has Mors finished the 7th Sea 2e reviews, since 1000 Nations is missing on the archive? (I'm reading through the thread but it's long and there's lots of distracting other reviews there). If not, I'd like to do it.

|

|

|

|