|

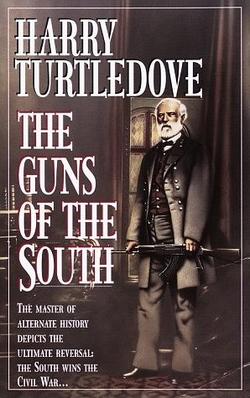

Harry Turtledove is one of the most well-known authors in the genre of alternate history - the past as it could have been. Or, at least, how Turtledove thinks it could, anyway. I'll be going through at least a few of his books, looking both at the world of the books and the history that Turtledove is playing with. In 1588, King Philip II of Spain sent the 130 ships of the Invincible Armada to reconquer England from the Protestant Elizabeth II for Spain and the Catholic Church. That fleet, carrying 18000 Spanish soldiers, was supposed to pick up another 16000 men from the Spanish Netherlands, but aggressive action by Sir Francis Drake, Howard of Effingham and Admiral Sir John Hawkins was able to forestall this. In the decisive Battle of Gravelines, English naval forces sank 5 of the Spanish galleons while losing no ships, and the battered Spanish fleet was further wrecked by wind and wave. By the time the Armada limped back to Spain, a third of the fleet and over 20000 men were gone. The entire affair is regarded as one of the legendary disasters of military history. Or, at least our military history. .jpg) It is 1597. 9 years ago, the Spanish descended on England, smashing aside the armies of Elizabeth and conquering England. Isabella, daughter of Philip II, rules in London, and the English Inquisition hunts diligently for adherents to the banned Church of England - and any secret loyalty to Elizabeth I who sits imprisoned in the Tower of London. We will be following the adventures of a poet, actor, and playwright name of William Shakespeare, and those of a Spanish soldier, playwright, and actor by the name of Lope de Vega. As this book has only two POV characters, a relatively self-contained plot, and no sequels, it seemed like the ideal work to start with. Conventions: Excerpts from the book will be presented as quotes: quote:Like this Plain text will be summaries of unquoted text. Italics will be commentary or background information. Each chapter will be broken into sections as the point of view shifts. This will be labeled in this manner: Chapter 42 - Section 10: McCharacter Any discussion of further parts of the book, or discussion of other books as they relate to this one - character and scene reuse is a common criticism of Turtledove - be in spoilers. In the latter case, I'd prefer that the name of the book (or at least series) you're referring to is mentioned outside of the spoiler. There are some useful terms that will probably come up, so a small glossary is in order. This will be expanded as needed. OTL = Original Time Line (actual history) POD = Point Of Divergence (where actual history changed into book history) POV = Point of View - in this context, it means the character whose head we are currently riding in. This book has two, later series have dozens. (Will probably refine this OP as needed - this is new to me).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| # ¿ Apr 25, 2024 17:26 |

|

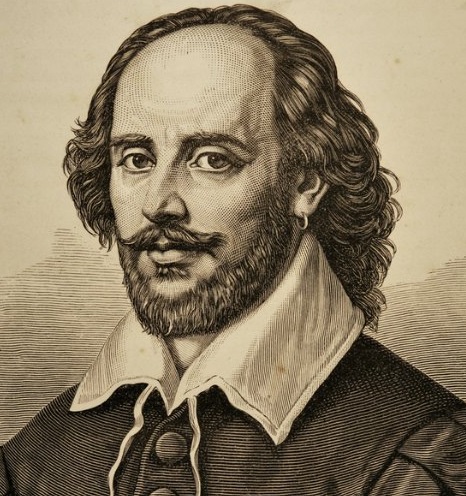

1597 Chapter 1 Part 1: Shakespeare quote:Two Spanish soldiers swaggered up Tower Street toward William Shakespeare. Their boots squelched in the mud. One wore a rusty corselet with his high-crowned morion, the other a similar helmet with a jacket of quilted cotton. Rapiers swung at their hips. The fellow with the corselet carried a pike longer than he was tall; the other shouldered an arquebus. Their lean, swarthy faces wore what looked like permanent sneers. Already, we have a lot to unpack here.  The real William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) was one of the most prominent literary minds in the history of the English language. His surviving works include 39 plays and almost 160 major poetic works, most of which have been translated to every language on Earth. Today, more than 4 centuries after his death, his fame is such that he remains a household name. Born to a country gentleman in the small village of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, Shakespeare left little record of his early life, other than his marriage to Anne Hathaway in 1582, the birth of his elder daughter six months later, and the birth of his son and younger daughter (twins) in 1585. The first recorded performances of works attributed to him occurred in 1592, and he frequently acted upon the stage. The last known acting performances from him date to 1608, shortly before an outbreak of plague forced the theatres of London to close, and his last plays were written in collaboration in 1613. He died suddenly of unknown causes in 1616. Large land purchases suggest that his career made him a wealthy man, and he left the bulk of his estate to his daughter Susanna. Shortly after his death, friends of his compiled his works into the First Folio, asserting that the various other editions of his plays were unauthorized and inaccurate. To this day, there is a conspiracy theory that Shakespeare was a front man for another author, based on the assertion that a country bumpkin like him could never possess the level of genius that was readily apparent in him. We also see mention of the Spanish monarchs currently ruling England – so let’s see what the real ones were like.  Isabella Clara Eugenia (1566 - 1633) was, as suggested in the text, the daughter of Phillip II of Spain and his third wife. Betrothed to her cousin Rudolf Hapsburg (later Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II) at the age of 2, she was ineligible for marriage until Rudolf declared he wasn’t going to marry anybody. Eventually, she married her cousin Albert of Austria in 1599, at which time she was given control over the Spanish Netherlands (this territory being much of modern Belgium and Luxembourg, parts of France, The Netherlands, and Germany, capitaled at Brussels.). Upon the death of Albert in 1621, she joined a religious community (now the Secular Fransican Order) in the spirit of Francis of Assisi. History records their reign as an able one, marked by the virtual elimination of the long-simmering rebellion in the Spanish Netherlands, great patronage of the arts, and significant diplomatic coups. The most prominent diplomatic accomplishments were (ironically) the end of the undeclared war between England and Spain, along with a 12 year truce in the Eighty Years War. Here, the Turtledove timeline and the OTL one doesn’t match up. The Armada sailed in 1588, and this book begins in 1597. As it is stated that Isabella and Albert were crowned immediately on the Spanish conquest, this means that she married Albert a full 11 years early, at a time when she was still solidly betrothed to somebody else. This sort of parallelism is one frequent criticism of Turtledove, and the origin of the thread title. quote:

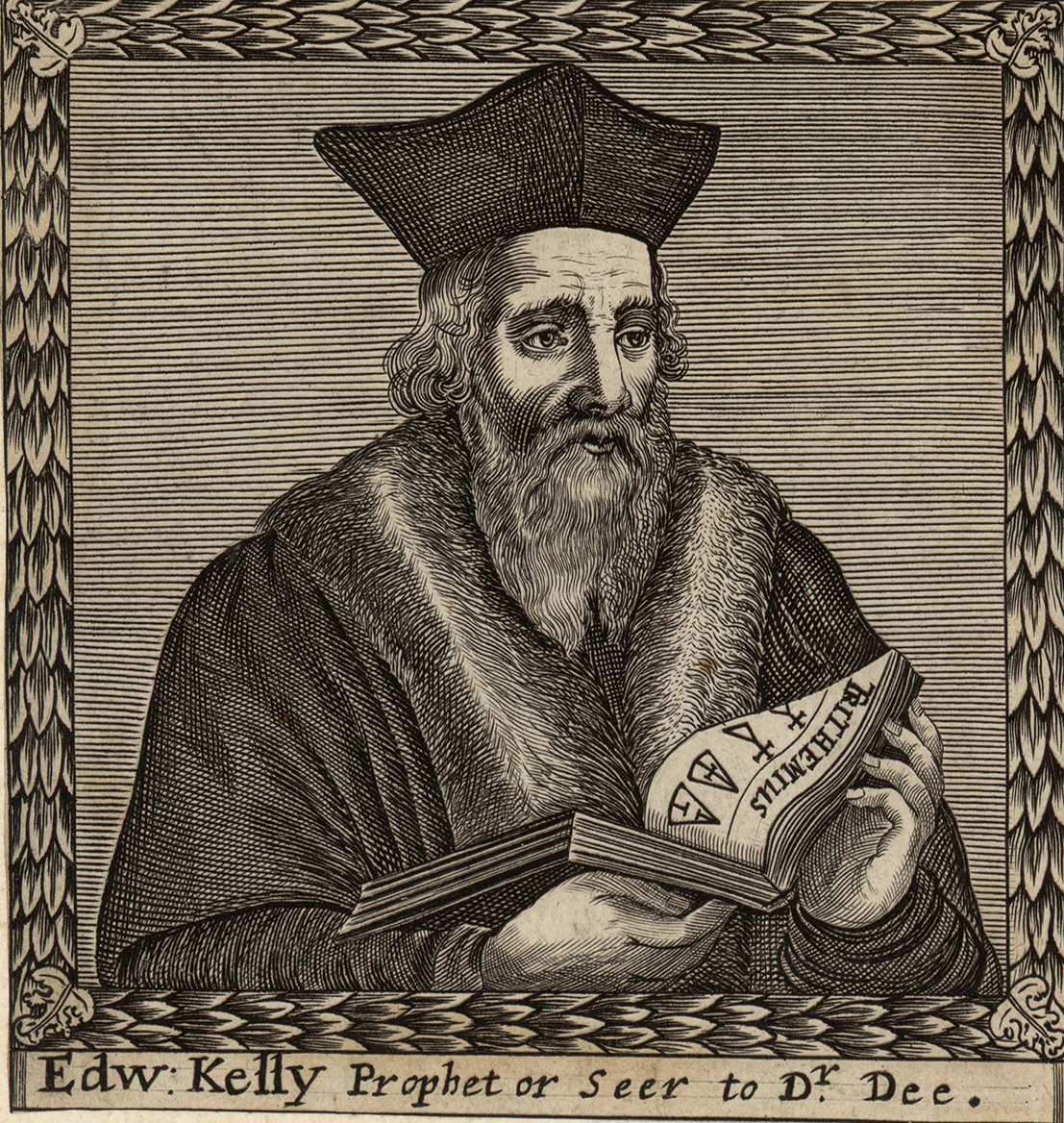

He is distracted first by the arrival of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Parsons and then by the heavily guarded prisoners. First a dozen sentenced to hang, a large number sentenced to condemnation followed by imprisonment or humiliation, and finally a dozen condemned to be burned. Among these latter are a proud and defiant Puritan by the name of Philip Stubbes, and a counterfeiter and alchemist by the name of Edward Kelley. Stubbes is practically rejoicing in his martyrdom, but Kelley is terrified, and desperately tries to convince him that he is repentant in the hopes of at least gaining an easier death by strangulation. His pleas failing to convince the monks, he spots Shakespeare in the crowd and cries out for aid – much to Shakespeare’s dismay as this brings suspicion on him. quote:As it went past, the pikemen who'd been holding back the crowd shouldered their weapons. Some folk went on about their business. More streamed after the procession to Tower Hill, to watch the burnings that would follow. Shakespeare stepped out into the muddy street. Along with the rest of the somber spectacle, he wanted to see Edward Kelley die. Shakespeare does not applaud Stubbes, although others do, due to his fear of the new suspicion placed upon him. He does, however, wonder if he could get away with so brave a character in a play without the audience dismissing him. Some of the prisoners were repentant enough for some mercy and are strangled, but (despite his best efforts) Edward Kelley is not among them. The Queen gives the command, and the prisoners are burned. The real Philip Stubbs was a well-known pamphleteer, most famous for a tract in which he denounced the theater, gambling, drinking, and contemporary fashion. He found no opportunities for martyrdom, and died in 1610.  Edward Kelley was also a real person, albeit one shrouded in legend. He was a partner of Elizabeth I’s advisor and court astrologer John Dee, who claimed to be able to contact angels. Kelley was an occultist and alchemist, famous for his claim to be able to transmute base metals into gold. He also was allegedly able to interpret the language of the angels Dee contacted. The two were accused of necromancy while traveling the Continent in 1587, and were forced to attend a hearing with the Catholic Nuncio of Prague, during which event Kelley managed to issue significant insults to the Catholic Church. In 1589 or 1590, Rudolf II hired Kelley to make gold for the Holy Roman Empire. In 1591 Kelley was arrested by Rudolf II for killing a nobleman in a duel. In 1595 he was released to make gold, followed by his arrest for failing to make any gold. He either died in captivity in 1597 or poisoned himself in 1598. If there is any record of him meeting the historical Shakespeare, I cannot find it. quote:Better him than me, Shakespeare thought as fire swallowed Edward Kelley. The mixture of shame and relief churning inside him made him want to spew. Oh, dear God, better him than me. He turned away from the stakes, from the reek of charred flesh, and hurried back into the city. This is a good setup section. The auto-de-fe is well done, provides an excellent grounding for the setting, and fingering Shakespeare out is a good setup for later. The first sentence is particularly good. The notion of victorious Spanish soldiers marching through London is a very striking image, particularly with the familiar figure of Shakespeare to give it some grounding. Chapter 1 Part 2: De Vega quote:LOPE FÉLIX DE VEGA Carpio had been in London for more than nine years, and in all that time he didn't think he'd been warm outdoors even once. The English boasted of their springtime. It came two months later here than in Madrid, where it would have been reckoned a mild winter. As for summer . . . He rolled his eyes. As best he could tell, there was no such thing as an English summer. quote:"Thine husband?" Despite his horror, de Vega had the sense to keep his voice to a whisper. "Lying minx, thou saidst thou wert a widow!" Lost in the fogs of London, and well after curfew, he proceeds with drawn rapier. As an officer, he need not fear Spanish patrols, but any English out at this time would be criminals looking for somebody to rob. He does encounter just such a man, but they manage to avoid actually meeting, and De Vega eventually happens on a Spanish patrol. They mock him for being out so late and ignoring the rules, chatter about the deficiencies of England and Englishmen, and provide him with an escort to the barracks near St. Swithin’s church. There he finds his servant Diego asleep, which is how one usually finds Diego. He finds the servant all but useless, but a proper Spanish gentleman is never without a servant, so a terrible servant is better than none.  Lope Félix de Vega y Carpio (1562-1635) was a Spanish soldier, playwright, and novelist. The author of more than 500 plays, 3 novels, 4 novellas, and over 3000 works of poetry, he is almost as prominent a figure in Spanish literature as Shakespeare is in the English variety. He is nearly as famous for his amorous affairs as he is his literary one. The collapse of a love affair led to his exile from Castile, followed by his marriage under pressure in 1588. Shortly after marrying, he began his second tour with the navy of Spain and sailed off with the Armada to England. His ship, the San Juan, was one of the survivors of the doomed expedition, and he was not injured. After his wife died after childbirth in 1594, he moved to Madrid and took on several new lovers - one of which bore him several more children – and a second wife. He joined the priesthood after the death of his favorite son and second wife, although he famously continued to take lovers. He died of scarlet fever in 1595 quote:When he woke, it was still dark outside. He felt rested enough, though. In fall and winter, English nights stretched ungodly long, and the hours of July sunshine never seemed enough to make up for them. Diego didn't seemed to have moved; his snores certainly hadn't changed rhythm. If he ever felt rested enough, he'd given no sign of it. His breakfast of bread, olive oil, and wine (the latter two imports from Spain) is capped off by a visit from his captain’s servant Enrique, summoning him to an immediate meeting with said captain. Enrique is so brilliant and diligent a servant as to inspire envy in De Vega, who is saddled with the useless Diego. This does not prevent him from answering the summons immediately, of course. quote:"Buenos días, your Excellency," Lope said as he walked in. He swept off his hat and bowed. Guzman needles De Vega for his late return the night before, and the subject turns to the failing health of Spain’s dying monarch Philip II, and a mutually insincere hope that Phillip III will match his father’s rule. This turns to De Vega’s plans for the day, which are to attend the theatre. Guzman wonders if this is really in the line of duty, or simply a desire to satisfy the literary interests of Lope De Vega. De Vega counters with the well reasoned argument that he can gauge the mood of the common Englishman while standing incognito in the crowd, and chatting with the actors afterward could bring more insight still. quote:"Some of them indeed have connections with their patrons." Guzmán gave the word an obscene twist. But then he sighed. "Still, I can't say you're wrong. Some of them are spies, and so . . . and so, Lieutenant, I know you are mixing pleasure with your business, but I cannot tell you not to do it. I want a full report, in writing, when you get back." De Vega makes his way to the theater, envying the fact that the English have dedicated theatres at all, as opposed to the Spanish practice of performing in front of a tavern. He pays the cheapest price to stand among the groundlings, reasoning that he’ll hear more there than he would in the more expensive gallery seats. This is rewarded when he hears a conversation praising the now-burned Stubbes that stops just short of criticizing the Spanish. Philip II of Spain died of cancer in September 1598, meaning that concerns of failing health in 1597 are entirely reasonable by comparison to OTL. This, however, is another example of excessive parallelism. Much as with Isabella marrying Albert, there is a strong tendency for him to match things up to actual history even when the conditions changed dramatically. While the cancer that killed Philip in real life may have struck regardless, it is highly unlikely that it would strike in exactly the same way and time that it did historically. Likewise, there is a very real chance that Philip III would have grown up a different man in a Spain that had crushed all enemies. Failing to consider that could justly be considered lazy writing. quote:

quote:But Shakespeare, as de Vega had seen him do in other plays, used English conventions to advantage. Rosalind disguised herself as a boy to escape the court of her wicked uncle: a boy playing a girl playing a boy. And then a minor character playing a feminine role fell for "him": a boy playing a girl in love with a boy playing a girl playing a boy. Lope couldn't help howling laughter. He was tempted to count on his fingers to keep track of who was who, or of who was supposed to be who. After the play, De Vega makes his way backstage to meet with the actors, which is so routine a behavior that the guards know him by name. There is a bit of comedy when he runs into somebody’s wife backstage and responds gracefully, only to have his lecherous reputation mocked by the company clown, Will Kemp. He finds Shakespeare having a chat with Christopher Marlowe, and the three of them start to talk about the theatre. The choice of Lope De Vega to serve as Shakespeare’s foil is a good one. De Vega’s connection to the theatre makes their contacts eminently natural in a way that any other soldier would not have, and his status as a literary giant rivaling Shakespeare makes the image a striking one. Chapter 1, Part 3: Shakespeare. Late that evening, Marlowe rants about De Vega’s long presense, and mocks Shakespeare for calling the Spaniard a harmless theatre nut. Shakespeare responds with a dig at Marlowe’s love life. quote:Shakespeare stood several inches taller. He set a hand on the other playwright's shoulder. "However long he lingered, he's gone now, Kit. He's harmless, or as harmless as a man of his kingdom can be. Mad for the stage, as you heard." Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) was another of the giants of Elizabethan theatre. His works were a great influence on other playwrights of the day, most notably a certain William Shakespeare. Indeed, he is one professed candidate for the “true author” of some of Shakespeare’s plays by theorists who lean in that direction. Concrete information about him is scanty. Speculation that he was an atheist, a Catholic, and a spy can be traced to his own era, and rumors of his love of boys appears shortly after his death, although none have been solidly substantiated. He died of a knife in the head during a fight with a man named Ingram Frizer. After further prompting from the tired tireman, the two carry the argument out into the streets. At this point, Shakespeare prods Marlowe for whatever it is he didn’t want to talk about in front of De Vega. Marlowe wants Shakespeare to meet with a business acquaintance of his, to which Shakespeare agrees. Marlowe, however, seems furious even after said agreement. After some discussion, it turns out that Marlowe is angry because said acquaintance wants to do business with Shakespeare instead of Marlowe. Realizing now that the business must be of a literary nature, and fully recognizing the extent to which Marlowe influenced his own work, Shakespeare offers to refuse the man, stepping aside to give Marlowe the job. Marlowe is surprised, but admits that Shakespeare really is better for the job, needling Shakespeare for being willing to stand aside. They part, with the guarantee that Marlowe will bring his friend to meet Shakespeare the next evening. Assuring his landlady that his late return was merely due to lingering after the play, and further assuring her that he’d have no trouble paying the rent, Shakespeare has a mug of ale before heading to dinner. quote:From the chest by his bed, he took his second-best spoon--pewter--a couple of quills, a knife to trim them, ink, and three sheets of paper. He sometimes wished he followed a less expensive calling; each sheet cost more than a loaf of bread. He locked the chest once more, then hurried off to the ordinary around the corner. He sat down at the table with the biggest, fattest candle on it: he wanted the best light he could find for writing. quote:

Thomas Phelippes (1556–1625) was a linguist and intelligence officer of the English government. He is most famous for playing a key role in unearthing the plot to kill Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary I. If we accept that Marlowe was a spy, it would be extremely likely for him to know Phelippes. This section is more setup, and more interesting as a sort of slice-of-life bit than for plot reasons. The final sentence is a good cliffhanger, leaving us with the mystery of what exactly they want Shakespeare to do, and how a common playwright could play any role in saving England. Gnoman fucked around with this message at 01:52 on Nov 8, 2019 |

|

|

|

Epicurius posted:It's kind of interesting that Turtledove is making the two viewpoint characters both playwrights...one English and one Spanish. Thank you. I fully intended to cover this, and thought I had. 1597 Chapter II Part I: De Vega We open this chapter with De Vega speaking with Enrique before a meeting with Guzmán in response to his report on the play he attended. Enrique is full of praise both for De Vega’s report and for Shakespeare himself. After chit-chat along these lines, De Vega is brought into Guzmán’s office. quote:"Oh, no doubt, no doubt, but Enrique will make too much of himself." Tapping the report with his forefinger, Guzmán got down to business: "Overall, this is a good piece of work, Lieutenant. Still, I need to remind you again that you visit the Theatre as his Majesty's spy, not as his drama critic." De Vega acknowledges meeting Marlowe, stating that he was merely there as a literary critic. Guzmán counters that Marlowe is a very dangerous man, known to keep company with rogues of all sorts. Knowing too many of the wrong kind of people means that Marlowe probably is the wrong kind of people, and the Inquisition has investigated him repeatedly. This naturally turns to Marlowe’s association with Shakespeare, and inevitably to Shakespeare himself. quote:

Guzmán acknowledges this, but still considers this to be a matter worth investigating. Guzmán tells De Vega to take his report to an Englishman in Westminster who is an important part of the Spanish administration of the country, assuring him that the Englishman speaks perfect Spanish. This gun didn’t take long to fire. We saw last chapter that Shakespeare has been recruited in some plot against the Spanish, and De Vega was a perfectly placed agent to fight against said plot. Spurring the inquisition to suspect guilt-by association and thus giving De Vega a vague suspicion that something is wrong is a textbook way of bringing about the main conflict of the story, and it is hard to fault Turtledove’s use here. I think it is kind of a clumsy execution, however, particularly in timing. quote:A wan English sun, amazingly low in the southern sky, dodged in and out from behind rolling clouds as Lope de Vega rode through London toward Westminster. When he went past St. Paul's cathedral, he scratched his head, wondering as he always did why the otherwise magnificent edifice should be spoiled by the strange, square, flat-topped steeple. Not so much as a cross up there, he thought, and clucked reproachfully at the folly of the English.  The building De Vega is discussing is the predecessor to the current St. Paul’s Cathedral. Old St. Paul’s was famous for having a rather maginificent steeple – until 1561. In that year, the steeple caught on fire (probably due to a lightning strike), causing the entire thing to cave in. The roof was repaired, but no new steeple was erected. Restoration of the grand old building was begun in 1621, but halted by the outbreak of the English Civil War. Eventually, the entire structure was gutted in the Great Fire Of London in 1666. While reconstruction was technically possible, the immense cost led leaders to demolish the structure and build a new cathedral instead. quote:Lope couldn't tell exactly where that ward ended and the suburbs of the city began. He had thought Madrid a grand place, and so it was, but London dwarfed it. He wouldn't have been surprised if the English capital held a quarter of a million people. If that didn't make it the biggest city in the world, it surely came close. Phelippes and De Vega chat amiably about languages and the virtues of Captain Guzmán, although De Vega notices something peculiar about Phelippes as he explains his mission and hands over the report. quote:Phelippes took it. "I thank you. I am acquainted with Captain Guzmán. A good man, sly as a serpent." Lope wouldn't have used that as praise, but the Englishman plainly intended it so. He also spoke of the Spanish nobleman as an equal or an inferior. How important are you? Lope knew he couldn't ask. Phelippes went on, "Is there anything he desires me to look for in especial?" Here is a very interesting passage. Phelippes is not only on the side of whatever conspiracy is recruiting Shakespeare, but also a high figure in the occupation government. The obvious ploy for an author is to make it unclear who Phelippes is really working for – is he a rebel spy in the government, or is he an agent provocateur? Unfortunately, however, he is so blatantly covering for Shakespeare here that there is no mystery – if he was working wholly for the Spanish, or playing both sides for some reason, he’d have been much less blatant about protecting Shakespeare. This isn’t necessarily a fault in the writing – Turtledove might have decided that he didn’t want the readers to doubt, and simply wanted to demonstrate the reach of the conspiracy he hasn’t yet revealed. Chapter 2, Part 2: Shakespeare quote:When rehersals went well, they were a joy. Shakespeare took more pleasure in few things than in watching what had been only pictures and words in his mind take shape on the stage before his eyes. When things went not so well, as they did this morning . . . He clapped a hand to his forehead. " 'Sdeath!" he shouted. "Mechanical salt-butter rogues! Boys, apes, braggarts, Jacks, milksops! You are not worth another word, else I'd call you knaves." Shakespeare acknowledges the hit, but insists that his part is small and that the next performance would be a disaster if things don’t improve. Burbage insists that everything will be better when it comes to the afternoon’s performance, as they always are.  Richard Burbage (1567-1619) was the owner of two theatres in London, and an extremely prominent actor. Most of Shakespeare’s title roles were first played by Burbage, and he was also a talented artist – it is speculated that the most famous painting of Shakespeare was a Burbage work. quote:"Not always," Shakespeare said, remembering calamities he wished he could forget. They return to rehearsal for the afternoon’s production of Romeo and Juliet, particularly the scene where Mercutio is slain by Tybalt. Burbage is still upset about the argument, and a far better swordsman than Shakespeare is – he is stated to have fought against the Spaniards during the invasion, while Shakespeare is a poor swordsman even by stage standards. These two factors almost cause Shakespeare to be injured when it comes time for him to “die”. Shakespeare acknowledges that the scene went better, but that he has something to say about Burbage’s swordsmanship. quote:The other player chose to misunderstand him. Setting a hand on the hilt of his rapier, he said, "I am at your service." The afternoon performance went well, but the stage is pelted by the groundlings throwing stones at gentlemen who paid extra for a space right by the stage – and obscured the stage with thick clouds of tobacco smoke. Shakespeare is cleaning up and trading barbs with Will Kemp when De Vega enters. quote:"Were you I, you'd have a better seeming than you do," Shakespeare retorted. People laughed louder than the joke deserved. The biter bit was always funny; Shakespeare had used the device to good effect in more than one play. Will Kemp bared his teeth in what might have been a smile. He found the joke hard to see. quote:

De Vega accepts this, and wanders off to flirt with one of the nearby women. Noting that one of the hired actors is infuriated by De Vega’s advances, he decides that this is an opportune time to leave. He collects Burbage and heads out of the theatre, stopping to have a passed-out customer removed from the theatre to avoid him getting a free play the next day. Watching a woman slip and fall turns the subject to Will Kemp, and Burbage provides an excellent opportunity for Shakespeare to begin discussing weightier matters. quote:Shakespeare nodded. Kemp in particular had a habit of extemporizing on stage. Sometimes his brand of wit drew more mirth than Shakespeare's. That was galling enough. But whether he got his laughs or not, his stepping away from the written part never failed to pull the play out of shape. Shakespeare said, "Whether he know it or no, he's not the Earth, with other players sun and moon and planets spinning round his weighty self." The subject of the Inquisition allows Shakespeare to discuss the Spanish occupation and then, when Burbage expresses dissatisfaction with the situation, to bluntly ask if Burbage wants Elizabeth back on the throne. After some equivocation, Burbage finally puts it plainly. He’s an Englishman, not a Spaniard, and Shakespeare can go tell De Vega that if he wants to. quote:"You were an idiot to speak your mind to me, did you reckon I'd turn traitor," Shakespeare replied after some small silence of his own. Apart from that, Turtledove does a good job here illustrating the attitude of someone living in an occupied kingdom. Having to decide how far you can bend before you betray your true loyalties is exactly the sort of thing people would have to deal with in such a situation. They split off, Shakespeare going to his boarding house and Burbage to his home. Shakespeare muses that, were he to go home to Stratford as his wife insists upon he would avoid dealing with the Spaniards almost entirely, as they rarely go to the sleepy village. Unfortunately, London holds too much fame and money for him to be willing to do that. quote:When he walked into the house where he lodged, Jane Kendall greeted him with, "A man was asking after you today, Master Will." She remembers that the man gave the name of Nick Skeres, and that she told him to look at the Theatre, which is where Shakespeare is during the day. One of the other boarders, a man named Peter Foster, suggests that the man might be wanting to throw Shakespeare in jail, and that innocence means nothing if the man is paid. He then criticizes Shakespeare’s lack of a sword, as any threat isn’t likely to know Shakespeare has no idea how to use one, but would reckon that a large man like Shakespeare would be extremely dangerous in a fight, if properly armed. He heads off to his customary place for meals, where he dines on stewed eels. After he eats, he tries to do some writing, but has little success. [url=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Skeres[/url]Nicholas Skeres (1593-1601?) was a con man and government spy in this era. He was almost certainly a player in the plot to kill Elizabeth that Thomas Philippes helped unover, probably as a government agent. He was later dining with Robert Poley (another man involved in uncovering the plot), Ingram Frizer, and Christopher Marlowe when an argument between the latter two lead to Frizer killing Marlowe in alleged self-defense. He was later involved with the rebellion of the Earl of Essex in 1601 and thrown in prison, where he is believed to have died. quote:Tonight, though, his own misgivings were what kept interrupting him. It was not a night when he had to worry about forgetting curfew. That he got anything at all done on Love's Labour's Won struck him as a minor miracle. The play Shakespeare is working on is a bit interesting. There is no extant play known as Love’s Labour’s Won, although there are references to such a play existing in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. While it is possibly a lost work (perhaps as a sequel to Love’s Labor’s Lost), it is also possible that it was an early title of an older play – candidates include The Taming Of The Shrew, Much Ado About Nothing, or As You Like It (which, of course, is the play De Vega attended in Chapter I). Chapter 2: Part 3: De Vega quote:The two actors--actually, the two Spanish soldiers--playing Liseo and his servant, Turín, appeared at what was supposed to be an inn in the Spanish town of Illescas, which lay about twenty miles south of Madrid. The one playing Liseo hesitated, bit his lip, and looked blank. Lope de Vega hissed his line at him: "¡Qué lindas posadas!" La Dama Boba (literally “The Silly Lady”, one English title is The Lady-Fool) is a comedy by Lope De Vega. The real de Vega didn’t write this work until 1613, rendering this as a potential anachronism. The different circumstances can excuse this – he simply wrote it earlier in this timeline- but the lack of any “I changed it on purpose” signposting makes me suspect this was an error by the author. The furious de Vega pushes the two soldiers too far when he compares them negatively to the English actors he has been working with. quote:

quote:"Your Excellency, I am always devoted to duty," Lope said. It wasn't strictly true, but it sounded good. He added, "And the powers that be have been kind enough to encourage my plays. They say they keep the men happy by giving them a taste of what they might have at home." Diego is, of course, asleep, and is far from enthusiastic about his new job. De Vega threatens him into the job at swordpoint, neither of them absolutely certain that the threat won’t be carried out. De Vega further informs him that, should Diego refuse to act he will be dismissed from de Vega’s service. Diego thinks this might not be so bad as he could always find another master, but de Vega cuts that thought off. quote:

Another slice-of-life chapter, which seems to exist only as a nod to the real De Vega’s literary status. This isn’t a bad thing, and contributes to building the character, but it could be called padding. De Vega doesn’t come off too good here – aside from his offhand remark about Diego being just a little above a slave, threatening an employee with a sword (and sword-wielding Scotsmen!) because he doesn’t want to do something that is well beyond his usual duties is a bit harsh. Chapter 2: Part 4: Shakespeare Shakespeare is walking out of a poultry shop where he has just bought new feathers to make into pens when a man approaches him and hails him by name. quote:He did get recognized away from the Theatre every so often. Usually, that pleased him. Today . . . Today, he wished he were wearing a rapier as Peter Foster had suggested, even if it were one made for the stage, without proper edge or temper. Instead of nodding, he asked, "Who seeks him?" as if he might be someone else. quote:

.jpg) William Cecil (1520-1598) was by far the most important advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. He was the primary architect of English foreign policy in the era, and was the primary player in establishing the primacy of the Church of England and the persecution of England’s Catholics. He was also a major proponent of building up the Royal Navy as a guardian against Catholic powers. He died in 1598 of a stroke or a heart attack. Given his staunch anti-Catholic policies and his personal prestige, Cecil is an obvious threat to Spain’s control over England. It is thus incredibly unlikely that Philip would have him spared. To use a historical analogy, it would be like having a victorious Hitler leave Churchill alive while executing most other British politicians. Cecil orders Shakespeare and Skeres to sit, and informs them that the health of Philip II is failing, as is his own. Fortunately for England, Cecil’s son Robert is a better man than his father (according to Cecil) while Philip’s son is less able than Philip is. After some praise of Shakespeare’s play, Cecil informs Shakespeare that he is to deal the Spanish a heavy blow when Philip dies. quote:The gesture served well enough. Lord Burghley chuckled again--and then coughed again, and had trouble stopping. When at last he did, he said, "Think you not that, on hearing of Philip the tyrant's passing, our bold Englishmen will recall they are free, and brave? Think you not they will do't, if someone remind them of what they were, and of what they are, and of what they may be?" After this, Cecil switches to Latin, which Shakespeare can understand well enough. He asks Shakespeare if he had ever read the Annals of Tacitus. quote:

Shakespeare sees quite well – the possibilities are so obvious that he practically aches to go start writing. More importantly, he sees what Cecil wants him to write. The Annals Of Tacitus is a historical account of the Roman Empire from the years AD 14 through AD 89, not all of which survives today. [url= http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Tacitus/Annals/14B*.html] Book 14, Chapter 29-37[/url] describes an Briton uprising under Queen Boudicca that inflicted a heavy defeat on the IX African Legion and seized London, killing thousands of Romans before a larger and more prepared force returned the defeat, prompting Boudicca’s suicide. Quite obviously, Cecil wants the audience to make a connection with the Romans invading Britannia with the Spaniards that invaded England. Shakespeare is confident, but sees difficulties. Cecil’s promises of everlasting fame and an immortal place in history move him, but he persists in his explanations quote:

Cecil accepts this as a serious risk, but Shakespeare isn’t finished yet. Not only is it necessary to trust the entire company with the secret, but there must be many secret rehearsals, not to mention costumes. Cecil’s suggestion of skipping some of it is met with approval by Shakespeare, as long as Cecil wants a botched play that everybody laughs at. quote:A wordless rumble came from deep within Lord Burghley's chest. "You show me a sea of troubles, Master Shakespeare. How arm we against them? Here you must be my guide: you, not I, are the votary of this mystery." More quotes from Hamlet in this exchange. Shakespeare’s doubts are killed abruptly by a simple question from Cecil - “Would you see England free again?”. Faced with it directly, Shakespeare agrees. Still, he can’t get started immediately as Cecil wants him to. quote:Shakespeare didn't scream, but he came close. "My lord," he said carefully, "I am now engaged upon preparing a new play for the company, and--" So, now we know the plot. The idea of using a play to spark a rebellion is inspired (according to the afterword) by the 1601 Essex's Rebellion against Elizabeth I, which was intended to put the court in the control of the disgraced Robert Devereux, earl of Essex. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men (Shakespeare’s company!) was paid an impressive sum to perform Richard II in an apparent bid to gain support. The rebellion was broken up quite handily, and the company was not held in suspicion as part of it. It is interesting to note that Turtledove did apply the butterfly effect in the name of Shakespeare’s theatre company. The historical company was Lord Chamberlain’s men under the patronage of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon. Carey was not only a loyal servant of Elizabeth I, his position of the Captain of the Honourable Band of Gentlemen Pensioners made him her personal bodyguard at the time of the Armada. While it isn’t mentioned in the book as far as I can find, it is pretty obvious that Carey would have been killed during the invasion and thus in no position to sponsor a troupe of actors. Instead, Shakespeare’s company is Lord Westmorland's Men. This means their patron would be Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmorland. Neville was a devout Catholic who was a participant in the Rising of the North of 1569, which aimed to unseat Elizabeth, rescue Mary I, and put her on the throne. Fleeing to exile in Scotland, and later Flanders, Neville led a force of expatriate Englishmen as part of the forces intended to reinforce the Spanish Armada. In a world where the Armada succeeded, Philip II would have rewarded him greatly. Shakespeare is paid 50 pounds for his part, which is a lot of money. Based on the Bank of England’s inflation calculator, this would translate to £11,477.76 today – which probably underestimates things. Being paid that much for a single play would indeed be a good payday. Going back to my earlier statement about pacing, the first De Vega portion of this chapter would have worked better here – knowing exactly what Shakespeare is doing makes it much more interesting to see de Vega being sent after him. However, the nature of the plot means that using the Inquisition as a pointer was probably unnecessary. Sniffing out treason in the theatre is literally De Vega’s job, and having his suspicions raised by more organic means would have flowed better.

|

|

|

|

Chapter 3, Part 1: De Vegaquote:LOPE DE VEGA waved to a tall, scrawny Englishman in ragged clothes who stood, as hopefully as he could, by a rowboat. "You there, sirrah!" he said sharply. "How much to row us across to Southwark?" He pointed to the far bank of the Thames. Bear baiting was a popular blood sport in Elizabethan times, and continued in England until 1835. Today, there are a few regions where the "sport" is still practiced illegally, although the cost and difficulty of obtaining bears for the purpose limits it compared to other animal-fight practices. As practiced in England, it involved chaining a bear to a post and setting packs of hungry dogs on it. De Vega and his mistress watch a bear being tortured and killed by dogs for entertainment. After it dies, another bear is brought out to kill more dogs. quote:Lope and Nell had just left the bear-baiting garden when someone called his name from behind. It was a woman's voice. As if in the grip of nightmare, Lope slowly turned. Out of the arena came his other mistress, Martha Brock, walking with a man who looked enough like her to be her brother, and probably was. This is the only worthwhile part of this chapter. De Vega is publicly humiliated in a way that is certain to get back to his superiors and also many potential conquests. The bear-baiting is actually told fairly well, but it is still about torturing animals for entertainment. I suppose it is a worthwhile grounding in the setting, but it is pretty much irrelevant to the plot and really quite uncomfortable. Chapter 3, Part 2:Shakespeare quote:WILL KEMP LEERED at Shakespeare. The clown's features were soft as clay, and could twist into any shape. What lay behind his mugging? Shakespeare couldn't tell. "The first thing we do," Kemp exclaimed, "let's kill all the Spaniards!"  Will Kemp was a real person, and a fairly prominent actor in his era. Much less is known about him than Shakespeare or Burbage, but in 1600 he did, in fact, morris-dance from London to Norwich in 9 days (spread over the course of weeks). After some wordplay with Kemp, Shakespeare tries to sound out the loyalties of Jack Hungerford, the company's tireman (the contemporary term for the man in charge of wardrobe). As he will be essential to the presention of the new play, ensuring that he doesn't prefer the Spanish is essential. Unfortunately, Hungerford deflects the inquiry with ease. After a small part in the afternoon's performance of Marlowe's El Cid, Shakespeare leaves early to visit a bookseller. quote:Booksellers hawked their wares in the shadow of St. Paul's. Most of them sold pamphlets denouncing Protestantism and hair-raising accounts of witches out in the countryside. Some others offered the texts of plays--as often as not pirated editions, printed up from actors' memories of their lines. The volumes usually proved actors' memories less than they might have been. Apart from that, the problem of pirated plays was a very real one in this era, and it is the reason why most of the plays we have today are almost certainly corrupted to one degree or another. The bookseller does have a copy of Tacitus in stock, and tries to get Shakespeare to pay extra for a fine binding. Shakespeare, being of a thrifty inclination, preferrs to buy the book unbound. Even unbound, the bookseller is asking six shillings, After some haggling, they agree on 5 shillings sixpence, cutting 6 pennies from the price. At 20 shillings to the pound, this works out to almost £70 (~$90) in today's money. Comparing this to other prices, he could buy two threepenny meals at his normal eatery, or attend the theater (or a bear-baiting) six times. quote:

After everyone else has left, Kate trades some wordplay with Shakespeare, in which we learn that the two have been carrying on an affair. Mercifully, Turtledove spares us a sex scene here, jumping from a kiss to Shakespeare hurrying home afterward. Settling down to try some more writing, he is interrupted by Pete Foster, who turns out to be quite adept with lockpicks and let himself out of jail. The man is confident enough to sleep in his own bed before heading off to disappear, much to Shakespeare's alarm. Foster proves correct, as he is gone by morning with nobody coming to look for him. Chapter 3, Part 3: De Vega quote:"BUENOS DÍAS, YOUR EXCELLENCY," Lope de Vega said, sweeping off his hat and bowing to Captain Baltasar Guzmán. "How may I serve you this morning?" After fleeying his superior's office, he is briefly waylaid by Enrique, who is full of praise for La Dama Boba. De Vega warms to the praise, but he has to rush to the Archbishop. quote:"Thank you, your Eminence," Lope replied in the same language. He switched to English: "I speak your tongue, sir, an you have no Spanish." Welp. The Spanish have figured the whole thing out. Bold storytelling choice there! Naturally, the plot isn't going to unravel on page 99 of a 560-page book. Parson's suspicion of Shakespeare is based on the latter having been seen visiting a home of one of his betters (a mere playwright and actor has no business visiting the townhouse of a nobleman) and also in being seen with Skeres (who is the sort of ruffian no honest man would associate with. De Vega waves it off as Shakespeare being a friend of Marlow, and thus meeting many of the people Marlow meets - and Marlowe is not an honest man. The Archbishop is not convinced, and insists that De Vega investigate further. quote:Captain Guzmán had dark suspicions about Shakespeare, too. Lope had dismissed those: who ever thinks his immediate superior knows anything? But if Robert Parsons and Guzmán had the same idea, perhaps there was something to it. "I shall do everything I can to aid the cause of Spain, your Eminence," de Vega said. The book probably should have ended here, by internal logic. Shakespeare was already under suspicion from Kelley, and while De Vega's explanation covers Skeres, it does not explain why Shakespeare was visiting a house he had no business going near that happens to belong to a relative of a foe of Spain that was inexplicably left alive. Given that De Vega already has ample reason to be associating with Shakespeare (and thus serving as a threat to The Plot), this feels like an unnecessary narrative complication. Chapter 3, Part 4: Shakespeare quote:SHAKESPEARE KNELT IN the confessional. "Bless me, Father, for I have sinned," he said. The priest in the other side of the booth murmured a question he hardly heard. He confessed his adultery with the serving woman at the ordinary, his rage at Will Kemp (though not all his reasons for it), his jealousy over Christopher Marlowe's latest tragedy, and such other sins as came to mind . . . and as could safely be told to a Catholic priest. After going throuh his penance, he runs into Kate the serving woman leaving the confessional. After some slightly awkward (because he knows she probably confessed their affair just as he had) conversation, he heads to the boarding house, hoping to get some work done. As he does so, multiple people start noticing him. quote:He hadn't gone far before an apprentice--easy enough to recognize by his clothes, for he wore a plain, flat cap and only a small ruff at his throat--pointed to him and said, "There goes Master Shakespeare." He goes to dinner, and by some miracle he is able to write with great ease. He writes well enought that a disappointed Kate has to warn him in time to get home before curfew. The next morning, a large man greets him as soon as he leaves his lodgings. quote:"You are to come with me to Westminster," the man replied. "Forthwith." quote:"Bide here a moment," the Englishman with the deep voice said, and ducked into an office. He soon came back to the doorway and beckoned. "Come you in." Turning to the man behind the large, ornate desk, he spoke in Spanish: "Don Diego, I present to you Señor Shakespeare, the poet." Shakespeare had little Spanish, but followed him well enough to make sense of that. The Englishman gave his attention back to Shakespeare and returned to his native tongue: "Master Shakespeare, here is Don Diego Flores de Valdés." Flores wants Shakespeare to craft a memorial for Philip II. What sort of memorial? quote:The Spanish grandee snorted. One unruly eyebrow rose for a moment. He forced it down, but still looked exasperated; plainly, Shakespeare struck him as something of a dullard. That suited Shakespeare well enough; he wished he struck Flores as a mumbling, drooling simpleton. The officer gathered himself. "May the memorial, the monument, you make prove immortal as cut stone. I would have from you, señor, a drama on the subject of his Most Catholic Majesty's magnificence, to be presented by your company of actors when word of the King's mortality comes to this northern land: a show of his greatness for to awe the English people, to make known to them they were conquered by the greatest and most Christian prince who ever drew breath, and to awe them thereby. Can you do this thing? I promise you, you shall be furnished with a great plenty of histories and chronicles wherefrom to draw your scenes and characters. What say you?" Flores does not give Shakespeare the opportunity to refuse, and simply hands over a few of a hundred pounds. Combined with what he recieved from Cecil, this adds up to a rather tidy sum - but now he has to write a play for Spain and one for England. As he leaves, he spots Phillpes in a side room, and suspects that Phelippes is playing some sort of game. So the Spanish, who suspect Shakespeare of plotting against them, decide to derail any plot by simply giving him a comission to keep him busy? As a literary device, this could lead to a pretty clever plot, but it doesn't work so well in terms of real world logic. Gnoman fucked around with this message at 04:54 on Dec 23, 2019 |

|

|

|

CHAPTER IV, PART 1: De Vegaquote:"Shakespeare will write a play on the life of his most Catholic Majesty?" Lope de Vega dug a finger in his ear, as if to make sure he'd heard correctly. "Shakespeare?" De Vega returns to his rooms, where his servant Diegao is, of course, fast asleep. Kicking him awake, De Vega informs Dieago of his new duties, with a very stern warning that he will not tolerate Diego using this distraction to spend more time asleep. Well, at least the oddity of the situation is called out and somewhat justified. This is a very good way to ensure that De Vega is pitted against Shakespeare, as he's being assigned as Shakespeare's personal watchdog. quote:"Life is hard for a servant with a cruel master." Diego sighed. "Life is hard for any servant, but especially for one so unlucky." Lope De Vega is not only an rear end in a top hat here, he's a stupid rear end in a top hat. In two out of three chapters, he's fallen into mockery and embarassmant because he can't stop chasing women. This is a pattern. Chapter IV, Part 3 : Shakespeare. quote:RICHARD BURBAGE STARED at Shakespeare. "Tell it me again," the big, burly player said. "The dons are fain to have you make a play on the life of Philip?" Burbage reassures Shakespeare that the company knows that Shakespeare is too honest a man for such a ploy. Shakespeare objects that he'd die almost immediately if he were that honest, with Burbage insisting that Shakespeare is wrong. If Shakespeare were honest to all, he'd die very, very slowly. The conversation moves on to the play, with Burbage being rather fatalistic about the whole thing. It is Gods will which play the company will perform, and that's that. Shakespeare is disappointed and somewhat alarmed to realize that Burbage genuinley does not care which play goes on. The company will make money either way, which is what is important. Shakespeare considers this to be something of a security risk. Burbage's interpretation of events makes far more sense than what is really going on in the plot. This is a weakness - having multiple characters call out just how absurd a plot point is does not make the plot any less absurd, so it has to stand by itself still. I'm not entirely sure that this one does. Will Kemp, like Burbage, is concerned with King Philip only so far as making sure his own role is correct. quote:Will Kemp sidled up to him, still carrying the skull he'd use while playing the gravedigger come the afternoon performance. "You'll give me some words wherewith to make 'em laugh, is't not so?" he said, working the jawbone wired to the skull so that it seemed to do the talking. This really piths Kemp off, and the clown stalks off. Kemp's self-centered attitude does not reassure Shakespeare, and he becomes more and more convinced that the whole enterprise is doomed - the only mystery is who exactly will sell him out. This, inevitably, leads him to contemplate what will happen when his treason against Spain is discovered. quote:He wouldn't be burned alive, not for treason, or most of him wouldn't. They would haul him to Tower Hill on a hurdle, and hang him till he was almost dead. Then they'd cut him down and draw him as if he were a sheep in a shambles. They'd throw his guts into the fire while he watched, if he was unlucky enough to keep life in him yet. That done, they would quarter him and display his head and severed limbs on London Bridge and elsewhere around the city to dissuade others from such thoughts and deeds. This is an accurate description of hanging, drawing, and quartering, which was the maximum sentence for men (women were burned until 1790, when the sentence was reduced to hanging) accused of treason against the Crown in England from 1352 until 1814. After 1814, the sentence was reduced to hanging until dead and posthumous drawing and quartering, and in 1870 the penalty was reduced to simple hanging. The sentence was further reduced to life imprisonment with the final abolition of the death penalty in 1996. Shakespeare is shaken out of his dark reverie by Jack Hungerford, who is there to get him dressed to act as the ghost in quote:He did make a point of remembering the candle. Hungerford would never have let him live it down had he forgotten after their skirmish. He also made a point of carrying it carefully, so he didn't have to come back and start it burning again. Not out, brief candle, he thought. Light this fool the way through dusty gloom. More proof that this is Hamlet, of course. I do like the way he worked the reference to Macbeth into Shakespeare's internal monologue. Also, I like Lucy here. Shakespeare has a few appearances with no lines, with an assistant bringing him a fresh bowl of paper after each. Even here his bad mood persists. quote:He had no lines here, or in his next couple of appearances. He had but to stand, looking ominous and menacing, till his cue to stalk off, and then go below once more. One of the tireman's helpers crawled out to bring him another bowl full of bits of paper and a fresh candle. "You nigh gasted them out of their hose, Master Shakespeare," he whispered. The play continues until Shakespeare's role is done, at which point he flees from the smoke-filled area under the stage and aggressively begins to clean himself off. Burbage takes advantage of a scene he's not in to zip back and praise Shakespeare for his portrayal. quote:He washed again, then dried himself once more. "Better," Burbage said. "And the specter was as fine as you've ever given him." He imitated the gesture he'd urged Shakespeare to use. "Saw you how the audience clung to your every word thereafter, you having drawn them into the action thus?" Well, looks like he's still unhappy with Kemp. Marlow visits, and is immediately told to stop smoking his pipe. quote:"I will not, by God," Marlowe said, and took another puff. His eye swung to the beardless youth who'd played Ophelia, and who was now getting back into the clothes proper to his sex. "All they who love not tobacco and boys are fools. Why, holy communion would have been much better being administered in a tobacco pipe." Marlowe's line about tobacco and boys here is one that was attributed to him by the informer Richard Baines, who also accused Marlowe of evangelical athiesm, Catholicism, and blasphemy. Most scholars now consider this denunciation to be slander, and place little stock in it. This is the main source for the modern notion that Marlowe was homosexual himself, although there are some themes in his plays to support the notion. "Yseult and Tristan", more commonly rendered "Tristan and Iseult" or "Tristan and Isolde" is a legendary tragedy of the doomed romance between Tristan Prince of Cornwall and the Irish princess Isolde who is married to Tristan's uncle Mark, King of Cornwall. The legend is known to date back to the 11th century, although there is some evidence to suggest that the tale is even older. It has been cited as the inspiration for the tale of Lancelot and Guenivere in various versions of the Arthurian mythos, and the entire thing was inserted directly into the court of King Arthur by Malory. Probably the most famous adaptation today is the 1865 opera by Richard Wagner. It is an entirely plausible source for an Elizabethan play, but the notion of a Marlowe play derived from it appears to be an invention of Turtledove. Marlowe naturally knows about King Philip, and seems to be testing Shakespeare's loyalty to the plot. Shakespeare is spared from answering by the arrival of De Vega, in whose presence the plot must not be mentioned. Marlowe, as is typical of his behavior in this book, is acting like a boy playing spy games. He greets De Vega enthusiastically, praising the reception of La Dama Boba and regretting that he doesn't know enough Spanish to follow it himself. De Vega is delighted with the praise, but that won't stop him from interrogating Shakespeare. quote:The Spaniard turned to him. "You will tell me at once, Master Shakespeare: is the Prince of Denmark mad, or doth he but feign his affliction?" This bit of play concluded, De Vega gets down to business. He brings up King Philip and offers every assistance in the endeavour. Shakespeare tries to deflect, but Lope insists on playing a key part. Shakespeare is on the verge of erupting before Marlowe of all people quitely urges caution. quote:Shakespeare wanted to shriek. He couldn't tell de Vega everything he wanted to, or even a fraction of it. But . . . "Tacite, Will," Marlowe said quickly. This, of course, brings Burbage into the discussion, who demands to be informed what Marlowe was saying about him in Latin. The assurance that it was merely an admonition that the title role in King Philip belongs to Burbage and Burbage alone mollifies him, and he turns the whole thing into a dirty joke. Shakespeare ends the scene wondering how exactly he's going to plot treason against Spain with a Spanish officer stuck to him like glue. Chapter IV, Part 3: De Vega quote:LOPE DE VEGA couldn't have screamed louder or more painfully as a betrayed lover. He knew that for a fact; he'd screamed such screams before. This, however . . . "But, sir, you promised me!" he cried. "He is called John . . . Walsh." Captain Guzmán made heavy going of the English surname. "He dwells in"--the officer checked his notes--"in the ward called Billingsgate, in Pudding Lane. He is by trade a butcher of hogs, but he is to be found more often in a tavern than anywhere else." "May I find him in a tavern!" Lope exclaimed. "I know Pudding Lane too well, and know its stinks. They make so much offal there, it goes in dung boats down to the Thames." "Wherever you find him, seize him and clap him in gaol. We'll try him and put him to death and be rid of him once for all," Guzmán said. As de Vega turned to go, his superior held up a hand. "Wait. Don't hunt this, ah, Walsh yourself. Take a squad of soldiers. Better, take two. When you catch him, the Englishmen he has fooled are liable to try a rescue. You will want swords and pikes and guns at your back." [/quote] De Vega finds this advice dubious - alone he might be able to simply snatch the soothsayer and run. He follows orders nonetheless, and rounds up a squad of soldiers eager to stamp out a source of discontent. The sight of a squad of soldiers moving together draws jeers and a band of ruffians that attempt to hold them up. Before a fight can start, however, the mob decides that taking on armed and armored Spaniards while wielding clubs and wearing ordinary clothes is not a wise idea, and scatter. After getting lost, then getting lost again from bad directions, they find a Catholic who gives them good directions. quote:So did Lope. "We may find this Walsh and something to drink together," he said, "for I hear he prophesies in taverns." Lope heads into the tavern and orders ale, which he can say without a betraying accent. Sure enough, the butcher begins a long sermon on the evils of Spain, drawing heavily on the book of Matthew. quote:

Presented unedited because it is the first major action scene in the books. Turtledove does this, at least, fairly well - I could see this scene being played out in a movie quite easily, and he doesn't get bogged down in minute details. He does, however, underestimate the humble arquebus here. Any matchlock smoothbore is fairly inaccurate by the standards of a later age, but this mostly shows at battle ranges. At stone-throwing range, any soldier who's actually trying could probably hit a man. De Vega delivers his prisoner, and is granted permission to return to his primary duty at the theatre. Chapter IV, Part 4: Shakespeare Shakespeare's boarding house has a new lodger to replace the one who fled - an extremely poor and clumsy man named Sam King who keeps stepping on Shakespeare. Buoyed by good income from the theatre, which has been doing very well with Christmas approaching, he decides to give King enough money for a threepenny supper. We also hear of a second new lodger, a woman named Cicely Sellis who has hired an entire room from the stingy landlady, at what must be a fairly exorbiant cost. Shakespeare heads off to his own dining establishment with his manuscript and pen. quote:Shakespeare got out his writing tools and took them to the ordinary he favored. He was relieved not to find his fellow lodger there; King would have insisted on chattering at him when he wanted to work. Love's Labour's Won was almost done. He needed to finish it as fast as he could, too. For one thing, the company's patience was wearing thin. For another, he didn't know how long he had till Philip of Spain died. He would need to have both his special commissions ready by then, whichever one actually saw the light of day. Arriving back home long after curfew, he builds up the fire -much to the irritation of his stingy landlady- and continues to write at the same feverish pace. Gradually, however, he realizes that he is not alone. The new lodger, Cicely Sellis, has been watching him. As far as I can tell, "lambswool" is a term derived from a corruption of the Celtic phrase La mas ubal ("Day of the Apple Fruit"), and is a drink made by pouring hot ale (or cider) over pulped apples and spices - sugar, nutmeg and ginger. quote:"Give you good den," she said when he looked up. "I misliked troubling you, your pen scratching along so fast." She expresses desire to see the play when it is finished if she can get free from her business. On inquiring, he learns that she works for herself, and he would be wise to come to her if he wanted questions answered. quote:"Ah." He'd wondered what she did. No wonder she'd wanted a room all to herself. "You are a cunning woman, then?" He wouldn't say witch, even if they amounted to the same thing. quote:Mommet suddenly stopped purring. His fur puffed out till he looked twice his proper size. He hissed like a snake. A freezing draught blew under the door, making the hair on Shakespeare's arms prickle up, too, and sending a swarm of bright sparks up the chimney as the flames flared. She is confused, and professes to know nothing of what she just said, even after he repeats the words back. She uses this opportunity to retire to her rooms, cat following behind her. Shakespeare spends some more time trying to write, deeply disturbed. With little further progress, he heads to bed, confident that he will finish the play very soon. Turtledove notes in the afterword that there was a real woman named Cicely Sellis that was accused of witchcraft around this time, but that she is not the character in the novel. Turtledove's Sellis is a wholly fictional character. quote:His bedroom was dark when he went in. Jack Street's snores made the chamber hideous. Shakespeare knew he himself would have no trouble sleeping despite the racket; he'd had time to get used to it. How--indeed, whether--Sam King could manage was a different question. He finds sleep elusive, and lies awake for some time pondering what exactly Robert Cecil is planning and how likely it is to work; how he is to recruit the company to the plot without exposing it should a player balk; exactly what was going on with Sellis and where her strange warning came - from her, from God, or from Satan. Eventually, he sleeps. He wakes in the dark - the sun rises late and sets early in England near the winter solstice - and eats a bland breakfast. Of the lodgers, only Sellis remains. The landlady is beaming, and Shakespeare fears that this is a bad sign. Sellis must be paying a lot of money for that room, and he fears that this will lead to an increase in his own rent. quote:When he went out into the street, he found he would have no accurate notion of when the sun came up, anyhow. Cold, clammy fog clung everywhere. It likely wouldn't lift till noon, if then. Shakespeare sucked in a long, damp breath. When he exhaled, he added fog of his own to that which had drifted up to Bishopsgate from the Thames. As for the chapter as a whole, it is mostly a slice-of-life affair where relatively little happens. It isn't bad slice-of-life, but it doesn't advance the plot much.

|

|

|

|

Epicurius posted:Just as a note, the only actual Rennaisance story of Tristan I could find was one from Belarus. For whatever reason, for about 300 years, with the exception of a few pieces of work like The Fairie Queen, people mostly stopped referring to Arthurian legends, and it wasn't until the 19th century that they became popular again. This makes it a good choice for a non-historical work. There's no real author to snub, and it is entirely reasonable for there to have been a play on that subject. Chapter V, Part 1: De Vega quote:AFTER CHRISTMAS MASS, Lope de Vega and Baltasar Guzmán happened to come out of the church of St. Swithin together. Lope bowed to his superior. "Feliz Navidad, your Excellency," he said. Turteldove's completely wrong here - The Christmas season was a major holiday during the reign of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, filled with feasting, gift-giving, and parties. Shakespeare's own play Twelfth Night (1602) revolves around (and written as an entertainment for) the biggest and most popular festival day, Twelfth Night. The Anglican church continued to foster Christmas celebrations, with Charles I ordering noblemen to their estates in order to participate in the traditional role-reversal merrymaking. It was not until Charles I was defeated and executed by Cromwell's Parlementarians in 1647 that the Puritans took control of the country and banned Christmas until the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. After the ban was lifted, Calvinism continued to condemn the holiday, and the heavily Calvinist-influenced Presbytarians of Scotland were so adamant against it that it did not become an official public holiday in Scotland again until 1958. Turtledove seems to have conflated Puritiansim and Calvinism in specific with Protestantism in general. Also wrong: the name of the church. St Ethelburga-the-Virgin within Bishopsgate is one of the relatively rare structures from Shakespeare's time that was not destroyed in the Great Fire of London - the structure that was concencrated in 1250 stood until 1993, when it was among the structures that were effectively destroyed by a 1 ton bomb consisting of a mixture of ammonium nitrate and diesel fuel set by the Irish Republican Army. Half of the structure remained standing, and the exterior was rebuilt to the original plan, alhtough with a completely different interior. 1.jpg) He finds no difficulty getting directions to the church, and saves a great deal of effort by managing to get there just as Shakespere is leaving Mass. He hides, because the only possible purpose for being here would be the actual one - to spy on Shakespeare. He heads back to barracks to report, only to find Guzman already gone to a feast. He reports to Enrique instead. After Enrique recieves the report, De Vega heads to his room to write. To his astonishment, Diego is not sleeping - indeed, not even present. Chapter V, Part 2: Shakespeare quote:A RAGGED MAN on a street corner thrust a bowl of spiced wine at a pretty woman walking by. "Wassail!" he called. I am unable to find any exact match to this particular custom. Wassail (derived from Wæs þu hæl, or "be thou hale") was a traditional Christmas toast, with Drinkhail (Drinc hæl, "Drink And Be Healthy") as the response, but the closest contxt I can find is Twelfth Night wassailing - going door to door singing and presenting the wassail bowl for gifts in a predecessor to modern caroling. The drink here is also wrong for the period. In Shakespeare's day, the wassail bowl would have been filled with the same lambswool beverage seen earlier. A simpler mulled cider became common in later days, but the use of wine is primarily a part of modern revivals. In this case, it is possible that the use of spiced wine is a deliberate change that is supposed to reflect Spanish influence. He continues down the street, paying another wassailer for a different song. He pauses to buy his landlady a present - a new carving knife to replace one she had recently broken the handle on. quote:He strode past a cutler's shop, then stopped, turned, and went back. The Widow Kendall had broken the wooden handle on her best carving knife not so long before, and had complained about it ever since. She kept talking about taking the knife to a tinker for a new handle, but she hadn't done it. Like as not, she never would get around to doing it, but would grumble about what a fine knife it had been for the rest of her days. A replacement, now, a replacement would make her a fine New Year's present. quote:Showing Marlowe he'd drawn blood only encouraged him to try to draw more. With a smile, Shakespeare answered, "I'm sure I shall. The treason trials under Tiberius, perchance?" Ever so slightly, he stressed the word treason. Hammet Shakespeare, the only son of William Shakespeare and twin brother to his daughter Judith, died at the age of 11 in 1596. The cause is uncertain, although there were known incidences of bubonic plague in the area around that time. This part I quite like - it humanizes Shakespeare quite a bit - in this passage, he's not a legendary playwright or a conspirator, he's a grieving father. Quite wisely, Shakespeare braves heavy snows that Sunday to make it to Mass - it is January 4 by the Spanish calendar, but December 25 by the English one. By going out of his way to attend Mass that day, he makes absolutely sure that there is no way anyone can claim that he was celebrating Christmas by the illegal calendar. On the twelfth day of Christmas two days later, he again visits the church and witnesses a play about the Christ child. quote:Shakespeare found the performances frightful and the dialogue worse, but the audience here wasn't inclined to be critical. In the Theatre, the groundlings would have mewed and hissed such players off the stage, and pelted them with fruit or worse till they fled. After the holidays, he heads back to the theater with his completed-at-last manuscript. Burbage refuses to even look at it until it had been proofread, cleaned up, and -most importantly- copied into legible handwriting by Geoffrey Martin, the company's prompter and playbook keeper. Martin is also working directly for the goverment censor, Sir Edmund Tilney, meaning that his cooperation is essential for the plot to go forward. Sir Edmund Tilney was, in fact, the Master of Revels and in charge of censoring stage plays - for Elizabeth I of England. I find it unlikely that the Spaniards would have left one of Elizabeth's courtiers in so vital a position quote:The prompter was about forty. He'd probably been handsome once, but nasty scars from a fire stretched across his forehead, one cheek, and the back of his left hand. The work he had--precise, important, but out of the public's eye--suited him well. quote:"Your pardon, Master Martin," Shakespeare said. "I do essay precision, but--" Martin comments on the character of Adriano di Armatio -a Venetian braggart- commending Shakespeare for not making him a Spaniard, which the Master of Revels would never tolerate. A bit of a historical joke here - in the actual play the character is Don Adriano de Armado, a Spanish braggart. Shakespeare pounces on this opportunity to sound Martin out, and asks how much he likes tiptoing around Spanish sensibilites. He does not get the answer he wants. quote:"Working with the Master would be simpler without such worries, no doubt of't," the prompter replied. "But you'll not deny, I trust, that heresy's strong grip'd yet constrain us had they not come hither. I have now the hope of heaven. Things being different, hellfire'd surely hold me after I cast my mortal slough." Shakespeare returns to the rest of the company in deep despair, to the point that Burbage notices immediatly and assumes that there is something wrong with the just-delivered play. Shakespeare clarifies for him, evoking a bit of "fun" from Will Kemp. quote:Someone clapped him on the shoulder. He jumped; he hadn't heard anybody come up behind him. Will Kemp's elastic features leered at him. Cackling with mad glee, the clown said, "What better time than the new year for a drawing and quartering? Or would you liefer rout out winter's chill with a burning? I'll stake you would." Burbage is quite concerned with the newly discovered security hole, at which Kemp mocks them both for not knowing that Martin was a devout Catholic. Kemp brushes off concerns that he might be speaking too freely too close to Martin with the assumption that the new play would occupy his entire attention. quote:"O ye of little faith!" Kemp jeered. "Dear Geoff's prompter and book-keeper. He hath before him a new play--so new, belike the ink's still damp. What'll he do? Plunge his beak into its liver, like the vulture with Prometheus. A cannon could sound beside him without his hearing't." Burbage and Shakespeare fume about Kemp, and discuss what to do about Martin. Clearly, the plot cannot go on with him present, but they can't simply fire him - he's too good at his job for that not to be suspicious. They decide to just have Shakespeare continue writing the play, and hope for aid. quote:A couple of evenings later, as the poet was making his way down Shoreditch High Street towards Bishopsgate after a performance, a man stepped out of the evening shadows and said, "You're Master Shakespeare, are you not?" The last name is not given yet, but this is Ingram Frizer. Fizer (15??-1627) was a companion to Christopher Marlow and Nicholas Skeres, and was not simply present the night Marlowe was killed. According to official sources, Marlowe's death was caused by Frizer stabbing him above the right eye with a dagger. Chapter V, Part 3: De Vega quote:"Surely, Señor Shakespeare, you know that his holiness Pope Sixtus promised King Philip a million ducats when the first Spanish soldier set foot on English soil, and that he very handsomely paid all he had promised," Lope de Vega said. "A million gold ducats, mind you." quote:Lope sprang from his stool and bowed low, sweeping off his hat so that the plume brushed the floor. "Say no more, sir. Your fellow poets and players would think less of you, did you write below your best. This I understand to the bottom of my soul, and I, in my turn, honor you for it. I am your servant. Command me." This would undoubtably be a formidible obstacle to dramatizing a man's life. This likely contributes to there being very few plays about Philip II - all excerpts from "King Philip" in this book are actually modified excerpts from Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus - a play that would already have been written by this time. This work is eventually interrupted by Martin, who caught a major plot hole in Love's Labours Won. This is enough to cause Shakespeare to dismiss De Vega for now, with plans to get back to it two days later. Unusually, he came on -and leaves on- a horse. quote:Riding through the tenements that huddled outside the city wall, Lope felt something of a conquering caballero. He'd seldom had that feeling afoot. Now, though, he looked down on the English. From literally looking down on them, I do so metaphorically as well, he thought. A man's mind is a strange thing. quote:"If there were an earthquake, it would swallow you as the whale swallowed Jonah, and you wouldn't even know it!" Lope bellowed. "Scotland--" Lope De Vega: Still an rear end in a top hat. Diego insists that everyone's saying the same thing about Guzman. De Vega is doubtful, but cheers up a bit when he realizes that Guzman would be disgraced and removed from his post if he really does prefer the company of men, which would be a benefit to De Vega. Still, he knows full well that Guzman had a mistress until recently, which he throws in Diego's face. After Diego insists that Guzman preferring Enrique would quite obviously cause the loss of a mistress, De Vega loses his temper and orders Diego to get to work, starting by cleaning De Vega's dung-covered clothing. He heads off to report to Guzman, only to be waylaid by Enrique, who wants to know what working with Shakespeare is like. quote: