|

Cessna posted:It's not insane given aircraft performance at the time it was initially stated. Multi-engine bombers had more power and could fly higher and faster than contemporary fighters. In addition, radar directed interception was not available.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 29, 2024 08:33 |

|

As I understand it, for awhile there the state of the air was to station a guy with a couple of gigantic hearing aids (of the "big cone whose narrow end is next to the ears" type) to listen for incoming aircraft, then to scramble your interceptors and hope they could get high enough fast enough to make a difference.

|

|

|

|

If you don't have radar then the bomber is almost certainly going to get through and get away unless they do something really dumb and arrogant like fly the exact same flight plan at the exact same time every day. over Belgrade Alchenar fucked around with this message at 17:07 on May 24, 2021 |

|

|

|

No one would ever do something that stupid.

|

|

|

|

You also have to understand “the bomber” to mean the strike package. The idea that every single bomber will hit its target is clearly ludicrous. Even the most primitive of AAA setups will get a few. But if you take it to mean that it is impossible to prevent all damage to the target it makes a lot more sense. Especially if you consider that some targets were previously considered both impossible to hit and politically ruinous if they were. Everyone badly overestimated how much civilian populations would be cowed by bombing, but in the interwar period “what if air dropped HE makes out capital resemble the trenches?” was a thing on people’s minds. PLUS in that interwar period a lot of people were thinking of the WMD potential of aircraft. There were people writing about how at the outbreak of another general European conflict the major cities would be blanketed by air dropped chemical weapons. “The bomber always gets through” looks like hubris when you look at it through the lens of the daytime bombing campaign ca Schweinfurt, but if you’re thinking in terms of WMDs even a couple slipping in becomes ruinous.

|

|

|

|

There are also advantages to having an air force be your primary armed force, especially for a place like the UK which is both cash strapped in the interwar period and has the memory of the horror of WWI in collective memory. The idea of having a relatively small force of airplanes that can act as a deterrent, even across the channel, without the enormous expense and manpower drains of additional warships (themselves vulnerable to aircraft) or a large standing army, was very appealing, especially without knowing the vulnerability of aircraft and overestimating the effect of strategic bombing. Of course as is always the case once you build up an armed force and give them the lion's share of defence spending, they will then be able to advocate for themselves and push their own agenda against the other branches. The Royal Navy would always be funded pretty decently simply because of the empire, but the army really felt the pinch up until WWII actually broke out (and even then, you could make an argument that the strategic bombing campaign was given too many resources compared to the results it got).

|

|

|

|

Panzeh posted:In addition, radar directed interception was not available. It’s really hard to overstate how much even the most rudimentary air search radar helps to produce a successful interception. I mean, there is a ton of doctrine and technology besides the radar itself, but when properly implemented, the whole package is a formidable defense.

|

|

|

|

BalloonFish posted:The one that comes to mind is the Battle of Cape St Vincent (the 1780 one), which was not only fought through a succession of nasty squalls but most of the action happened at night. Yeah, I couldn't think of a specific battle offhand but I was sure there were a few because there had to be SOME admirals crazy enough to go for it. Not surprised it's a late 18th century British admiral either, they really emphasized gung-ho "attack at all costs" thinking by then. And yeah, one thing we tell tourists a lot is that boats aren't faster than armies because they move faster, it's because they can go all night without stopping (if the wind holds). A pony express could beat a boat in a race handily, if you've enough spare horses. That's actually another way of finding fleets to fight - depending on where you are, if you set up messenger relays it's possible to sight a fleet and get word to your own in harbor in time to come out and engage. Didn't realize the effects of coppering on overall speed was so small, but as I understood it coppering's biggest advantage was in keeping ships out of drydock for longer and allowing them to maintain speed better over time due to slower underwater growth, right? The faster speed was just a bonus and all?

|

|

|

|

MikeCrotch posted:There are also advantages to having an air force be your primary armed force, especially for a place like the UK which is both cash strapped in the interwar period and has the memory of the horror of WWI in collective memory. The idea of having a relatively small force of airplanes that can act as a deterrent, even across the channel, without the enormous expense and manpower drains of additional warships (themselves vulnerable to aircraft) or a large standing army, was very appealing, especially without knowing the vulnerability of aircraft and overestimating the effect of strategic bombing. Had France not collapsed in 1940 then it feels intuitively likely that a strategic bombing campaign based from England ends up looking a lot more decisive.

|

|

|

|

Tomn posted:Yeah, I couldn't think of a specific battle offhand but I was sure there were a few because there had to be SOME admirals crazy enough to go for it. Not surprised it's a late 18th century British admiral either, they really emphasized gung-ho "attack at all costs" thinking by then. It was only 23 years since Byng was executed for "failing to do his utmost" - i.e. not fighting to the death against a vastly superior enemy with both a tactical and strategic advantage. That sort of thing will instill a gung-ho attitude in those that come afterwards. Voltaire was not really being satirical when he had a character note that "Il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres" (it is good to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others). Tomn posted:And yeah, one thing we tell tourists a lot is that boats aren't faster than armies because they move faster, it's because they can go all night without stopping (if the wind holds). A pony express could beat a boat in a race handily, if you've enough spare horses. That's actually another way of finding fleets to fight - depending on where you are, if you set up messenger relays it's possible to sight a fleet and get word to your own in harbor in time to come out and engage. Didn't realize the effects of coppering on overall speed was so small, but as I understood it coppering's biggest advantage was in keeping ships out of drydock for longer and allowing them to maintain speed better over time due to slower underwater growth, right? The faster speed was just a bonus and all? This is something I quickly realised when I began doing cruises on sailing boats - you may only be able to move at a brisk walk but you can do with constantly without great physical effort on your part. Walking 300 miles (carrying your food, shelter and equipment with you) is a major undertaking. It's a pleasant weekend's trip by boat. Yes, coppering's main advantage was that it allowed ships to spend much longer periods at sea without their performance (both in terms of speed and sailing ability) degrading to the point of uselessness. It did little to increase the maximum speed of the ships - they could just more dependably reach whatever their top speed was. I get the strong impression that, away from the drama of nautical fiction and the compelling historical narratives of frigate chases and strategic fleet maneouvres, ships generally loped along at a fairly constant 5-ish knots regardless of the weather if there wasn't a specific need to hurry. It's easier on the ship, the sails, the rigging and the crew if you aim for 5 knots, spread all your canvas when the winds are light and then reduce sail if the wind picks up to maintain that speed. Of course convoys and fleets always had to go at the speed of the slowest ship. Frigates could regularly crack 10+ knots and even first-rate ships of the line could be coaxed into double figures in the right conditions but it doesn't seem they were driven anything like that hard. And in a fleet it's no good having everything straining along at near-maximum speed, leaving your scouting frigates and sloops to only be able to travel a knot or two faster if they need to get ahead of, move around or catch up with the fleet.

|

|

|

|

SU-100 front line impressions Queue: IS-2 front line impressions, Myths of Soviet tank building: early Great Patriotic War, Influence of the T-34 on German tank building, Medium Tank T25, Heavy Tank T26/T26E1/T26E3, Career of Harry Knox, GMC M36, Geschützwagen Tiger für 17cm K72 (Sf), Early Early Soviet tank development (MS-1, AN Teplokhod), Career of Semyon Aleksandrovich Ginzburg, AT-1, Object 140, SU-76 frontline impressions, Creation of the IS-3, IS-6, SU-5, Myths of Soviet tank building: 1943-44, IS-2 post-war modifications, Myths of Soviet tank building: end of the Great Patriotic War, Medium Tank T6, RPG-1, Lahti L-39, American tank building plans post-war, German tanks for 1946, HMC M7 Priest, GMC M12, GMC M40/M43, ISU-152, AMR 35 ZT, Soviet post-war tank building plans, T-100Y and SU-14-1, Object 430, Pz.Kpfw.35(t), T-60 tanks in combat, SU-76M modernizations, Panhard 178, 15 cm sFH 13/1 (Sf), 43M Zrínyi, Medium Tank M46, Modernization of the M48 to the M60 standard, German tank building trends at the end of WW2, Pz.Kpfw.III/IV, E-50 and E-75 development, Pre-war and early war British tank building, BT-7M/A-8 trials, Jagdtiger suspension, Light Tank T37, Light Tank T41, T-26-6 (SU-26), Voroshilovets tractor trials, Israeli armour 1948–1982, T-64's composite armour Available for request (others' articles):  Shashmurin's career T-55 underwater driving equipment Oerlikon and Solothurn anti-tank rifles Evolution of German tank observation devices Ensign Expendable fucked around with this message at 15:38 on May 25, 2021 |

|

|

|

I see that the tank destroyer argument was in full throat between the users, designers and commanders even in 1945.

|

|

|

|

Alchenar posted:Had France not collapsed in 1940 then it feels intuitively likely that a strategic bombing campaign based from England ends up looking a lot more decisive. Hrm. It would have meant the Luftwaffe was also trying to bomb France. France's weaker aircraft industry would struggle to produce interceptors as fast as needed. They'd want the British to help out. That would have put some interesting strains on the alliance, since I think the Luftwaffe could still attack Britain (though not as easily) without control of France. I also doubt that bombing could be decisive without atomic weapons, but it would certainly have been more destructive.

|

|

|

|

Zorak of Michigan posted:Hrm. It would have meant the Luftwaffe was also trying to bomb France. France's weaker aircraft industry would struggle to produce interceptors as fast as needed. They'd want the British to help out. That would have put some interesting strains on the alliance, since I think the Luftwaffe could still attack Britain (though not as easily) without control of France. I think in a sustained conflict over a western front thats somehow static the luftwaffe's lack of true strategic bombers results in the pressure lifting off France (this is deep into fanfic though). If the front is convincingly static then the UK is probably more willing to transfer squadrons over, has more breathing space to train pilots, and its likely the tempo of sorties is much lower.

|

|

|

|

The French had placed a shitton of American aircraft orders as well.

|

|

|

|

Alchenar posted:Had France not collapsed in 1940 then it feels intuitively likely that a strategic bombing campaign based from England ends up looking a lot more decisive. thin göring's pegasuses could have easily kicked them out of the sky

|

|

|

Zorak of Michigan posted:That would have put some interesting strains on the alliance, since I think the Luftwaffe could still attack Britain (though not as easily) without control of France. Even with France out of the war, there were large regions of Britain that were effectively immune to the Luftwaffe. Using only German bases and having to fly through areas covered by interceptors based in France to even approach the target? I really don't see that working out very well.

|

|

|

|

|

Meanwhile a Germany that doesn't occupy France is having to contest the air over and around the frontline and doesn't get any waning of bomber streams coming from Western France or the Channel. The ruhr ends up being on the aerial frontline rather than deep behind german defensive belts.

|

|

|

|

Lawman 0 posted:That doctrine really blows my mind that it somehow got wide adoption. What's funnier is they had a second go at it a few decades later with the B-58 and XB-70.

|

|

|

|

Tomn posted:I will note however the spotting in an engagement is still probably pretty easy compared to land observation because we're talking about individual ships, as opposed to amorphous regiments, on what is essentially a flat, featureless plain while every vessel has their own high ground from which they can climb to get a better view of things, in a scenario where both fleets are going to spend hours maneuvering in sight of each other before contact - which, again, is liable to happen at very short ranges, like we're talking pistol shot range. Plus, decent weather is pretty likely because, well, they're sailing vessels and rely on the weather to move around - I'd have to check because probably there have been a few, but fighting a major naval engagement in the middle of a storm would be rare because of the sheer luck-of-the-draw danger involved, and even without a storm a very strong wind badly restricts options as the ship heeling over would cause the upwind vessels to be unable to fire their lower deck gunports since they'd be right up against or in the water with their available guns by default pointing lower at the water and thus having lower range, while the downwind vessels would be firing their full broadside at a higher angle and thus greater range. And in times of rain or poor visibility, without the ability to see other vessels an admiral's command and control over his own fleet would be badly restricted as well, relying as much as it does on flag signals, which means most commanders would be unlikely to be willing order a major engagement. As such, most naval engagements are likely to occur in conditions of good visibility - at least until the shooting starts and everything is obscured by gunpowder smoke except whoever you're dueling right this moment. On the other hand one of the most famous engagements involving two ships hammering away at each other in close quarters occurred in the Battle of Hampton Roads and despite all these factors--long engagement, close quarters, good weather, and so on--both sides believed they had won after having driven their opponent from the field. That's not to say that the engagement between the Monitor and Virginia was typical. But it also wasn't an isolated event--duels between shore batteries and river monitors in the American Civil War were often inconclusive and resulted in one side or the other coming to false conclusions about the state the other was left in, despite everybody being in full view of each other for extended periods of time.

|

|

|

|

Gnoman posted:Even with France out of the war, there were large regions of Britain that were effectively immune to the Luftwaffe. Using only German bases and having to fly through areas covered by interceptors based in France to even approach the target? I really don't see that working out very well. I was imagining the Germans staging out of Belgium or the Netherlands. You're probably right though. If they had the range to hit England at all, it'd be a small portion of it, and hence easier to defend. My concerns appear ill-founded.

|

|

|

|

Fray posted:The French had placed a shitton of American aircraft orders as well. Their most successful fighter was in fact an American one that arrived right before hostilities. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtiss_P-36_Hawk

|

|

|

|

Ensign Expendable posted:SU-100 front line impressions I'm curious about the Israeli armor article and the T64's composite armor.

|

|

|

|

Zorak of Michigan posted:I was imagining the Germans staging out of Belgium or the Netherlands. You're probably right though. If they had the range to hit England at all, it'd be a small portion of it, and hence easier to defend. My concerns appear ill-founded. They also had bases in Norway to hit the Northeast iirc

|

|

|

|

feedmegin posted:They also had bases in Norway to hit the Northeast iirc Yeah but those raids had to go in unescorted, which was only viable under the assumption that the RAF had been drawn completely into the London/SE area.

|

|

|

|

BalloonFish posted:Yes, coppering's main advantage was that it allowed ships to spend much longer periods at sea without their performance (both in terms of speed and sailing ability) degrading to the point of uselessness. It did little to increase the maximum speed of the ships - they could just more dependably reach whatever their top speed was. Does anyone have an illustration of early modern marine fouling? Are we talking about 20 cm clams sticking off the side of the thing, by the time they send folks down there to start scraping?

|

|

|

|

SMH that they didn't implement Tank Destroyer doctrine, Berlin would have fallen even faster!

|

|

|

SubG posted:I understand what you're saying and agree that there are a bunch of factors which would tend to reduce the effects of the sort of confusion I'm talking about. Sure but the american civil war, especially the naval bits, was very much a bunch of enthusiastic amateurs slapping each other. It's not the best counterexample.

|

|

|

|

|

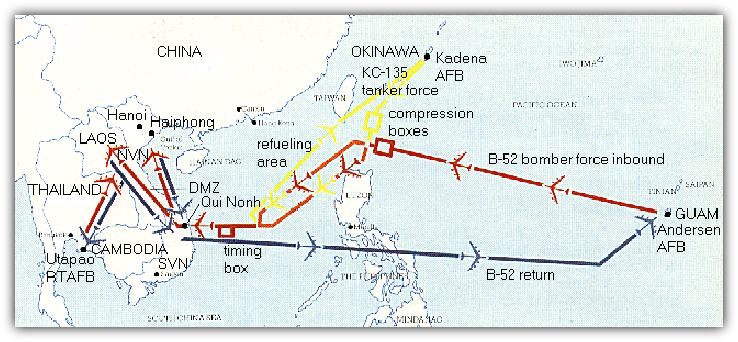

If I recall my American bombing campaign against Japan correctly, initially the US tried to fly B-29s at very high altitudes, in excess of 30k feet IIRC - this was supposed to put them way above flak and even fighters. The problem was that bombing accuracy was terrible at this height, and they started running into trouble with winds that would later be identified as the jet stream. They didn't want to send them within the 20k-30k band because then the B-29s would be vulnerable to high-altitude flak, and going in low would make them (even more) vulnerable to ground fire. So the story goes, Curtis Le May gambled/assumed that the Japanese did not have any anti-air designed for the "medium" altitude band of 10k-15k, and that they wouldn't be able to detect/aim well at night, so he sent the B-29s at night, at medium altitude, and it worked really well. Assuming I got all that correct (because I could be wrong, it's been a while since I was current on this), a question: from a technical standpoint, what would it take to make a gun suited to shoot within that altitude band? Or perhaps to phrase it differently: what is it about an anti-aircraft gun that determines how high it can shoot? and if you can shoot higher than a given altitude, why couldn't you shoot lower than that? To be clear, I'm not suggesting that Japan had the industry or the opportunity to play catch up even if they knew what to do, and even with the right guns they presumably still had the problem of having to aim accurately at night - I'm mostly interested in the gunsmithing/mechanical aspect of an AA gun.

|

|

|

|

SubG posted:I understand what you're saying and agree that there are a bunch of factors which would tend to reduce the effects of the sort of confusion I'm talking about. Eh, there's a reason why I specified early gunpowder - with wooden ships under sail it's a good deal easier to notice when the enemy is dismasted, when you've beaten five gunports into one, when the other guy is distinctly low in the water, when they're just plain not returning much fire, and perhaps most critically when they're capable of limping away, which is usually a sign that however badly they've been hit it isn't critical. Not to mention that, again, with short-range engagements with wooden ships it either ends with one ship striking and surrendering, one ship running away (which, again, is a sign that whatever damage isn't too critical), or something very dramatic and obvious like a fire or explosion that's pretty much a death knell for a wooden vessel. It's not just the nature of visibility here, it's also a question of the nature of the kind of combat you're looking at. Armoring, internal engines, explosive shells and long-range gunnery changes the equation a lot more. For the same reason determining how well you pounded a naval fortification is pretty difficult because, well, it's not a ship. Different factors at play in terms of how easily you can confirm that it's been pounded into uselessness. It's also worth noting that the importance of spotting damage differs from era to era too. As ships become larger, more expensive, and more mission-critical, there's fewer of them and knowing whether the Enterprise needs a few more months in drydock or if the Yamato had been successfully sunk can be potentially war-changing information. Conversely, if the Victory was sunk in battle then we've got a few dozen other ships of the line that do pretty much the same thing - it's a loss, but a not a critical one and in and of itself unlikely to change the balance of power between two battle fleets. If we wind back to the medieval era the vast majority of ships in a fleet action are small merchant vessels pressed into service as boarding platforms and the king doesn't really care that much about the state of individual ships, only whether he holds the field at the end or not (and back then naval battles are largely fought because you're trying to get your troops from A to B and the other side is trying to stop you, so the REAL measure of success is how many soldiers you still have left when all's said and done). On the whole, to go back to your original thought I'd agree that assessing damage in naval engagements was probably most difficult - and most critical - around WW1/2. Earlier on for most of human history it's both easier to do and less important.

|

|

|

|

Groda posted:Does anyone have an illustration of early modern marine fouling? IIRC a big problem wasn't clams, but wood-boring marine worms. My understanding is that it was more of a hull longevity thing that had some additional speed benefits than a speed thign.

|

|

|

|

gradenko_2000 posted:If I recall my American bombing campaign against Japan correctly, initially the US tried to fly B-29s at very high altitudes, in excess of 30k feet IIRC - this was supposed to put them way above flak and even fighters. The problem was that bombing accuracy was terrible at this height, and they started running into trouble with winds that would later be identified as the jet stream. Talking speculatively, but I imagine the issue is fusing. Guns can shoot to that height, but you need to fuse the shells to burst with the correct delay to hit at the correct height. At lower altitudes, the delay gets shorter, the precision required for the delay is greater (since the shell is traveling faster at that altitude) and also as the plane approaches the target, the amount by which the delay has to be reset increases too.

|

|

|

|

gradenko_2000 posted:If I recall my American bombing campaign against Japan correctly, initially the US tried to fly B-29s at very high altitudes, in excess of 30k feet IIRC - this was supposed to put them way above flak and even fighters. The problem was that bombing accuracy was terrible at this height, and they started running into trouble with winds that would later be identified as the jet stream. It may have been less about the guns not being able to hit them at all, and more about that altitude being a more palatable trade-off in terms of risk to effectiveness? As a rule of thumb, the higher-altitude an AA gun is, the lesser the sustained firepower you'll get out of it. You'll need a bigger powder charge to get the shell up to speed, a heavier warhead to compensate for lesser accuracy, so your rate of fire will be lower. Similarly, the whole gun will need to be significantly bigger, so you'll have fewer guns for a given budget of money/space/weight. For example, for the cost of a single high-altitude AA cannon in the 88mm calibre, you could get about four 25mm cannon, which combined can throw more metal into the air, and have a higher chance of scoring hits thanks to their much higher rate of fire. Of course with the trade-off being that these lighter guns simply cannot touch anything beyond ~9k feet. For that reason, AAA positions often had a mix of guns of various calibres, to be able to attack targets at different altitudes most efficiently. So, from the point of view of the plane, this divides the sky into certain altitude bands. Like you mentioned, above a certain altitude, you're completely immune from any AAA fire. Below that, you're in the range of only the enemy's heaviest guns. As you go lower, these will become gradually more lethal as they become more accurate. But then at some point you end up below a critical altitude threshold where you end up in the range of a whole new group of lighter guns, and you'll see the danger to your plane suddenly spike. Every time you enter the range band of a new type of gun, you'll find that much more weight of fire coming at you. There's also a difference in whether a given gun is intended to have its shells explode in the vicinity of the target and damage it with shrapnel (more common with large-calibre, high-altitude guns), or if it has to hit the plane directly (what you'd see in lower-altitude guns of 40mm and below). So, for Le May that may just have been a risk-reward assessment: Beyond 30k, the bombers couldn't be hit, but they could hardly hit anything in turn. At 20-30k, they'd be in range of Japanese heavy guns, but their accuracy would still be quite poor. They'd take on a fair amount of risk for relatively little gain. But down near 10k, that calculus inverts: The bombers would still only be taking fire from the same group of heavy guns (albeit more accurately), but their bombing would be substantially more accurate.

|

|

|

|

Cyrano4747 posted:IIRC a big problem wasn't clams, but wood-boring marine worms. My understanding is that it was more of a hull longevity thing that had some additional speed benefits than a speed thign. It's absolutely a speed thing though.

|

|

|

|

So as a person reading this thread who is not very knowledgeable about Western Naval military history during the early modern, I feel like the debate here is "navies could leave an engagement with relatively weak intel about their opponent" vs "navies usually left those engagements with great intel about their opponents." And what I'm seeing in this historical debate is that the weak intel side presents, piecemeal, a bunch of historical instances of one or both sides of a battle leaving the battle with unclear or wrong intel, and the strong intel side dismisses these as either exceptional and out of line with a first principles derived theory. So I guess I'm saying - what are the historical instances of a naval battle where a side has clear, accurate reporting on enemy forces?

|

|

|

|

Tulip posted:So I guess I'm saying - what are the historical instances of a naval battle where a side has clear, accurate reporting on enemy forces? The cowardly Americans and their dishonorable methods at Midway

|

|

|

|

Step one: Define clear and accurate.

|

|

|

|

Xakura posted:It's absolutely a speed thing though. Sure, but up-thread we've got people citing that they only saw moderate speed increase. The explanation I've always read (and no, I cna't provide a source right now, probably some books I read a few years ago while doing a job that involved naval research) was that the primary benefit was in making it much harder for wood-boring worms to get into the hull, which was a major problem for ship longevity and the amount of time they could be at sea between drydock overhauls. The sheeting did help discourage other marine growth and helped with speed, but that wasn't the primary concern.

|

|

|

|

It's my understanding that naval vessels in the age of sail were regularly careened or dry docked to both perform maintenance under the water line and reduce build up of marine flora and fauna, so they would be relatively "clean" compared to that ridiculous posted example, and therefore the speed benefits would be relatively low.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? Apr 29, 2024 08:33 |

|

Cyrano4747 posted:Sure, but up-thread we've got people citing that they only saw moderate speed increase. Sure, but the speed thing upthread was more of a "max speed didn't increase" I thought? Which makes sense, it's not like it's drastically slicker than un-fouled wood. I would think the benefit on speed is more how long can you have a max speed capable hull. I didn't mean to downplay the woodworm thing though, royal navy (at least, probably a bunch of others) used sacrificial wood plating on hull bottoms to avoid having their ships just eaten up.

|

|

|