|

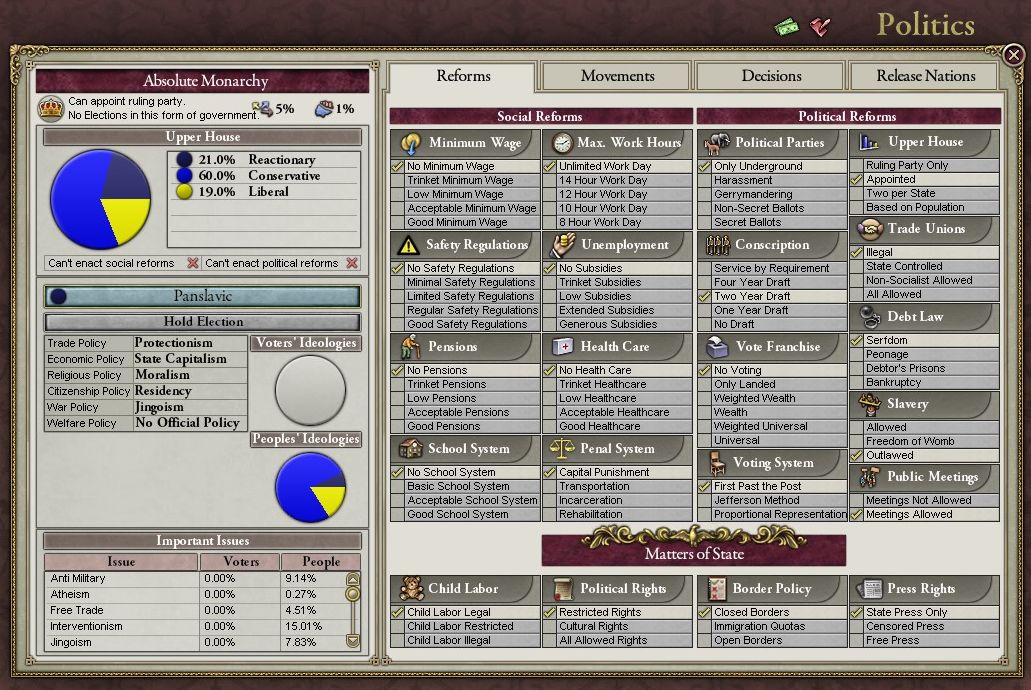

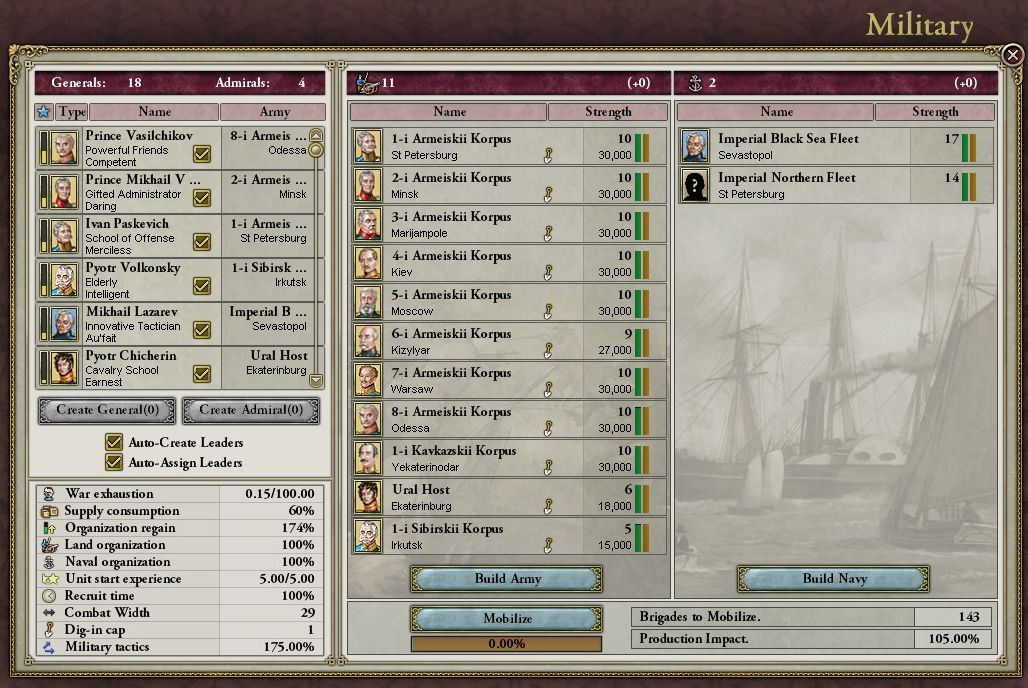

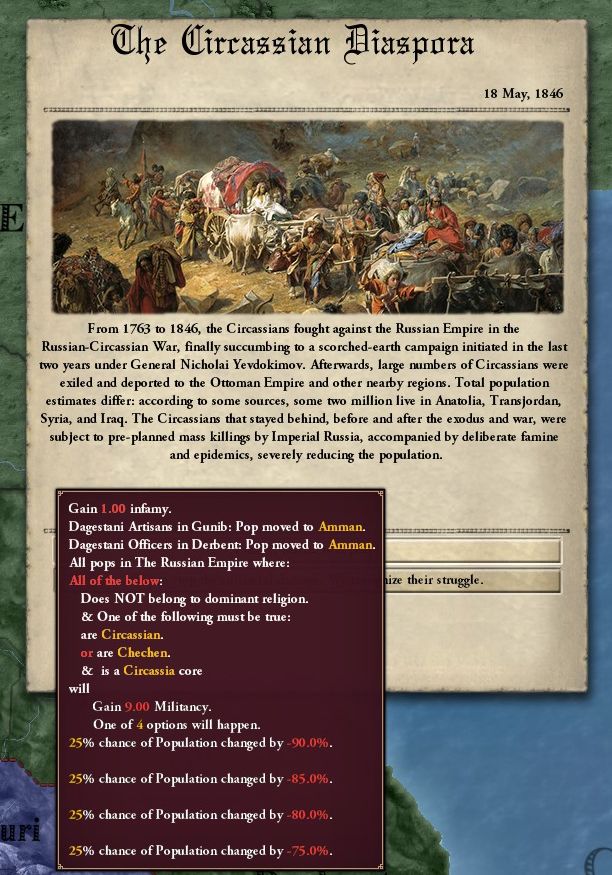

Serf's Up! Let's Play the Russian Empire in Victoria 2! Ah, the Russia that we lost... Ah, the nineteenth century. The height of the Russian Empire - a land of elegant dances, beautiful dresses, and heart-tugging poetry. For about 2% of the population. For the vast majority of the population of the empire, the 19th century was one of abject poverty and horror. Regular famines, disgusting levels of inequality, and a complete lack of education and medical services for the masses were just regular facets of everyday life for pretty much everyone. Outside the nobility, the church, and the rich traders, of course.  A serf's life Oh, and people were property. We're gonna be talking about them. Welcome to a character-focused Victoria II LP! It's gonna be fun! -- Wait, another narrative LP, don't you have like three unfinished ones already? I do! Those are, at best, on the backburner. Though I will finish the narrative part of ZunLP eventually, I have things to say. OldmenLP is pretty dead, though. Ok, so what's the deal with this one? Russian Empire world conquest? No. Gameplay-wise, I'm going to play the Russian Empire as arrogantly and oppressively as possible, to best match the way the way that abomination of a state was run. Narrative-wise, we're going to be following a family of serfs from a small estate near Nizhny Novgorod as they go through the turbulent 19th and early 20th centuries. They'll start out as serfs, and we'll see where it goes from there. People will be exiled to Siberia, fight in wars, *cough*revolt*cough*, and die. We'll track how generations change and adapt to the new world. Basically, if you've seen Heimat, it's that, but in Russia. Voting? If the Empire ends up having a parliament worth a drat, we might have some voting. At the moment, the will of the Tzar Emperor is absolute. Let's get this show on the road! -- Updates Generation 1 ----1.1. A Peasant Wedding ----1.2. A Good Deal ----1.3. New Bonds Supplemental Material Russian Background ----Supplemental 1. Russian Names ----Supplemental 2. A "Brief" History of Serfdom in Russia Kayten fucked around with this message at 00:53 on Oct 9, 2021 |

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 16, 2024 21:57 |

|

reserved

|

|

|

|

1.1. A Peasant Wedding Andrey Ryabushkin - A Peasant Wedding in the Tambovskaya Governorate (1880) 1836 - February 1st - Sergeevo pomestye, Nizhegorodskaya Governorate The sun slowly rose over the Sergeevo pomestye on a crisp February morning. Two hundred souls were yet to wake - after all, who needs to wake up this early in the middle of winter? And so, the serfs slept where they could: the young on the benches, and the elders on the stoves, where it was the warmest. All slept, except one.  Even if Avdotya Ivanovna tried to sleep the night before her wedding, she wouldn't be able to. For most serfs, their wedding was one of the highlights of their lives: their whole family coming together to wish them well in their union. But Dunya didn't have a family, not in any traditional sense. Her mom died along with her newborn baby sister near ten years ago, and her dad hasn't been the same since. Last summer, the drink caught up to him, and he passed out in a small puddle, drowning. Dunya was alone.  The pomestye helped her out, of course. Her dad's izba was in terrible shape even when he was alive, and with him gone, it threatened to collapse at any moment. This is when Bogdan Arhipovich started visiting more often. Bogdan was good with carpentry, because he had no other choice: he was orphaned at 10, and had to pull his own weight from a young age. So little by little, Bogdan fixed up her izba, and made his overtures clearer and clearer. And it's not like he was a bad man: he worked hard, the rest of the pomestye loved him, and unlike her father, didn't spend most days drunk. It's just that, well, she just didn't feel that way about him. Or any man in the pomestye, really.  Dunya sat by the window, staring out into the woods, her mind racing in a thousand directions. Her meditation on her wedding day was interrupted by the door swinging open. Her friend, Anfisa Kuzmichnina, came in, rubbing her hands for warmth. "Dunya! God almighty, you look like you didn't sleep at all!" "Fisa, I don't think I can do this. How can I stand in front of all those people, in front of God-" "Oh, Dunya, every woman feels like this! I went through this, my mother went through this, YOUR mother, may she rest in peace, went through this. You just need to take it one step at a time, and before you know it, you'll be a wife. Now get up, we have to get you dressed."  Reluctantly, Avdotya stood up, getting ready for the ritual upon ritual of the wedding day itself. Anfisa ran around her, slowly putting layer upon layer of light cloth on the bride. "Almost ready, Dunya, hold still, I need to stick oberegs to you." "Really, Fisa? I-" "Of course really! We need to make sure no one can jinx you!"  Avdotya sighed, but Fisa really was the expert here. Her father was the local priest, so she grew up hearing about all the prayers and oberegs you'd need to protect yourself. And a wedding was a fragile thing: a wrong glance at the bride could curse the whole affair! So Fisa filled the wedding gown with blessed needles, whispering her prayers over each one. The final obereg was a small pouch with a prayer written by her father - one of the very few people for miles around who could write. It hung from Dunya's neck. "There, as safe as you could be! Come now, to church!" ---  The small church that serviced Sergeevo and a few other pomestye in the area stood in an open field, with the priest's home nearby. A dirt road connected it to the outside world. A caravan of sleds pulled by horses carried the wedding party to the church: first Bogdan and his brother Osip, then Avdotya by herself, and finally Anfisa, her husband Yelisey, and her sister Marfa.  Fisa and Marfa's father, Kuzma, greeted the wedding train. As was tradition, Bogdan poured him a cup of a strong nastoyka and gave him a piece of pie to chase it. The father invited him inside the church, and they were married under the eye of the Lord. ---  After the crowning and common cup and the candles and the rings, the wedding train returned to the pomestye. By now, the rest of the serfs were up, and ready for the celebration. It was, after all, a great occasion: two orphans were orphans no longer!  The newly-minted couple's izba couldn't fit all the guests, so most of them came and went. Bogdan and Dunya sat in the main corner by the icons, and played host. Villager after villager would come in and demand to share a drink the new husband and his wife. Bogdan indulged them, cracking a joke for every man, while Dunya smiled, shook her head, and kept track of how often the jokes repeat.  Outside, Osip leaned against the izba wall to take a breath or two. Unlike his brother, he was never good with people. When their father died, Bogdan was only three years old. Osip was nine, and had to provide for the family. So he took his father's rifle and learned to hunt. He liked it in the woods: it's not that it was that much quieter than the pomestye, it's just that there was a lot less meaningless noise.  Perhaps the only person who could relate to Osip in the pomestye was Yelisey. A small river ran nearby, and he spent his life fishing. His craft required him to be patient and quiet, bringing him closer to Osip than anyone else around. Now too, he came out of the izba to take a break from people.  He leaned against the wall next to Osip. They stood for a few minutes in silence, staring at the stars. After a while, Yelisey rubbed his hands and spoke. "Cold out." "Yep." "You take a look at Marfa today?" "I did."  "My wife's sister has grown into a fine woman, hasn't she?" "She has." "And she's been eyeing you all day." "Didn't notice." Frustrated, Yelisey gestures at the izba, then at Osip, then back at the izba.  The door swings open, and Marfa herself comes out. The young woman heads over to the pair.  "Yelisey, Fisa's looking for you. Something about the sleds." He nods and heads to the door. Before going inside, he gestures at Marfa once again.  "Osip." "Marfa." "Haven't seen you around the church much lately." "Lots of work. Good time for hunting." She played with her braid, continuing the conversation.  "I hear you bring lots of furs to the pomestye." "I do. The barin takes most." "Oh, I see there's a small hole in your pants. You know, I could fix that." He looked at his pants. "Will fix myself. Thanks." Undeterred, she continued. "And I can keep a house."  "Good skill to have." Marfa has had enough. She stomped her foot. "Well, you're an idiot!" She stormed off towards the izba. Osip stood there, dumbfounded.  Sleigh bells rang out by the gate. A fat man in his fifties dressed in rich furs got out of the sled, and waddled towards the izba. Konstantin Aleksandrovich Gromov, the pomeschik of Sergeevo and the owner of all the men, women, and children in it, has arrived. His teenage son Mstislav followed behind him, looking at his surroundings with disdain.  Pomeschik Gromov opened the door, and the celebration inside ground to a halt. The quite drunk wedding party jumped to their feet and bowed. "I see there is a wedding happening, and I was not invited." Bogdan came over to the barin, bowing every few steps.  "Barin, this is a small affair, you see, we're both-" "I have not come here to punish you, man! Tell me, who are the lovely couple?" "Well, barin, I'm Bogdan, Arhip's son, and this is my wife", he said, gesturing at her to come over. "I'm Avdotya, Ivan's daughter, barin." "And where are Arhip and Ivan? Should they not be here celebrating this holy union?" Bogdan's face soured.  "My father died fighting the French, barin. Twenty years back or so." "Ah, I'm sorry, I did not know. Served the empire, did he? Is it just you, then?" "Me and my brother Osip, barin. Best hunter in the governorate. Could take a squirrel's eye out at 100 paces." "Best hunter, you say? I could use a good hunter. Bring him here."  "Already here", Osip said from behind him. "Is it true, then? About the squirrel?" He nodded.  "No choice. Need all the fur." "Indeed. Right, then, I will tell you what. You hit a squirrel in the head right now, and I will give the newlyweds a gift. Say, a cow. How does that sound?" Bogdan's eyes shot wide open. But Osip wasn't so quick to buy into the pomeschik's kindness.  "And if I miss?" "If you miss, I'll have you whipped. For wasting my time."  The room fell silent. A cow is a cow, though. "Deal." The man and his property shook their hands.  The wedding party moved outside, as Osip went to grab his father's rifle. It was by no means a new piece, nearly 30 years old at this point, but it was made in Tula, and kept in perfect condition. The rifle fed Osip, and he took care of it in return.  In front of his audience, dressed in furs to keep out the winter chill, Osip methodically loaded his father's rifle. The ritual complete, he went towards the treeline looking for a target. There, barely visible from where he was standing, a grey shape huddled for warmth on a grey branch. Osip quietly kneeled and took aim.  The wedding party had completely sobered up by now: too much was at stake. On the one hand, a cow would be a great help to the newlyweds. On the other, if the pomeschik was in a foul mood, a whipping could kill the man: either on the spot, or a few days later from blood loss.  The silence was broken with a single shot. The grey shape fell off the branch, completely still. Step by step, Osip made it to his quarry: a grey squirrel, shot straight through the eye. He smiled into his bushy beard.  "Here, barin." Gromov studied the dead squirrel. His serf performed admirably - a clean shot, most of the fur intact. "Very well. The next market day, I will buy the newlyweds a cow. And you, man, will be my son's personal hunter. Maybe you'll teach him a thing or two."  Osip bowed to Gromov and his son. "Very well, serfs! I leave you to your celebration!"  With the pomeschik and his son gone, the crowd erupted into cheers. Bogdan dragged his brother inside to get absolutely, positively wasted.

|

|

|

|

A very interesting approach! I look forward to reading more.

|

|

|

|

Always nice to see more Victoria 2 LPs!

|

|

|

|

Supplemental 1 - Russian Names Russian names are complicated. They don't quite get as long as, say, Roman or Spanish names, but they have their own quirks. So let's break them down. As an example to break down, let's take Дмитрий Иванович Менделеев (Dmitriy Ivanovich Mendeleev), the Russian chemist who came up with the periodic table of elements (and the correct vodka recipe). A general Russian name has three parts: your first name (имя, lit. "name"), your patronym (отчество, lit. "fatherness"), and your last name (фамилия, from Latin "familia" - dynasty, official clan). In this case, the first name is Dmitriy (or Dimitriy), from the Greek Demetiros. Lots of Russian names come from Greek via the church, which followed Greek liturgy. Also, the first name gets modified a lot for less formal conversation. Dmitriy can become Dima, Mitya, Dimchik, Dimon, and a whole slew of others. By the 19th century, there was a strict split between aristocratic and peasant names. Sometimes, different forms of the same name fell into different classes: Evdokia (from the Greek Eudokia) was an upper-class name, while Avdotya was left to the peasants. Most Greek-derived names went to the aristocracy (Konstantin, Dmitriy, Aleksandr), unless they were heavily "corrupted" by "peasant-speak" (Anfisa from Anthousa, Artyom from Artemios). Dmitriy's patronym is Ivanovich. The way patronyms are formed is as follows: you take your father's name (Ivan), and add a special ending to it (-ovich, -evich, or just -ich for men; -ovna, -evna, -ichna, or -inichna for women). Thus Dmitriy Ivanovich just means "Dmitriy, son of Ivan". Compare "bin/bint" and "ibn" in Arabic: Ibn Sina (Avicenna, the Persian medical scholar) means "son of Sina", though in this case, he wasn't Sina's son, he was his great-great-grandson, the full name included a few more bins and ibns. The first name-patronym pair was used as the polite way to address someone in upper society. So, if you met Mendeleev for the first time, you would call him Dmitriy Ivanovich. Peasants, however, would generally just use first names alone, or the patronym alone (for the elders). At best, you'd refer to an older man as Uncle + first name (Dyadya Vanya) or Grandpa + first name (Deda Lyosha), and an older woman as Aunt + first name (Tyotya Fisa) or Grandma + first name (Baba Dunya). Dmitriy's last name is Mendeleev. Most Russian last names end with -ov/-ev for men and with -ova/-eva for women. They generally come from first names (Ivanov - Ivan's), professions (Kuznetsov - Smith's), locations (Volgov - of the Volga river), nicknames (Men'shov - of the little one), or just pleasant-sounding words (Gromov - of the thunder). Mendeleev's last name’s origin specifically has a few versions, with a weird caveat that it's not his family's original last name. His grandfather's last name was Sokolov (of the falcon), but he got a new one after becoming a priest. Here's the thing about last names, though. Peasants in general didn't really use last names until the late 19th century, or even post-revolutionary times. My great-great-grandfather was only given one once he signed up for the Red Army. Serfs specifically sometimes were given a special "last name" derived from their owner. Whether these really counted as last names, I can't say, since they didn't cover a family as much as the whole pomestye, and would change if the serfs were sold. Instead of the usual -ov/-ev (-ova/-eva for the women) form, these would use an -ovskiy/-evskiy (-ovskaya/-evskaya) ending, like any other property. See: This is Demidovskaya cow (cow belonging to Demidov) = This is Demidovskiy man (man belonging to Demidov). In summary, our slowly growing family doesn't have a last name yet, and if it did, it would be Gromovskiy/Gromovskaya, at least until they get sold or inherited or given away as a dowry, or exiled to Siberia.

Kayten fucked around with this message at 02:01 on Mar 8, 2021 |

|

|

|

In at the ground floor and really enjoyed the first update. Honestly, I just want more victoria 2 in my life. It's not a particularly great game, but it's definitely the best 'simulation' paradox ever made and it really makes an amazing empty canvas. Feeling irrationally annoyed at the description of Avicenna as a medical writer tho, he was so much more than that. A true homo universalis

|

|

|

|

We really don't see enough LPs in and about Victoria 2 and its setting; will keep an eye on this.

|

|

|

|

Well consider me fascinated by this. Keep up the good work.

|

|

|

|

Definitely got too engrossed with reading the update and had to go back and actually look at the pictures of what's happening in the game a few times.

|

|

|

|

Getting some Sholokhov vibes from the narrative in a good way.

|

|

|

|

As a little girl I used to hear stories about how "Your great-grandmother fled over the border with the Tsar's bullets whizzing by her head!" My impression of late Tsarist Russia has only gotten worse since then. In other words, I expect this LP to be one hell of a trainwreck.  Do you plan on doing more informative posts about Russian history and culture? Ancestral grudges aside, I'm a shameless slut for history dumps. Don't feel like you have to push yourself though, a good LP is a heavy enough load as is.

|

|

|

|

excited for the serf number to go up and then collapse immediately to 0 upon a timely revolution

|

|

|

|

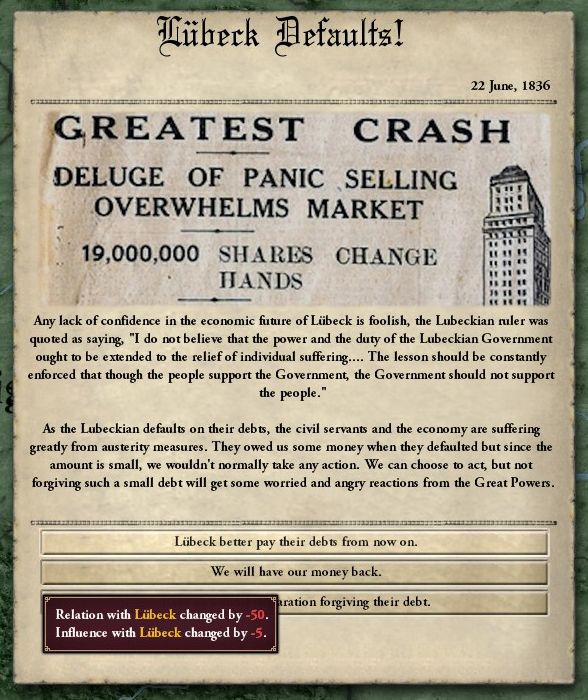

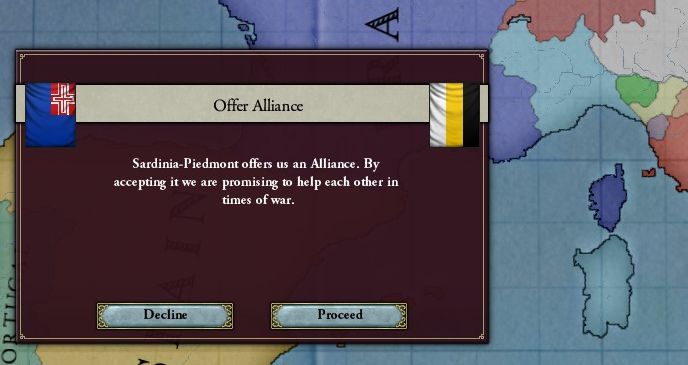

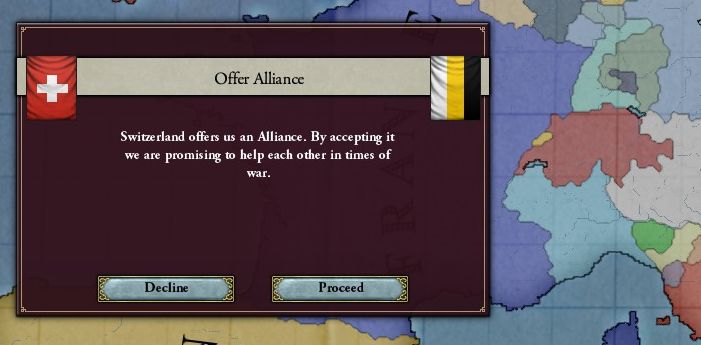

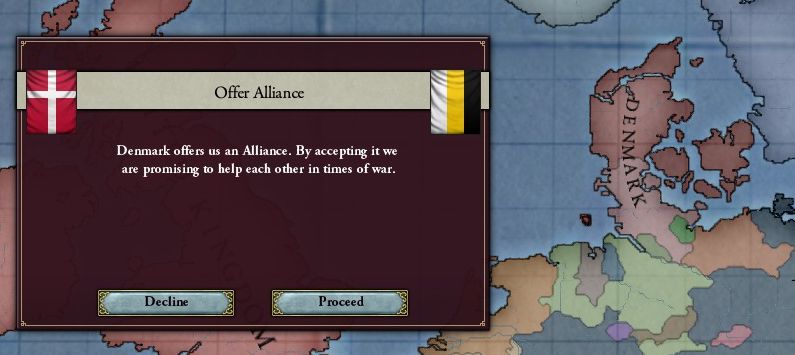

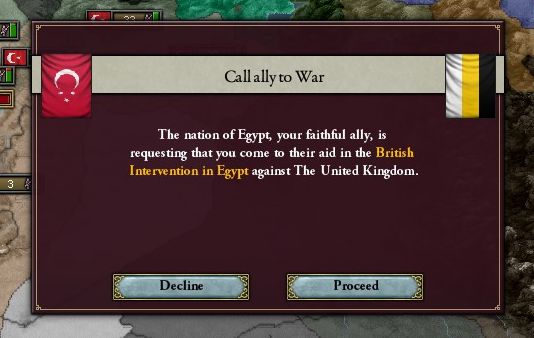

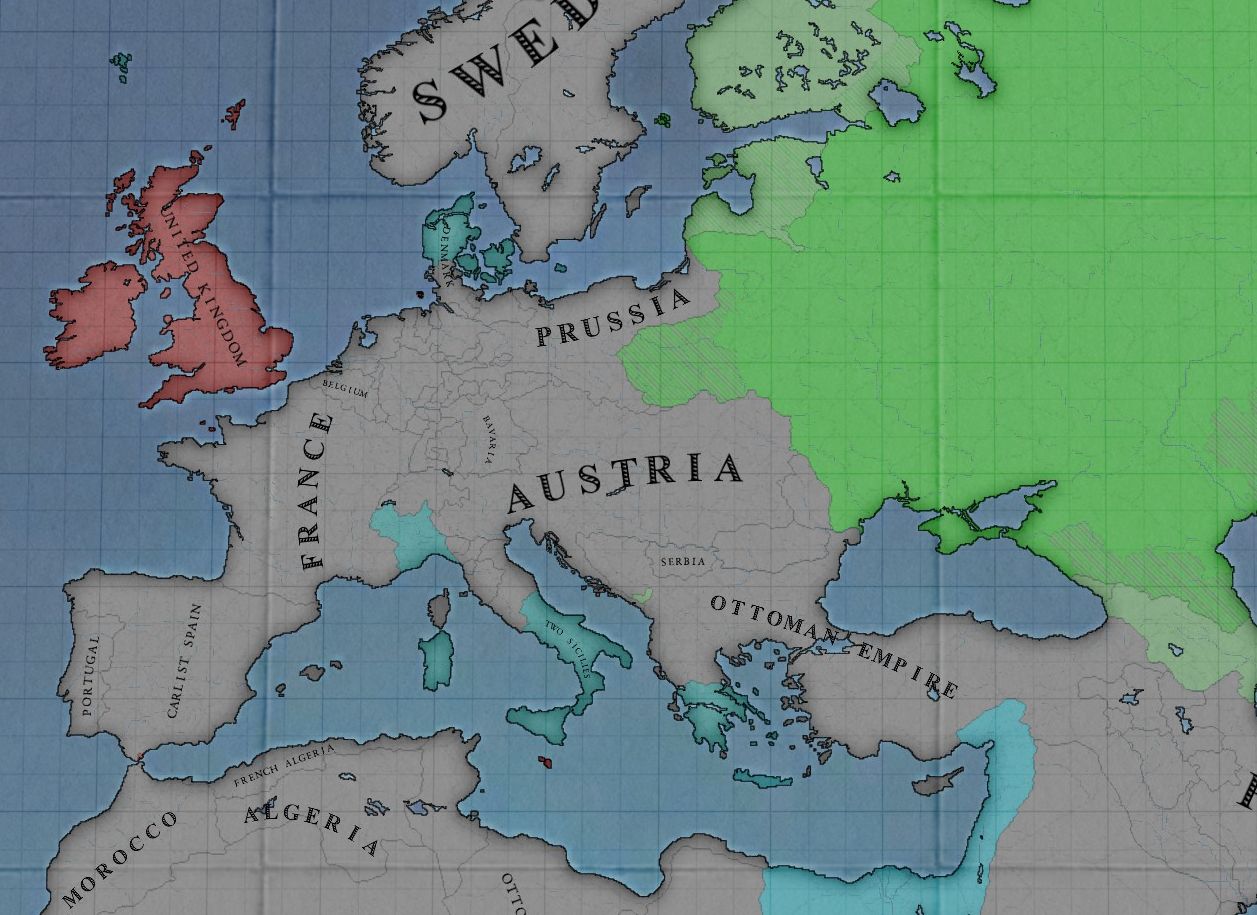

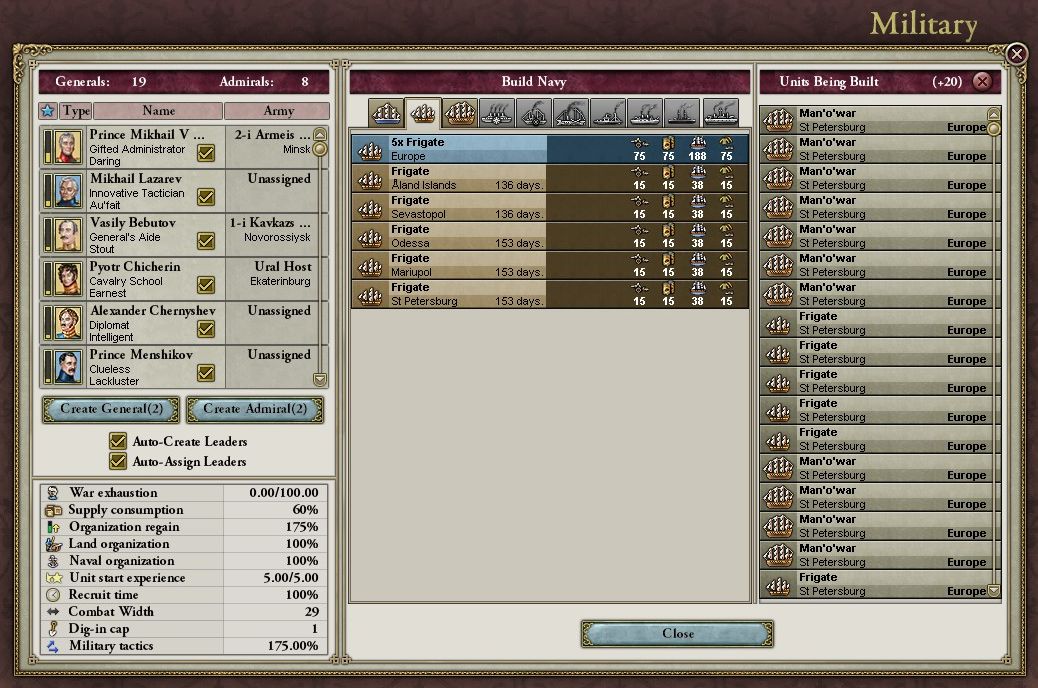

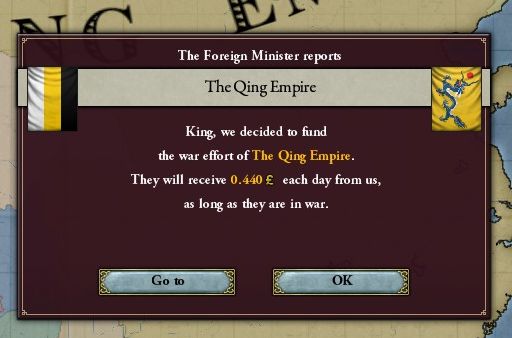

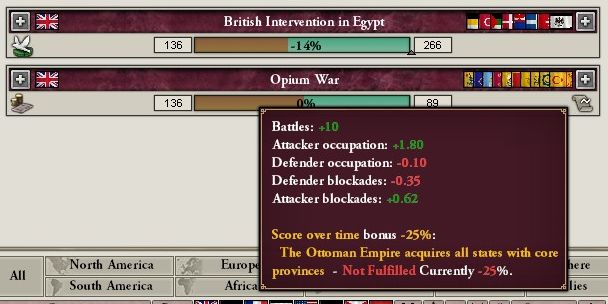

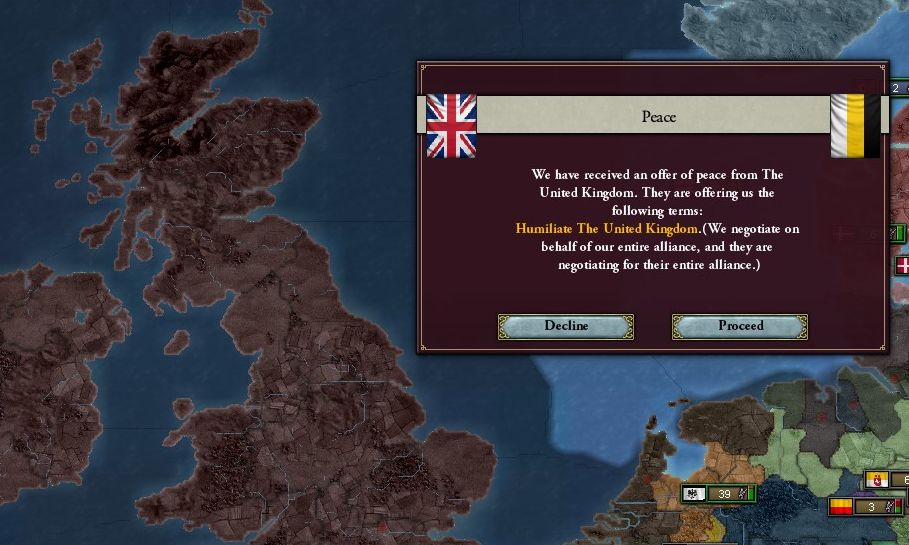

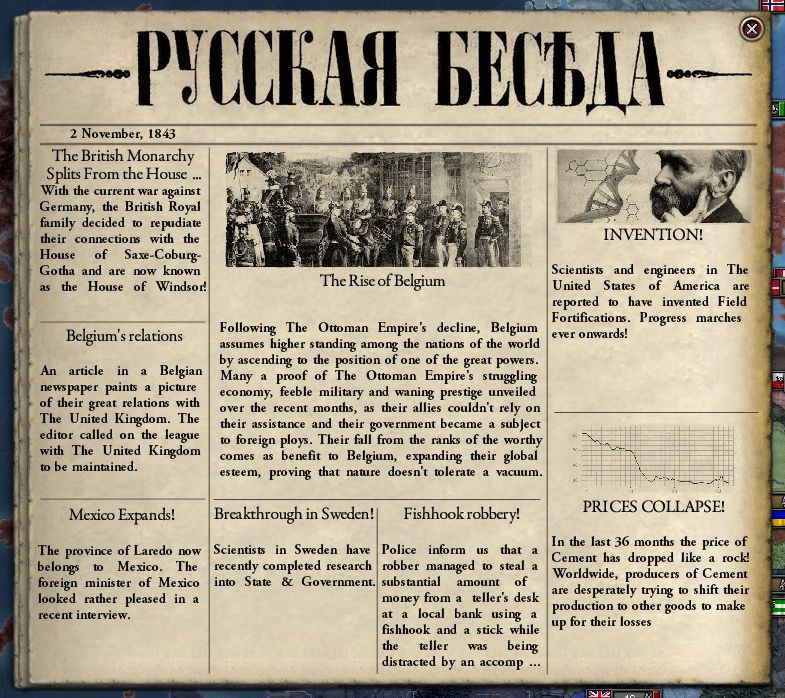

Oh boy, allied to the Ottomans and Greece! What could possibly go wrong??

|

|

|

|

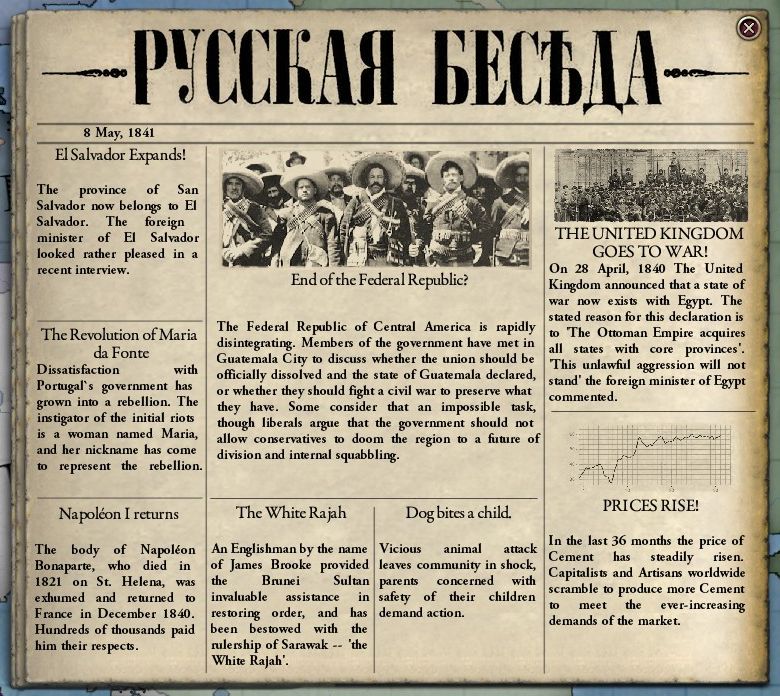

1.2 - A Good Deal Konstantin Trutovskiy - A Market in the Provinces (1893) 1840 - June 3rd - Outskirts of Arzamas, Nizhegorodskaya Governorate The old horse kept a steady rhythm, pulling the serfs' cart to the city. It was market day, and the men had things to sell. The trips to Arzamas weren't a common affair: the city was far from the pomestye, and they didn't always have the horses to spare. Osip was sorting the furs in the back, arranging the carcasses by colour. The smell stopped bothering him years ago. He rarely made the trip: he didn't really like people, especially in crowds, especially when they all tried to sell something. However, he had a few things to take care of this time. These furs were important.  His brother usually handled the sales; Bogdan loved wheeling and dealing. He could've been a good trader if his parents hadn't been serfs. Instead, he handled most trade from the pomestye's families. He didn't have to do as much hard labour, and he got more out of the sales than anyone else did. It was a good deal, though the frequent trips weren't kind to his back.  Unlike Osip, though, the rotting smell still annoyed him. He sat at the front, preferring the smell of the living horse to the dead animals in the back. "So, Osya, how many more trips do you think this work of yours is going to take?" "I don't know. A few. Depends on Arhip." "Arhip's a standup guy! He's kin, after all, even if he is city folk." "Hm."  Osip didn't like Arhip very much, kin or no kin. Yes, he was their cousin - his dad even named him after their dad - but there was something unpleasant about him. It wasn't the smell - couldn't avoid it, what with working at a tannery and all. No, Arhip had a sort of slipperyness about him. It's as if every conversation was a competition to him, and he just had to come out on top. But he did always hold up his end of a deal, and that's exactly what Osip needed right now. ---  The market was full of people from all over the area. After all, Arzamas was the second largest city in the governorate, after Nizhny Novgorod, though it was ten times smaller. Most of the sellers were local serfs and peasants getting rid of crops and animal products, but travelling traders did stop by every Wednesday as well. Osip hopped off the cart, and threw the sack of furs on his back. Bogdan stayed with the cart, calling the locals over to sample the fresh milk and eggs he had for sale.  Osip didn't have very far to go: across the market square, past the half-finished cathedral, and a few blocks to the tannery. The smell of death and chemicals around the factory was strong enough that even Osip had to hold his breath from time to time. He turned a few corners, and stopped by a side entrance. A young boy no more than 10 years old peeked out the door.  "Uncle Osip!" "Van'ka, fetch your dad." The boy disappeared for a few minutes. Osip took the time to set his sack down and look over the cathedral. To him, the massive church was another cousin: every time he came to the town, it grew a little taller, a little fairer, and a little closer to God. Most of the structure was already finished, and the workers spent their days tinkering with the domes. Inside, a swarm of artists painted their faith into its walls.  Osip's meditation on the cathedral was interrupted by a polite cough. His cousin was here. "Osip! Great to see you! What do you have for me this time?" Osip opened up the sack and laid the furs out on the ground. "Squirrels, mostly."  He split the furs into two piles. One had the finest squirrel carcasses: the cleanest shots, the least damage. The other had the less-perfect ones, and a few woflskins as well. Osip pointed at the second pile. "Your payment. As always." Arhip looked through it.  "Come now, Osya, do you take me for a fool? These are nowhere near the quality we agreed on! I'm taking a big risk here, you know." Osip took three good squirrel pelts and threw them on the second pile. "Satisfied?"  Arhip looked them over. "Now that's what I call fair." The pair wrapped the stacks up with rope. Arhip opened the door and nodded at his son.  By the time they were done packing the pelts up, Van'ka showed up with a small sack of gorgeous squirrel furs, cleaned and processed. Osip looked through the results and smiled into his beard. "You do good work."  "We ALL do good work, Osya. I'll see you in a month, yes?" "In a month." As Osip geared up to leave, Arhip stopped him.  "Oh, have you heard about the war? With the Englishmen." "Englishmen? Why?" "Why, because of the Turks, of course! Once again, the treacherous Englishmen are pushing them to war! My uncle died freeing them from the French, and this is how they repay us?" "Dad died at Grodno. Not a lot of Englishmen there."  "That's beside the point! We saved the world from the French, and now the English forget! Traitors and cowards to a man!" "Arhip. You see many Englishmen in Arzamas?" "I don't need to see them to know what they're like. You've never seen a Frenchman either!" "Careful, cousin."  "I mean no disrespect to your father, Osya. All I'm saying is that you and I know that the French are a murderous people who came here to kill every last one of us. And we didn't need to speak to a Frenchman to learn that." "Hm. And the Turks?"  "I don't know, something about Egypt. All I know is that the Tsar declared war on the English, and our brave boys will remind them about the glory of Russia!" "Right. More recruitment then?" "Maybe soon. God watch over you, cousin." "You too, Arhip." Heaving the new sack over his shoulder, Osip went back to the market. ---  The cart was full of new product: tools, cloth, ammo and powder, and even a few toys. Bogdan sat next to it, carving a block of wood with a small knife. Osip tossed the sack inside. "Knife looks new." "It is. Traded a dozen eggs for it. I'm trying to make a duck for Vadim." "Your son's one. Won't recognize a duck."  "I know. But if I start practicing now, by the time he's old enough to want a toy, I'll be able to make one. You'll understand when you have kids." "Working on it." "Speaking of that, how'd it go with Arhip?" "Greedy little poo poo. But works well with furs."  Bogdan put everything away, and the pair rode home. "I managed to get some solid thread for your work. Dunya said the old stuff didn't hold the furs together very well." "Thanks. I'll pay you back. Both of you."  "Nonsense, Osya, family first! And hey, if everything goes well, the family will grow a little larger, eh?" "Yes. If it goes well."  Osip opened the sack and looked over his processed furs in detail. Arhip's work was stellar: the squirrel furs were soft to the touch and ready to be stitched together. A few more trips, and his gift would be ready.  "By the way, everyone's been talking about the war", Bogdan piped up. "With the English, yes. Arhip mentioned." "What'd he say?" "Something about the French and Turkey? Not sure. Arhip's full of poo poo."  "I heard that the English are fighting in Italy so that the Egyptians stay in Turkey." "What nonsense. Do the city folk think the Tsar a fool? What kind of a war is that?" "Nonsense or not, if more recruitment's coming..." "Yeah."  Though they'd never say it out loud, neither brother wanted to end up like their dad. For them, the army was a death sentence, like Siberia. It just took a while. "You should be fine, though. The barin needs you around for the hunting." "Maybe. You're useful too. You do the trading."  "I suppose. Let's avoid getting on his bad side, just in case." The pair rode in silence, ruminating on the potential draft. Not a lot of serfs would be called up, but the barin would decide who gets to stay home, and who gets to be a soldier for the next 19 years.

|

|

|

|

Got a bad feeling about this for the guy the barin knows is a good shot.

|

|

|

|

GunnerJ posted:Got a bad feeling about this for the guy the barin knows is a good shot. Same. Stay safe, brothers

|

|

|

|

Surely nothing bad will happen to the serfs. They are after all subjects of the wise and just Tsar, who has their best interests at heart.

|

|

|

|

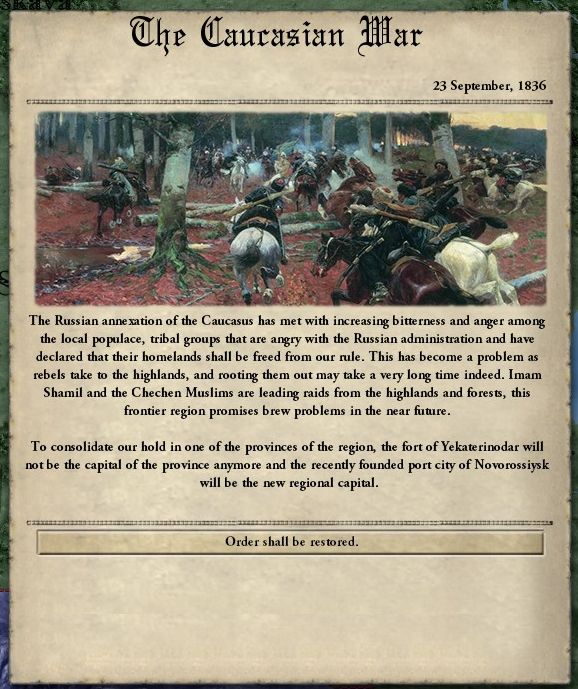

GunnerJ posted:Got a bad feeling about this for the guy the barin knows is a good shot. Why send away your best shot to die in some silly war in the Caucauses when you can just send that layabout that hasn't made you money in a decade?

|

|

|

|

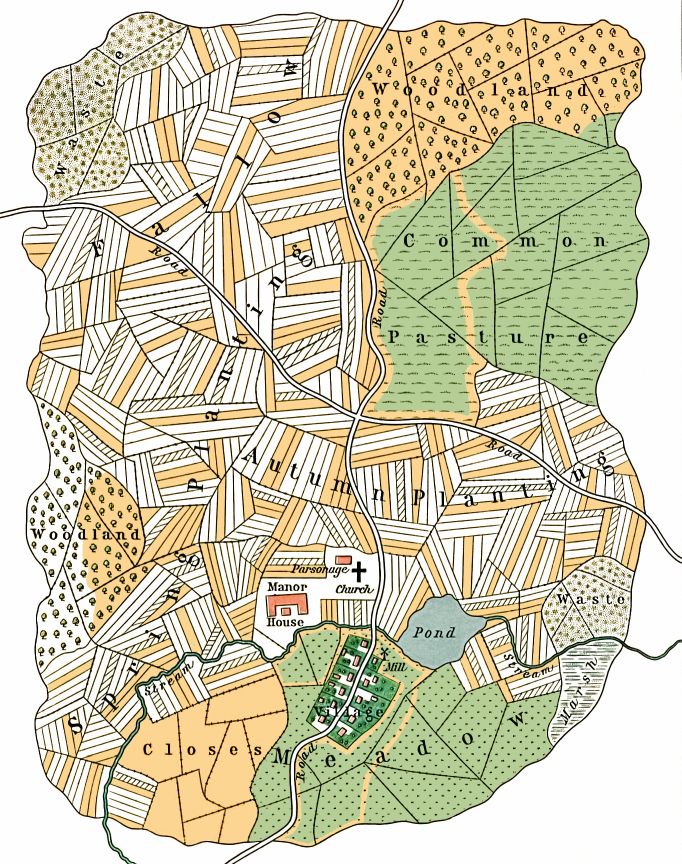

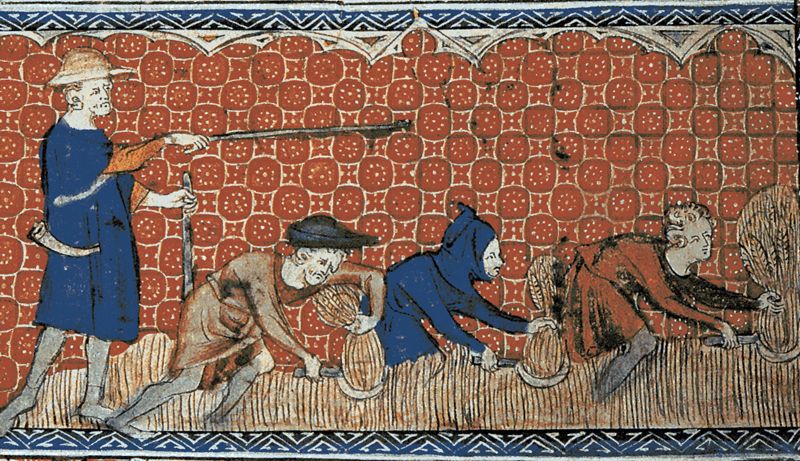

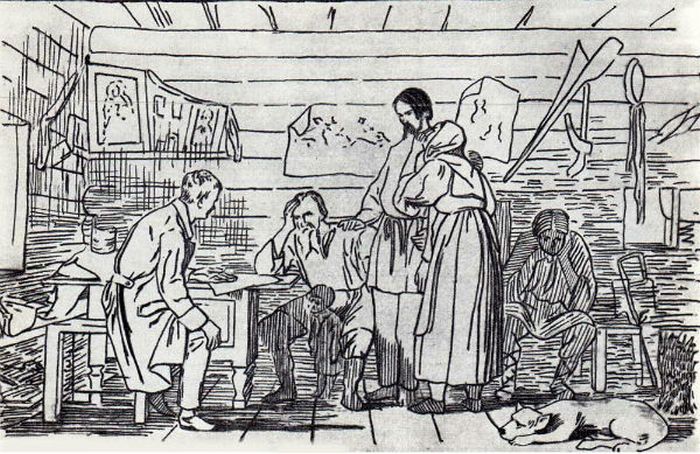

Supplemental 2 - A "Brief" History of Serfdom in Russia The situation our small family found themselves in 1836 wasn't created overnight, it was a gradual process that took centuries. But how did this medieval institution end up existing on such a grand scale in 19th century in the Russian Empire, when it fizzled out in western Europe in the Late Middle Ages?  A plan of a typical medieval manor in England - William R. Shepherd, Historical Atlas (1923) The mustard strips of land are the lord's personal land, the striped ones are owned by the church. Everything else is rented out to the peasants. So let's talk about manoralism (segneuralism). The segneural system was widely practiced in the Middle Ages across western Europe, and broke up land owned by an individual lord into strips that were then farmed by individual peasant families. Since no lord (or priest) would ever actually work, all the labour that turned the ground into something valuable either directly (by growing wheat, barley, tobacco, etc.) or indirectly by feeding animals with food grown on it (milk, cheese, eggs, etc.) was done by peasants. However, as far as the lord saw it, all of the land was his, and the peasants owed him for using it, usually in product. Say you, as a peasant, managed to grow twenty sacks worth of grain on the tract of land you worked on over the year. Two of these would go to the church, because you wouldn't want to upset God. One of these would remain for next year so you can plant more. Two of these would be eaten either directly (you mill it into flour and bake bread) or indirectly (you trade it for other food at the local market) by you and your family. You're left with fifteen sacks. The lord takes anywhere from five to fifteen of these as taxes, leaving you to go gently caress yourself, or get stabbed by the lord and his troops. Animal products (milk, eggs, meat) worked the same way.  Feudal Lord and Peasants - Unknown, Queen Mary's Psalter (~1310) This system included both serfs and free peasants, both of who paid rent to the lord for the privilege of feeding him and his layabout lifestyle. The difference was that the serfs were attached to the land or the lord directly, which meant they could not leave the land unless forced to. The extent to which this made them the lord's property varied wildly depending on the time and place, from "almost like a freeman, insured against corporal publishment" to "slave in all but name". The segneural system was also the chief land-use system for peasants in the Russian Empire. The reasons serfdom appeared in western Europe were complex, but I will try to generalize to compare it with the Russian style of serfdom. Generally speaking, after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and its ability to direct resources across its vast area, power became very local. Whoever could get a bunch of dudes on horses to go stab someone else for them became the local lord. While there were other things that produced value, and thus power to whoever controlled it (mines, important trade route nodes, local artisans), land made sure that people didn't starve. It was by far the most plentiful, and the most important source of value. You can't eat copper, and neither can the miners that actually get it out of the ground. Thus, whoever controlled the land could feed their troops, who could get more land, which could feed more troops, and so on, and so on. Note that "controlling" here means both holding the land itself and getting peasants to farm it - land without peasants is useless. As these petty fiefdoms expanded, slowly growing into duchies and kingdoms with complicated oaths of loyalty between the smaller lords and the larger ones, the nobility took more and more drastic steps to secure the peasantry. This culminated in laws that tied peasants to the land, turning them into serfs. (This process of attaching peasants to the land started happening in the 3rd century CE long before the Western Roman Empire collapsed. The coloni - tenant farmers - slowly lost their rights until a sort of proto-serfdom emerged. However, most land was still farmed by tenants that could theoretically leave, with something akin to sharecropping. Mass serfdom only really took off in western Europe in the Middle Ages)  Outbreak - Käthe Kollwitz, "Peasants' War" series (1906) So how did this practice die out? Well, eventually, owning land and extracting value from it by having peasants grow food stopped being the greatest possible source of power. Individual landholders that used food gained from "their" lands to feed small armies started getting outclassed by both the centralizing monarchies and the growing class of traders who could fund their own mercenaries. On top of that, following the Black Death, there were a lot fewer peasants left, meaning those who survived could bargain for better conditions, which they politely did in England, France, and Iberia. Non-farming production also grew to the point where a lord could make a lot more money with a manufactory than with an estate, and manufactories needed free peasants to But what about Russia? Well, let's take a look at a few critical differences between western Europe and Russia. For starters, for quite a while, western Europe was united by the Roman Empire, with its legal system and proto-serfdom heritage. More than 400 years passed between the time the Western Roman Empire finally fell (traditionally 476, when Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus) and the Kievan Rus started (traditionally 882, when Oleg the Seer took Kyiv and set his capital there). By the time Kievan Rus collapsed into the clusterfuck of Rurikovich principalities (12th century) that somewhat resembled Western Europe post-Karling, nothing resembling a centralized state has even existed for long enough to build institutions. On top of that, there is a very important factor here: the climate. The European parts of Russia are colder than western Europe, meaning that growing food there is much harder. Remember our example of growing 20 sacs worth of grain during the year? Half it. One sack goes to the church, one to sow next year, two to eat with your family. Out of the remaining six, the pomeschik takes three to six. Moral of the story: gently caress you, starve. Anyway, the Grand Moskva Knyazhestvo (principality) more or less united the shattered Rurikovich principalities (and the Novgorod republic) by the late 15th century. By this point, there were a few categories of peasants: free peasants (free landowners, communal peasants), smerds, zakups, and kholops. Smerds were controlled directly by the knyaz ("prince") - the ruler of a given principality - and could own land, which they could pass onto their sons. Killing someone else's smerd was considered destruction of property and carried a fine. Zakups were debt farmers: people who sold themselves into debt and had to work it off. Unlike all other non-free peasants, they could not be beaten. Kholops were full-on slaves, usually taken in raids, or were zakups that tried to run away. Killing a kholop was also considered damaging property, and kholop children were born kholops (equal to cattle giving birth in legal documents).  Tsar Ivan Vasil'evich the Terrible - Viktor Vasnetsov (1897) After uniting the Rurikovich lands and beating back the Golden Horde, the Grand Principality was reformed into the Russian Tsardom. This process took a few decades, and encompassed the reigns of Ivan III (the Great) and Ivan IV (the Terrible). One of the major reforms Ivan III did, expanded on by Ivan IV, was establishing the pomestye ("estate") system. Under it, people that served the Grand Prince/Tsar well in war or matters of state were granted land with peasants on it in lieu of payment, becoming pomeschiks ("estate holders"). There were first granted for life, but eventually made inheritable. Most of the peasants on this land were free, though their rights were immediately limited: they could now leave the pomestye and move only once a year, during the week before and the week after Yuri's Day (November 26th). Provided they paid their taxes. At the same time, smerds and zakups were removed as a category and rolled into kholops. Two types now existed: regular kholops, taken from captives in war, with their status inheritable; and rostovye ("growth") kholops, who sold themselves into slavery to pay the interest (growth) on their debt. Rostovye kholops were not considered serfs, their debt was wiped clean on death, and they could still buy their freedom. The pomestye system by the late 16th century was weird one: newly-minted nobles could also own their own land that was worked by their personal kholops, on top of tsar-granted pomestye. However, the peasants that worked the pomestye could not be used to work the other land: they were independent subjects of the tsar, and not the barin's ("lord") property. Unfortunately, things only go downhill from here. In 1597, the tsar signs an edict that establishes beglyy sysk ("runaway search") - a system where if a peasant runs away outside Yuri's Day without paying that year's taxes, and is found within five years, they are to be forcefully returned to the pomestye. At the same time, Yuri's Day is suspended temporarily (and officially cancelled a century later). The only way for a peasant to leave a pomestye was to run away and not be caught for five years. This bullshit was tightened after the Time of Troubles and the ascendance of the Romanov dynasty. In the early 17th century, the beglyy sysk is first increased to fifteen years, and then to infinity, and now covered all peasants that have left the pomestye outside Yuri's Day (which was suspended), even those that have paid their taxes for the year. The pomeschik could now track down any runaway peasant or his descendents, and forcefully bring them back, fully fixing them to the land and making them krepostnye (serfs, lit. "attached") The only remaining rights they had that separated them from kholops were: the ability to petition the court over mistreatment, they could not be evicted from the land and turned into kholops (who were reclassified as dvorovye - "of the yard", landless peasants who did whatever the lord wanted), and if they were beaten to death, the barin owed the family of the deceased a fine. They were still attached to the land, and could not be sold without it.  Peter I on his Deathbed - Ivan Nikitin (1725) Until Peter I (the Great), the westernizer and reformer. Peter I's great reforms put him up against the established old nobility (including a myriad Rurikoviches still running around), who were very comfortable with their privileges and influence. To combat them, he created new nobility (later formalized in the Table of Ranks) to have his back. And what did the great reformer use to secure their loyalty? Why, grant them power the only way power was granted in Russia: by giving them peasants. gently caress it, let's just sell them without land, why not. Thus a new class of nobility was born, fanatically loyal to the now Emperor of the Russian Empire, built through serfdom. Oh yeah, Peter I also essentially removed the kholops as a class, I guess? This wasn't done out of any great love for people, he was a oval office like any king, these weren't people to him. No, what happened was Peter called for a census for taxing nobles according to the number of souls they had on their pomestye. To dodge taxes, a ton of nobles registered their krepostnye as dvorovye, since those weren't counted as taxable souls. Once he found out about this particular scam, he forced a second census through, counting all peasant souls the same, erasing the last little bit of difference between them in practice. By the mid 1700s, this was certified by his successors, who nationalized all souls owned by traders, priests, cossacks, and old nobility, turning them into krepostnye owned by the Tsar Emperor. The new nobility thus became the only possible owners of humans in the Russian Empire outside the all-powerful head of state. The final nails in the coffin happened in late 1700s. In 1747, pomeschiks were allowed to sell their krepostnye to be recuited into the army on behalf of anyone else. In 1765, krepostnye could be sent to Siberia to be worked to death in labour camps. In 1767, they were strictly forbidden from petitioning the Tsar Emperor about mistreatment at the hands of their pomeschik. By the time our story takes place, there were a few weak-rear end edicts "protecting" the krepostnye, such as one that forbid splitting up families without also selling land. In practice, pomeschiks just placed an ad in the newspaper that said "renting out a man", but everyone knew exactly what was happening. On top of that, the practice of mesyachina ("monthly") started becoming widespread. Under mesyachina, the pomeschik took all of the krepostnoy's property, including their home and food, and worked them around the clock. This meant that he could no longer work his rented plot of land, and grow food to not die. In return, the barin occasionally fed him.  Christ in the Desert - Ivan Kramskoy (1872) The krepostnye could be beaten, including to death, could be exiled to Siberia with confiscation of everything they owned, could be recruited to the army to serve for decades, and could by this point be worked around the clock. They were personal property of the pomeschik, and could be sold or given away at will. Their children were born krepostnye and could not escape that fate. Slavery. I'm describing chattel slavery. For 23 million people in a country with a population of 67 million. I loving hate the Russian Empire.

|

|

|

|

When I woke up this morning, I did not expect to get depressed while reading LPs on Something Awful.

|

|

|

|

Finally got around to reading that new-ish Victoria LP that's been sitting in my bookmarks for a while and whoops definitely should have done that sooner. Good LP, this whole empire thing sounds like it's going great and we've got a bright future of watching our scores go up ahead.

|

|

|

|

Between this and Revolutions I am very, very glad that the Russian tsar was overthrown

|

|

|

|

Kayten posted:The krepostnye could be beaten, including to death, could be exiled to Siberia with confiscation of everything they owned, could be recruited to the army to serve for decades, and could by this point be worked around the clock. They were personal property of the pomeschik, and could be sold or given away at will. Their children were born krepostnye and could not escape that fate. Jesus

|

|

|

|

Can't wait for those POP numbers to go up!

|

|

|

|

Slaan posted:Between this and Revolutions I am very, very glad that the Russian tsar was overthrown Don't worry, we're not there yet. Russian history works on a simple principle after all. Namely: 'and then it got worse'

|

|

|

|

It's better than chattel slavery bc they make your soldier number goes up

|

|

|

|

Good news and bad news. Bad news: *gestures vaguely at everything *. This LP is, for the lack of a better term, depressing. I'll be honest, given the current political climate, I'm having a hard time approaching it. Thus, it's on hiatus for now. Good news: To write something that is NOT depressing, here's a Stellaris LP where we're playing an ancom version of the US in a galaxy populated with other versions of America. It should be much more upbeat. Once that's done, or dies out, I'll be back to SerfLP.

|

|

|

|

Guess what's back.

|

|

|

|

1.3. - New Bonds Vasiliy Bochin - News of a Recruit Levy (1860) 1841 - December 5th - Sergeevo pomestye, Nizhegorodskaya Governorate The December winds swept across the fields around the priest's house next to the small church. A small group huddled together for warmth, covering their faces to protect against the snow drifts. Marfa stood apart from them, twirling in her new squirrel fur coat. "Fisa, look how it shines in the sun!" "It's very pretty, Marfa. Osip worked hard for it." "How long was he working on this? It must've taken ages!" Bogdan mumbled under his nose. "drat near two years." "It's so romantic! I didn't know the oaf even cared about me!" "Osip's not good with words", Yelisey said.  Another round of yelling was heard from the priest's house. "I'm not marrying all of my blood to serfs!" "As if I've had callers come from the city! He's so unreasonable!" Marfa said, stomping her foot into the rough snow. "Daddy needs to let it all out, he'll tire eventually", said Fisa. "Remember my courting? Three days he yelled", said Yelisey.  "You're all he has left, Marfa", Dunya said, rocking her daughter, all wrapped up against the elements. "I don't know what I'm going to do when someone's going to come to take Matryona away from me." Dunya poked at her daughter's rosy cheeks, cooing nonsense at her. Matryona's laughter jingled across the snow, an oasis of happiness in the pomestye. Dunya still wasn't sure how she felt about her husband, but her children were a different story. There were no doubts here, and there was nothing she wouldn't do for them.  She looked over at Bogdan, who was whispering something to their son, Vadim. He was three years old already, and was Bogdan's most favourite person on this earth. The pair were inseparable and conspiratorial, keeping boy secrets from the girls, and always doing something with wood. Their small collection of simple wooden toys was growing, though the very first duck remained Vadim's most prized possession. The boy had it under his rough coat, close to his heart, even as he sat on his dad's shouders.  But Marfa had no children, and today was, after all, about her. "I'm not a child, Dunya, I'm getting on in years. I don't want to get married at 25 like an old maid!" "Speaking of children, Fisa, where's Kuzma?", Yelisey asked. "I left him with mom, she insisted on trying to get him to sleep in plain view of daddy while Osip visited. I dont think it quite worked as planned." ---  Inside the priest's house, it did not in fact, work as planned. Kuzma, the priest, paced around the house, reading prayer after prayer, asking God to spare him the suffering of this suitor. Mariya patted the crying Kuzma, the toddler, as he laid on the straw arranged on a bench to make a poor bed, trying to get him to calm down. "Kuzma Matveevich, find your conscience, there's a child trying to sleep here!", she quietly, but firmly pressed at her husband.  The priest had none of it. "There's someone here to steal our child, Mariya Trofimovna, or have you somehow managed to not notice the insipid man with his hat in his hand?" Osip's beard betrayed no emotion. He didn't quite know what "insipid" meant, but Kuzma's tone suggested it wasn't a compliment.  The priest fell to his knees in front of his wife. "He's here to take our baby girl, Mariya Trofimovna. To take her and place her into bondage for all time." "Osip, could you give me and the father a minute?", Mariya asked. The hunter bowed and walked to the opposite side of the izba and stood by the icon corner. He crossed himself three times, and started whispering prayers, pretending really hard to not hear anything the couple were saying.  "Pull yourself together, Kuzya, you're in charge of the immortal souls for this entire pomestye. How would the barin react if he saw you whimpering like a child with a scratched knee?" "drat the barin! This is my grandchildren we're talking about!" "Kuzma Matveevich! Watch your tongue, you're a priest!" Kuzma nodded and quickly crossed himself.  "Now listen here. I know you love Marfa with all of your heart, but you know that she will never speak with you again if you deny her this, right? She was a willful child, and she grew into a willful woman." "He's dooming our little one to a life of bondage, Masha. Just like Fisochka."  "I know. And it weighs on my heart. But what else can we do? Neither of them have had any callers from Arzamas. Who else will take our poor daughter, with no dowry, and no name?" "Maybe the Nikolo-Vyazheskiy -"  "The monastery?! Did my daughter find some noble blood in her veins when I wasn't looking? Do you have some connections with the Synod you haven't told me about?" "I don't -" "And you would deny me grandchildren for this?" Kuzma noticed that Mariya kept absent-mindedly stroking the toddler's hair, but has wisely decided to say nothing.  "Yes, this is far from ideal, but under the circumstances, things could be a lot worse. Osip's a fine man, reliable, and if the worst comes, knows how to keep his family fed. And he loves her! Did you see that coat? You think he bought it like some fancy lord?" Kuzma nodded. "It is a fine coat." "And the man's family? The whole pomestye loves Bogdan, and we practically raised Avdotya ourselves. They're lovely people."  Kuzma sighed and stood up. "You're right as always, Mariya Trofimovna." He turned to the hunter and coughed. "Osip!" Osip nodded as he turned around.  "Do you swear here and before the Lord your God to always take care of Marfa Kuzmichnina, to love her, and to be the best husband you can be?" Osip does not hesitate. "Yes. Swear by the Lord." "Then may you two live long and happy lives." The two men shook hands, deadly serious. ---  The door swung open, and the little group fell silent. Osip and Kuzma walked out, saying nothing. A few moments passed, and the priest finally spoke. "I would like to announce that in the matter of the marriage of Osip and Marfa Kuzmichnina..." Nothing but the wind could be heard for miles around.  "I give my blessing to the young couple!" The group erupted into cheers. Marfa ran to the pair, first hugging her dad, then Osip, then both of them together. The hunter's smile was so wide that even his snow-covered beard couldn't hide it.  One by one, the group offered their congradulations to the couple, as Anfisa immediately started planning the wedding. Yelisey walked up to Osip last and shook his hand. "We're finally family, svoyak." Osip shook his head. "Always were."  The group headed for the priest's home when Osip spied a lone figure in the distance. A young boy from the pomestye ran like hell towards the church. It took him a few minutes, but he finally crossed the snow-covered fields. It took the rosy-cheeked kid as young as ten a few moments to catch his breath, but he finally broke the news to them. "The barin's calling everyone. There's a levy." ---  The closest thing the pomestye had to a public square was the clearing around the pomestye well. Though there were often a few people moving to and fro, it hasn't been this packed in at least a decade. Every man in the area was lined up, waiting for the barin's decision. Osip, Bogdan, and Yelisey were the last ones to arrive. They quickly joined the crowd and watched the barin as intently as the rest. A lot was on the line: 25 years is 25 years. Konstantin Aleksandrovich Gromov, the head of the Gromov dynasty, sat on a white horse in front of all the souls he owned. Mstislav Konstantinovich, his son and heir, was desperately holding onto the reins of his horse behind him, using every morsel of his will to imitate some semblance of sobriety.  Next to the pomeschik was a short middle-aged man in uniform, with a carefully managed mustache taking up a full third of his face. He was Andrey Petrovich Letov, Feldwebel of the Imperial Russian Army, and he hated his low rank, his soldiers, but most of all, the cruel indignity of having to herd peasants for his imperial highness. The Letovs were a small, but proud dynasty, and Andrey Petrovich was a small, but proud man. He has spent the past two months gathering serfs from all across the governorate for the recruit levy, and despised every moment of it.  "May we finally begin, Your Well Born?" "By all means, Lord Feldwebel. How many souls do we owe to the Army for this levy?" Letov looked through his notes. "A mere five this time around." "A whole five working men? Lord Feldwebel, you're bleeding me dry. Who will plow the fields?" "It's December, Your Well Born." "It won't be December for twenty-five years." "I apologize, Your Well Born, but I do not make the laws, I merely enforce them." "Dura lex sed lex, after all. Very well."  Gromov's horse trotted along the front of the crowd. From time to time, the pomeschik pointed at one serf or another, a drunk here, a sick man there. Four men were selected, and dragged to Letov's horse. One remained. "Have mercy, Your Well Born, I have to bring at least one strong man to the rota this week. How about..." The Feldwebel's finger picked through the crowd, before finally settling on Osip.  "Him!" Osip stepped forward. "This one? This one's the worst drunk of them all." Gromov's face very carefully showed complete contempt for the man. "Hasn't worked a full day in ten years! Nothing but another mouth to feed." "Are you certain, Your Well Born? He seems to be in good shape." "Most certain, Lord Feldwebel. Wouldn't last a year in the Caucasus. Perhaps this one, instead?" He points at Yelisey. "Now there's a strong one." "Hm. He looks old." "It's the wind, Lord Feldwebel. Makes them all look weathered." "Very well, this one, then."  The soldiers dragged Yelisey to the Feldwebel's horse as well. His eyes darted around in a panic, but by then, he knew better than to speak when those above his are speaking. He wouldn't be the only one punished. "That's settled, then. What do you say we give them a few hours to pack and say their good-byes, while we enjoy some well-deserved dinner?" "How kind of you to offer, Your Well Born. It would be rude to refuse." He whistled at his soldiers. "Watch these five. The barin and I will return in a few hours. If any of them get away, I'll have you all whipped." Their businnes concluded, the nobility rode off for the manor house.  Yelisey rushed towards his horrified wife. "I'll be fine. It'll be fine. I'll, I'll get someone to write. You can write back." Anfisa buried her head in his coat, holding him as close as she can. "It's not always war. I'll be back. Watch Kuzma grow." He gently stroked her hair, but she refused to move, gripping her husband tighter. Mariya Trofimova walked up the pair with Kuzma, the toddler in tow. Yelisey picked up his son with his free arm. "Dad's a soldier. You're the man of the house now. Watch mom for me." Kuzma didn't understand the words yet, and just babbled in his dad's arms. One by one, the family said their good-byes. Osip walked up to Yelisey last and shook his hand. "I'm sorry, svoyak." Yelisey shook his head. "Don't be. We're family."

|

|

|

|

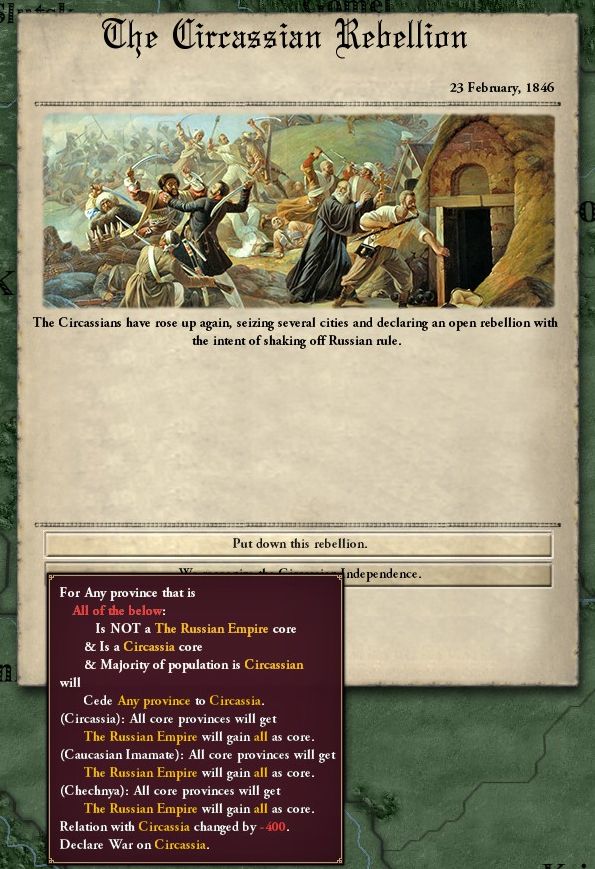

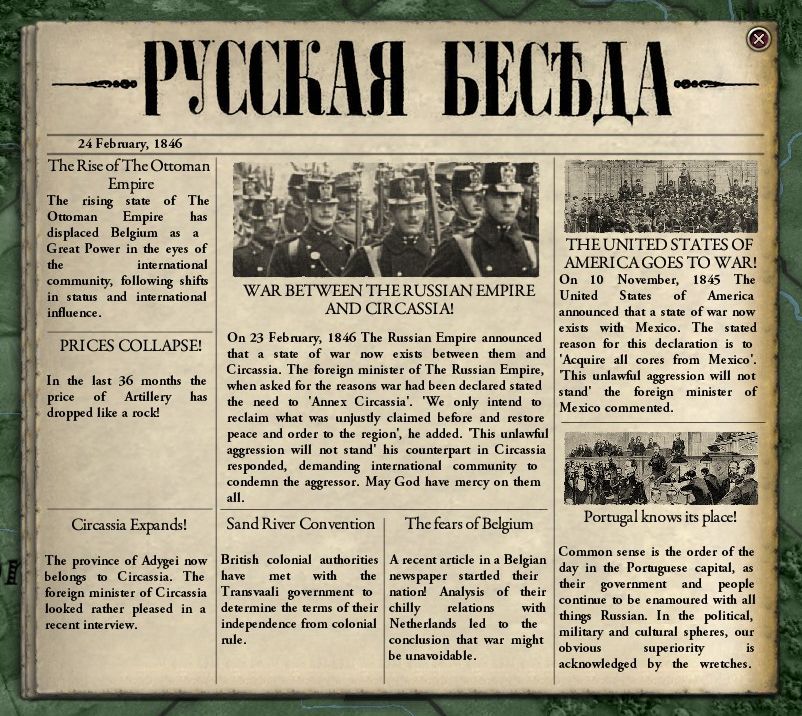

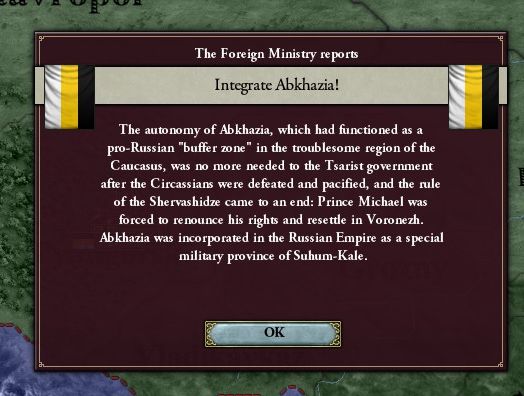

RIP Mexico, the Circassians, and also probably Yelisey

|

|

|

|

hell yeah let's go serfin glad to see this back

|

|

|

|

This rules glad to see it back.

|

|

|

|

SERF LP! SERF LP!

|

|

|

|

Really glad to see this back. It seemed like such a cool idea and I really liked the tone and cast, so I was crushed to see it go. So, as Gravity Cant Apple said,Gravity Cant Apple posted:SERF LP! SERF LP!

|

|

|

|

Serfs are back up! Woo!

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 16, 2024 21:57 |

|

This is a pretty cool LP.

|

|

|