|

gradenko_2000 posted:https://twitter.com/StilichoReads/status/1788404861010170252?t=A6_UQ0CB4HaaGHk9ERJoTQ&s=19

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 30, 2024 13:12 |

|

drat never knew that 7 million people died in the battle of guandu

|

|

|

|

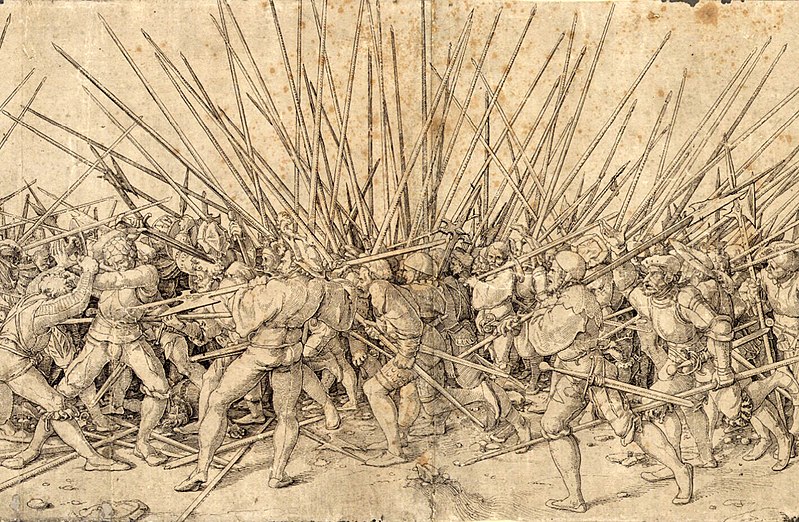

Reminds me of European chroniclers who would write that the losing side of a battle suffered 300,000 casualties and the winning side suffered 7

|

|

|

|

quote:Like most Black kids who grew up without diverse representation, Jordan Calhoun learned the skill of assigning race to fictional characters. Piccolo, Panthro, Demona, Ursula...he could recognize a Black character when he saw one.

|

|

|

|

DACK FAYDEN posted:as a white dude I absolutely cannot argue and he's four for four idk about Ursula since she’s just a cartoon version of Devine but yeah the others are obvious

|

|

|

|

Cup Runneth Over posted:Reminds me of European chroniclers who would write that the losing side of a battle suffered 300,000 casualties and the winning side suffered 7 This still happens all the time when people teach undergraduates. Livy, Plutarch and Herodotus were writing something like history, and provide insight into how the past was recorded and remembered, but they were obviously using numbers for emphasis. Very important = big. A battle that was important to the republic or the life of one of the figures involved, must have had a bazillion casualties. To a degree this happens with the history of Britain during the wars from the departure of the legions to Hastings. Because these were recorded in Welsh poems and Anglo-Saxon chronicles, several of them have passed into the Arthurian cycle, people believe they must have been these huge affairs. You know like Arthur's final battle, the Battle of Camlann, must have been like the fantastical Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Well, you look at how many men and horses these areas could support at the time, and the state of post-Roman logistics, and a big battle would have like 1000 guys on either side. It doesn't mean they weren't important, they were, they determined the government and religion of whole polities, figures who became mythological fought there as Dux or huscarls or whatever, but they were skirmishes compared to what we'd expect. To link this to nerd interests, this has led to debate about the army sizes Total War games should have to represent them, because Thrones of Britannia is the only game where, with the exception of Hastings, the TW engine can accurately depict the amount of people on the field 1:1. If a future game could have tens of thousands of little soldiers, it would be too big to accurately depict most of these battles.

|

|

|

|

Drunkboxer posted:idk about Ursula since she’s just a cartoon version of Devine but yeah the others are obvious

|

|

|

|

Just as an aside on the battle casualty figures, the victor having a lopsided amount of dead/injured is not always propaganda. In a lot of pre-gunpowder battles, the majority of casualties occur during a rout. The actual fighting is obviously dangerous and involves people getting killed, but in general when you are in ranks with your comrades, you are only at risk to a stray arrow or thrown missile unless you are actively engaged in the front rank. So a battle would be a slow burn of injuries/deaths in the front. Its only when something goes wrong, like being flanked, or that the front rank is overmatched and losing badly, that casualties mount and then get out of hand when one side breaks and then gets run down. Like in the early modern period, pike combat was mostly not a super high casualty affair when both sides are in ranks and stabbing at each other.  But if things went sideways, it could get horribly violent with immense loss of life and they specifically called it "bad war"

|

|

|

|

A Buttery Pastry posted:divine = black seems like i still have a lot to learn

|

|

|

|

caesar tells us his victory in Britannia after multiple stalemate encounters where the Romans were able to win the field but unable to destroy the enemy army was all due to finally managing to get only 30 equites over from gaul after his fleet got wrecked by a storm and prevented their initial arrival. 30 dudes on horseback facilitated the mass slaughter of the fleeing enemy army and ensuing widespread burning and destruction of settlements that several legions were unable to accomplish on foot.

|

|

|

|

WoodrowSkillson posted:Just as an aside on the battle casualty figures, the victor having a lopsided amount of dead/injured is not always propaganda. In a lot of pre-gunpowder battles, the majority of casualties occur during a rout. The actual fighting is obviously dangerous and involves people getting killed, but in general when you are in ranks with your comrades, you are only at risk to a stray arrow or thrown missile unless you are actively engaged in the front rank. So a battle would be a slow burn of injuries/deaths in the front. Its only when something goes wrong, like being flanked, or that the front rank is overmatched and losing badly, that casualties mount and then get out of hand when one side breaks and then gets run down. To tie this to nerds again, this is (part of) what light infantry and cavalry are for, and why their combat stats suck - they’re not supposed to fight the enemy line of battle head to head. They’re supposed to turn a retreat into a rout by harrying and harassing the enemy, including at the Grant Tactical or Operational level where they accelerate in army dissolving, during the pursuit phase. since most games don’t model, foraging scouting, securing lines of communication, delivering messages, etc. these units don’t have much use on the table top or in the Total War series. There have been several recent books saying that peltasts and other light troops were by far the most important part of Classical Greek armies, again undermined by Prussian historians projecting themselves backwards in time, with hoplites becoming the stars of the show. The Prussian disdain for light troops cost them again and again in the 18th and 19th centuries too, but they were imo addicted to orderly formations and complex parade ground manoeuvres. CN CREW-VESSEL has issued a correction as of 15:25 on May 9, 2024 |

|

|

|

yeah, if you're both on foot, then you're both running, and even with differences in lighter vs heavier gear and cardio, it's unlikely that troops pursuing will be able to inflict lots of casualties against troops running if you're on a horse, then suddenly it's a lot easier to catch up to and run down a man there are ways to defend against [charging] horses, which is then why you send your cavalry after the enemy has already been routed and wouldn't be in a position to fight back. And this is also why you have differences in cavalry, from heavy cavalry who are intended to charge against and break units that are still in fighting form, versus those dedicated to scouting, screening against enemy cavalry, and running down already-defeated enemies

|

|

|

|

Which again if you look at Prussia in the 19th century, they’re not very good at raising and equipping different kinds of cavalry, or even breeding different kinds of horses. You see this in all European militaries where the hereditary nobility goes into the heavy cavalry, and therefore the heavy cavalry is by far the most prestigious, most politically connected and most important. Well, you have a problem when modern history as a discipline, modern military science, and obviously military history, is all developed in Prussia during that time. Light troops are considered inherently inferior and inherently low class when these disciplines begin looking at Greece, Rome, the Diadochi etc.. You can find books written until, I want to say the 1990s, where Roman auxiliaries are considered inherently worse than Roman legions, even though all evidence points to them being integral to how the Roman military functioned.

|

|

|

|

the social wars were such an existential threat to Rome following the punic wars precisely because they leaned on their italian auxilliary allies so heavily. they radically reformed society and soldiery to appease and integrate the Italians and rapidly growing roman lower classes into the system at the very dear cost of fatally destabilizing the republic.

Real hurthling! has issued a correction as of 16:49 on May 9, 2024 |

|

|

|

CN CREW-VESSEL posted:Well, you have a problem when modern history as a discipline, modern military science, and obviously military history, is all developed in Prussia during that time. Light troops are considered inherently inferior and inherently low class when these disciplines begin looking at Greece, Rome, the Diadochi etc.. is that related to the tendency of to see the swap over to the lighter, more mobile kit of the comitatenses as a sign of institutional decline instead of an intentional adoption of new doctrine

|

|

|

|

practically every roman author in every genre from history to love poetry talks about how eurasian horse archers are the fastest and deadliest troops around. i've read way too many Scythian arrow metaphors for one lifetime so its extra funny that notoriously classically obsessed krauts cant handle the truth

|

|

|

|

CN CREW-VESSEL posted:Which again if you look at Prussia in the 19th century, they’re not very good at raising and equipping different kinds of cavalry, or even breeding different kinds of horses. Was that extended to the allies? cause those were "auxiliaries" as well. They were not just integral, the italian allies supplied troops literally identical to a roman legionary, as well as most of the cavalry. And then there was poo poo like the Jugurthine War that had access to auxiliaries as a major component of the conflict.

|

|

|

|

FrancisFukyomama posted:is that related to the tendency of to see the swap over to the lighter, more mobile kit of the comitatenses as a sign of institutional decline instead of an intentional adoption of new doctrine I was reading it has something to do with geometry, as in Prussian historians really liked formations and manoeuvre in terms of blocks and lines and that sort of thing. Since close order drill in the ancient and modern world was the domain of heavy infantry and cavalry, I guess a systemic understanding of war had to revolve around them? I can go look for quotes but it seemed almost like a caricature of German orderliness and fascinating with engineering, timing, intricate mechanisms and so on. e: I would imagine for 19th century European historians this is almost exclusively the army of the Principate in focus, since when Toynbee calculated the importance of the allies in his two volumes on the Second Punic War in the 1960's it was considered mind blowing and radical. ee: If someone wants to take a look, I'm thinking specifically about this gigantic block of Hannibal's Legacy vol 2.

CN CREW-VESSEL has issued a correction as of 21:35 on May 9, 2024 |

|

|

|

CN CREW-VESSEL posted:To tie this to nerds again, this is (part of) what light infantry and cavalry are for, and why their combat stats suck - they’re not supposed to fight the enemy line of battle head to head. They’re supposed to turn a retreat into a rout by harrying and harassing the enemy, including at the Grant Tactical or Operational level where they accelerate in army dissolving, during the pursuit phase. I'm going to push back against this on several grounds. First, we know well that light infantry did serve and function well on ancient battle lines as independent units. In the Hellenistic combat system, light infantry, most famously Cretans, would be deployed to manage a length of the line independently and generally served at this function somewhere between "fine" to "excellently." Again Cretan light infantry were a sought-after resource for all of the Hellenistic states as a valuable combat arm, not exclusively for their function off-battlefield. On a smaller scale, the Battle of Lechaeum has the (notionally) finest heavy infantry of the Classical Greeks (Spartiates) get utterly loving bodied off the field by Athenian skirmishers. The Macedonian victory at Callinicus was almost entirely down to their light infantry. And of course if we're going into gunpowder eras, light infantry were just invaluable for their ability to inflict more casualties than they took due to, well, the math of how deploying gunpowder weapons works. So for a wargame to model light infantry as 'not really intended for the battlefield' would be ungrounded in at least several eras of history, if not most of them. Second, I think laying this exclusively at the feet of Prussian biases requires ignoring Greek and Roman biases that exist in those much older sources as well. JE Lendon talks about this at length in Soldiers & Ghosts, that the Greeks in particular had, for reasons relating to the class politics of who wrote Greek histories and sources, a dramatic bias in favor of the hoplite, above and beyond the battlefield role played by hoplites. Ancient Greeks sources tend to be written by and honestly for men from the classes that would serve as hoplites in the army, and so they write sources that describe an army as made of hoplites and its only the more careful readings of the sources that tend to even notice that these armies were always combined arms affairs and not just blocks of elite infantry. The Romans are a little less silly about this, but its definitely a bias in their sources and I think largely attributable to the fact that Romans did in fact tend to win their battles most frequently by "the Roman heavy infantry dismantle the opposing heavy infantry straight in the face while the other arms of the army do lots of delaying/pinning/countering actions to keep the heavy infantry fight an exclusively heavy infantry fight." Anyway just because I think its interesting, I do think its interesting that Conquest: Last Argument of Kings does model one battlefield role that light units excelled at, which is screening and getting to the field first. If you read accounts of historical battles you can see that e.g. Velites are used to block maneuvering (and even vision) of the opposing army so that the heavier units can form & dress without getting assaulted. It's just one function and one part of using a combined arms set up in the ancient world, and its neat to see a game do that. (also the whole way total war does this is stupid as gently caress, top to bottom, I hope they stick to Warhammer because at least then it makes sense that you just summon a thousand demons from a warp portal between battles)

|

|

|

|

I should say that I'm basing this on Reinstating the Hoplite by Schwartz, specifically this section starting on page 13: book posted:RESEARCH HISTORY and then there are more references to Germans, including the core idea "One German scholar after another, driven by their primary interest in tactical forms and battle narratives, stressed that the disciplined hoplite and his well-ordered phalanx were the essential features of Greek warfare and the highest achievements of Greek military prowess... " in Brill’s Companion to Greek Land Warfare Beyond the Phalanx starting on page 1: other book posted:When we think about Greek warfare, we tend to think about the hoplite. The word conjures a specific image: a spearman decked out in bronze armor, carrying an iconic round double-grip shield and crested helmet, marching and fighting in a tightly ordered formation—the phalanx. While there may be other types of fighters around this hoplite phalanx, they are the periphery to his center. We can see this hoplite take pride of place in recent volumes on Greek warfare with titles like Reinstating the Hoplite, The Psychology of the Athenian Hoplite, A Storm of Spears, Men of Bronze, and Hoplites at War, all of which focus on understanding the hoplite as the key to understanding Greek warfare. Indeed, one of the most influential edited volumes in the subfield is simply titled Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience. We see the same iconic warrior all over representations of the ancient Greek world in popular media, from films like 300 and games like Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (2018) to a steady stream of historical novels, popular historical accounts, graphic novels, and YouTube videos on the wars of the Greeks in general and the Spartans in particular. I'll try to find the book (blue cover, if that helps?) with the detailed descriptions of Prussian military thought and specifically the focus on formation, manoeuvre, and drill, and how that influenced the historiography here. I did just finish a book on 19th century German classical education, I'll go back and check to see what it says about military matters. All of which to say, I'm not disputing the actual importance of light troops, I'm just relaying their sidelining because of the quirk of history where the focus on geometry as the core of linear gunpowder warfare was at its height in Prussia when those same Prussians started theorizing on the Greek and Roman militaries. CN CREW-VESSEL has issued a correction as of 22:23 on May 9, 2024 |

|

|

|

gradenko_2000 posted:

Mary Beard covered this lady on her podcast, as well as a few other random Romans that we have documents about. The tax collector one is my favorite personally.

|

|

|

|

How did i miss that Beard has a podcast?

|

|

|

|

CN CREW-VESSEL posted:

Yeah, during the period where battles were largely a case of massed bodies of musketeers lining up and shooting at each other, there was a huge advantage to being able to deploy in formation quicker and more efficiently than the other side, 'cos you could start firing while they were still getting their poo poo together. I read a biography of Frederick the Great and was struck by how much effort he personally put into developing and testing battlefield drills that would get his armies into position as fast as humanly possible.

|

|

|

|

CN CREW-VESSEL posted:I should say that I'm basing this on Reinstating the Hoplite by Schwartz, specifically this section starting on page 13: Ah, OK, my bad, it seems like you were talking about a historiographical issue that was related but not quite the same as the one I was concerned with. This is very cool! I do still sometimes run into the idea of "unsupported phalanxes" - JE Lendon for example thinks that there was a period of unsupported phalanxes at the early part of our historical records of ancient Greece that gave way to a more combined arms approach. The Prussians specifically have not been a focus of mine, I've been getting a bit more into Rome/Greece the last couple years, though I did recently read The Cutting Off Way and that would be a nice comparison to the Prussian Approach (the basic summary of The Cutting Off Way is that it describes warfare systems of the Northeastern Woodlands of North America during the 1600s and 1700s, which is probably some of the least heavy infantry friendly combat you'll find before exploding shells were generally adopted). Pistol_Pete posted:Yeah, during the period where battles were largely a case of massed bodies of musketeers lining up and shooting at each other, there was a huge advantage to being able to deploy in formation quicker and more efficiently than the other side, 'cos you could start firing while they were still getting their poo poo together. I read a biography of Frederick the Great and was struck by how much effort he personally put into developing and testing battlefield drills that would get his armies into position as fast as humanly possible. In the (really good! and open source!) "Reconstructing the Battle of Pydna" this was the authors' hypothesis per Livy about what happened to the Macedonian Leukaspides (White-Shields, half of the Macedonian's pike strength) - they were unable to form up in good order before II Legio crashed into them.

|

|

|

|

I hope you like long passages, because I can synthesize the two above, "The Prussian Model of Hoplite Battle" by Roel Konijnendijk in Classical Greek Tactics: A Cultural Historybook posted:The Prussians It goes on, there's about 60 pages on the Prussians, and several hundred on Greek tactics, which always refer back to them in some way. There's a large section on how American historians in the 1950's and 60's "for some reason" started borrowing heavily from German military thought, and so that's when this idea of Greek warfare really solidified itself in English language history, which is hilarious in a way because this is probably the most benign example of that phenomenon.

|

|

|

|

Drunkboxer posted:idk about Ursula since she’s just a cartoon version of Devine but yeah the others are obvious libs are not ready for the drag is minstrelry conversation

|

|

|

|

saw a guy parking a porsche with the vanity plate: 79 AD so i expected this to be some "fortune favors the bold" quipping pliny the elder cosplayer but when i said "like Vesuvius?" as i walked by and pointed at the car he ignored me so its probably just his birthday and initials or hes too cool for pedestrian captain obvious idk.

|

|

|

|

Real hurthling! posted:saw a guy parking a porsche with the vanity plate: 79 AD so i expected this to be some "fortune favors the bold" quipping pliny the elder cosplayer but when i said "like Vesuvius?" as i walked by and pointed at the car he ignored me so its probably just his birthday and initials or hes too cool for pedestrian captain obvious idk.

|

|

|

|

the year of the two fatal eruptions

|

|

|

|

Cerebral Bore posted:the year of the two fatal eruptions Lmao

|

|

|

|

Cerebral Bore posted:the year of the two fatal eruptions

|

|

|

Cerebral Bore posted:the year of the two fatal eruptions

|

|

|

|

|

In his Decretum, a tenth-century manual on canon law, Bishop Burchard of Worms directed priests to ask female parishioners if they had inserted live fish into their vaginas and kept them there “for a while” until they were dead, then cooked and fed them to their husbands to stimulate passion. He prescribed two years of penance on the appropriate fast days for a woman who had done this. Medieval theologians took the insatiable lusts of women very seriously: as a friend pointed out, the procedure was apparently considered two thirds as bad as accidentally killing one’s baby, which is discussed two items down in the Decretum, for which three years of penance were prescribed. In The Once and Future Sex, Eleanor Janega notes that the likelihood of medieval women having performed such a maneuver is “probably low…no matter how lacking their sex lives might have been.” Did Burchard believe it was a common practice? It is hard to understand the mechanics, just for starters. His Decretum was based on earlier sources, so he might have carried his stipulation to priests across from his exemplar unthinkingly, but medieval theologians were often concerned that ecclesiastics could put novel ideas of sin into parishioners’ heads during confession. For the question to have been asked, a husband’s being served an ill-used fish had to have been a legitimate concern. Janega’s book is wide-ranging—she takes something of a trawler net approach to the Middle Ages, covering a big area but not always managing to supply details or nuance. She illustrates, often hilariously, the ways women were oppressed, as indeed they were before and have been since, though the particular flavor of oppression has changed. In the medieval era, as now, women were expected to live up to impossible standards of beauty and were defined as “scientifically” different from men, even if the ideas of female beauty and biology were not the same. Janega also argues that women’s work was overlooked in the Middle Ages, as it is today. This is a claim that might irk some medievalists. Burchard, like many medieval thinkers, thought of women as “sex-addled” and “insatiable in their demands.” In this, Janega argues, “the medieval concept of women’s sexuality looks almost nothing like ours, except that it was considered wrong.” In his Etymologies—a seventh-century encyclopedia explaining human knowledge using (spurious) word origins—Isidore of Seville tells us that “the word femina [woman] comes from the Greek derived from the force of fire because her concupiscence is very passionate: women are more libidinous than men.” About two hundred years earlier, Saint Jerome likewise asserted that “women’s love is…insatiable; put it out, it bursts into flame; give it plenty, it is again in need.” A Latin poem from thirteenth-century northern France or England advises men not to marry and describes the average woman thus: quote:Her lustful loins are never stilled According to the humoral theory that underpinned much medieval thought, women were cold, wet creatures who gravitated toward men, who were hot and dry. In this, women were thought to be similar to cold-blooded animals like snakes that seek the heat emanating from humans. A thirteenth-century medical treatise took this idea a step further, stating that since women are inherently bad (what with the whole debacle involving Eve and the apple), a woman has a “greater desire for coitus than a man, for something foul is drawn to the good.” Many medieval writers seem to have agreed on what made these horny creatures sexually attractive to men. Texts that describe the appearance of the ideal woman have a lot in common. A number of them describe her as having blond hair, white skin, swelling lips, white teeth, and good breath. These qualities are depressingly familiar from our own day. But some aspects of medieval female beauty may surprise us. Thin, dark eyebrows and high foreheads were prized; the Roman de la rose praised women with “small mouths.” Geoffrey of Vinsauf was especially taken with a “neck like a white marble column,” while other writers compared the ideal neck to that of a swan, heron, or antelope. Matthew of Vendôme praised “dainty” and “modest” breasts, a view shared by Guillaume de Machaut, who liked them “white, firm, high-seated/pointed, round,” but—importantly—“small enough.” In Troilus and Criseyde, Chaucer describes Criseyde’s “brestes rounde and lite” (as well as her “armes smale” and her “sydes longe”). As for the belly, Matthew of Vendôme would have been horrified by the gym-sculpted abs many today prize, instead praising the ideal of a “luscious little belly” that protruded. As in the twenty-first century, in the Middle Ages the physical attributes considered beautiful were indices of wealth. A little potbelly meant you had leisure time, just as milky white skin meant you did not labor outdoors. In the thirteenth-century Old French Roman de silence, there is a scene in which a beautiful woman uses the juices of a plant to give herself a fake tan and disguise herself as a man of “low station.” Today, the converse among white people is a sign of being upper-class—tanned skin suggests leisure hours spent in sunny climes. Some writers showed an awareness of female sexual anatomy that might surprise modern readers. As far back as the thirteenth century at least one of them, Pietro d’Abano, had noticed the existence of the clitoris: he wrote that women could be aroused by having the upper orifice near their pubis rubbed; in this way the indiscreet, or curious [curiosi] bring them to orgasm. For the pleasure that can be obtained from this part of the body is comparable to that obtained from the tip of the penis. The eleventh-century Persian philosopher and physician Ibn Sina—known in the medieval West as Avicenna—wrote that men should caress a woman’s “breasts and pubis, and enfold their partners in their arms, without really performing the act.” This last clause reminds us that although some medieval men appeared to understand the mechanics of female pleasure, they nonetheless thought that the point of sex—the main “act”—was penetration, hopefully leading to procreation. Some writers suggested that for a woman to conceive she had to experience pleasure, which is heartening, but Janega justly cautions that this could have “dehumanizing consequences,” because it was thought that sex workers were “incapable of pleasure and driven solely by an interest in money” and could not become pregnant. The biological fathers of infants born to sex workers could thereby absolve themselves of responsibility for their children. Janega’s final chapter on women’s work is a feast of beguiling detail. Here the lives of ordinary women surface from the records in a way that is sometimes impossible in the earlier chapters on beauty and biology, where most sources are the literary and philosophical writings of a learned male elite. We’re told, for example, that in 1327 Alice de Brightenoch and Lucy de Pykeringe were sentenced to jail time for theft: both women allowed people to bake bread in their ovens for a fee, but they “falsely, wickedly, and maliciously” stole from their neighbors by siphoning off dough through a hole in a table, beneath which an accomplice was stationed. Here the argument is that women “were working at every level of society alongside or in partnership with men—and received almost no credit for doing so.” This is a large claim that I don’t really go along with. The picture is surely more complex. In her brilliant recent biography of Chaucer’s Wife of Bath, Marion Turner notes, for example, that there were new economic opportunities for women in the aftermath of the Black Death in Europe, when their right to trade as femmes sole was formalized, allowing them to run businesses, train apprentices, and take care of their own taxes. In other words, women were working for themselves. When women did work in partnerships with men, it is hard to know if they were given credit for what they did. So it pays to follow the money and examine transfers of property after death. Barbara Hanawalt’s work on peasant families in medieval England reveals that 65 percent of men made their wives executors. As she observes, “Most men leaving wills, therefore, trusted their wives to raise a family of young children and run both the house and lands.” That surely suggests confidence in what women could do. The same was probably true in other social classes. In 1448 the Norfolk gentrywoman Margaret Paston wrote to her husband in London and asked him to buy “1lb of almonds,” “1lb of sugar,” and “some cloth for gowns,” as well as “two or three short poleaxes” and “some crossbows.” She had been left behind on the family’s estates to raise the children, run the manors, and protect the properties from attack. Of course, even if wives had a degree of economic power and were valued by their husbands, that does not mean all women’s work was valued, especially that of women at the fringes of society. Sex work was disapproved of but still permitted in some law codes. Some writers even felt it was necessary. Both Augustine and Aquinas wrote that if sex work did not exist, men would have too much pent-up sexual energy, especially in urban areas, which could lead to rioting and violence. In London sex workers had to wear a special striped hood and were forbidden to live in the city itself. A statute of 1393 stated that they should “keep themselves to the places thereunto assigned, this is to say, the Stews [bathhouse brothels] on the other side of [the river] Thames, and Cokkeslane.” Janega writes that sex workers found outside the Stews risked being “stripped to their waist” as a “powerful form of public shaming,” though the Anglo-Norman source doesn’t seem to say this. It states that a woman would have to forfeit the “garnyment q[u]ele use per le dessus et le chaperon”—“the upper garment she shall be wearing, together with her hood.” “Garnyment” can mean “garment,” but it seems most often to mean an outer layer—the Middle English and Anglo-Norman dictionaries define it variously as “a coat, cloak, gown”—as well as armor or riding gear. So it appears more likely that the women, rather than risking public shame, stood to lose the cloaks and hoods that advertised them as sex workers, thereby temporarily impeding their ability to work. Janega also writes that when sex workers died they could not be buried in consecrated ground. I failed to find a source to support this idea. She cites the example of Crossbones Graveyard in London, which is a cemetery on the south bank of the Thames in an area where brothels were situated in the medieval period. But there is no archaeological evidence that the graveyard itself is medieval, and the first mention of it in written sources is by the antiquarian John Stow in 1598. Stow was a great collector and preserver of medieval manuscripts, so he is often a useful authority, but his sourcing of the information in this case amounts to vague hearsay: I have heard of ancient men, of good credit, report, that these single women were forbidden the rites of the church, so long as they continued that sinful life, and were excluded from Christian burial, if they were not reconciled before their death. The Once and Future Sex is great fun; I often snorted aloud while reading it. Janega’s discussion is joyously broad, but she skitters in places rather than digging down. “Women’s infidelity was a much larger concern than men’s,” she observes. Katherine Harvey’s 2021 The Fires of Lust: Sex in the Middle Ages adds nuance here. Harvey cites multiple examples from law codes that show how women were punished for adultery, yet she notes that court records from northern France and Flanders reveal that adulterous men, not women, were more often punished publicly: quote:In Arras (1328), five times as many men were fined for adultery, and in Tournai (1470) fourteen times as many men were punished. In late medieval Ghent, Bruges, and Ypres, the ratio for adultery convictions was approximately 80:20 male to female. The Once and Future Sex is not aimed at an academic audience. Literary scholars will not be surprised that “by analyzing literature, we can learn about the cultures of a period, what people considered important, and what made them tick.” Many would dispute the description of the Roman de la rose as a “novel” or the Middle English poem Pearl as an “epic.” There are several of these infelicities. Janega states that Alison, the protagonist of Chaucer’s “Miller’s Tale,” is “a woman who is willing to have sex with her suitor in a washing tub.” If Chaucer had described sex in a washtub, I would consider it my civic duty to quote it, but the text is clear: three tubs used for kneading bread hang from the ceiling, and once Alison’s husband is safely asleep in one of them (part of a scheme to enable the adultery), she and her suitor get out of theirs and steal off: “Doun of the laddre stalketh Nicholay, And Alisoun ful softe adoun she spedde;/Withouten wordes mo they goon to bedde.” (“Down the ladder stalks Nicholas and Alison softly sped down; without words they go to bed.”) There they engage in the “bisynesse of myrthe and of solas,/Til that the belle of laudes gan to rynge” (“task of mirth and of solace/Till the bell of morning rang out”). These are small details. Does it matter for the book’s argument that Nicholas and Alison were not in a washing tub? Does it matter that Pearl—a jewellike poem about grief—is recast as an epic? Almost certainly not, but there are places where this highly readable book opts for generalization over particularity, such as the suggestion that The Canterbury Tales is “a compendium of anecdotes about what was wrong with women.” That’s a view that omits “The Knight’s Tale,” with its idealized presentation of Emelye, or “The Franklin’s Tale,” in which a woman loves her husband so much that she prepares to kill herself when she is wooed by an unwanted suitor and then lists a catalog of twenty-one other faithful women from history and mythology who have stayed similarly true. This kind of reductiveness risks telling a blanket story of oppression. One example deserves unpacking. In a section on life at court, Janega writes that women’s expected duties included carrying the lady of the house’s train as she made her way to chapel and helping with embroidery. The men’s might include being called to war or sent on diplomatic missions. It’s a passage that doesn’t ring true. Juxtaposing embroidery with diplomacy and war and thereby casting it as something boring and contained repeats a tired patriarchal categorization of art forms that consigns needlework to irrelevance precisely because it was often practiced by women. A single work sees off this idea: the famous Bayeux Tapestry is a 230-foot piece of embroidery depicting the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. It depicts, as a recent work put it, “political intrigue, extreme violence [and] graphic nudity.” This is stitchwork that is big and sexy and political; it was most likely made by female artisans. Janega’s characterization here is at odds with what she says elsewhere in the book. “Medieval Europeans regarded embroidery as an art,” she writes, citing the early Irish law code Bretha im Fhuillemu Gell, which states that “the woman who embroiders earns more profit even than queens.” Why treat it with flippancy elsewhere? Her depiction of court women as creatures consigned to a life of sad train-carrying also feels misplaced. On February 20, 1440, Helene Kottanner, a servant of Queen Elizabeth of Hungary, took part in an audacious plan to secure the succession by smuggling the Hungarian crown out of the stronghold of Visegrád in a pillow. The crown was placed onto a sled and rushed to the queen; within hours of its arrival she gave birth to a baby boy, Ladislaus the Posthumous, who was crowned king of Hungary three months later. Kottanner almost certainly did carry her lady’s train and help with embroidery, but she also engineered a coup during a political crisis and recounted it afterward in a memoir. And it wasn’t only men who were “called to war or sent on diplomatic missions.” In a later part of the book Janega discusses Eleanor of Aquitaine, who negotiated with Pope Innocent II on her husband’s behalf and went on the Second Crusade. Janega might just as well have pointed to Urraca, the twelfth-century queen of Castile, described by multiple sources as “a leader of armies” in battles she had with Moorish forces, rebellious magnates, and her estranged husband, Alfonso el Batallador (Alfonso the Battler). Of course, these women were royal, so their experiences were unusual, but such examples are also important. As a reader of history, I don’t just want to read about drudgery and discrimination; I want to read about the women who gamed the patriarchal system as well. As a historian, I believe feminist history is at its best when it is twofold—delineating structures of oppression but also not allowing our own patriarchal biases to restrict our view, making us assume that women were voiceless and powerless just because traditional histories of the period haven’t thought their endeavors worth discussing. Janega is doing something important. To make the Middle Ages—a period so widely misunderstood—legible and exciting is vital work. My hunch is that historians do a disservice to the general reader when they shun complexity in favor of broad-brush abstractions, because the delight is in the detail. What specialist or nonspecialist is not enthralled to learn that Burchard of Worms seems to have thought women put live fish into their vaginas?

|

|

|

|

A very good post, I need to read her books and not just listen to her podcasts.

|

|

|

|

Alfonso the Battler actually ruled, so idk about the angle being taken here.

|

|

|

|

does anyone know if there is a good history of the cultivation of rice somewhere? im curious how it came to be such a staple grain vs stuff like barley, millets, wheat, etc

|

|

|

|

that poo poo dont grow in swamp

|

|

|

|

AnimeIsTrash posted:does anyone know if there is a good history of the cultivation of rice somewhere? im curious how it came to be such a staple grain vs stuff like barley, millets, wheat, etc sakuna: of rice and ruin

|

|

|

|

AnimeIsTrash posted:does anyone know if there is a good history of the cultivation of rice somewhere? im curious how it came to be such a staple grain vs stuff like barley, millets, wheat, etc Obviously don't take my word for it and I too want some more books on this but off the top of my head if you can grow rice with flooding in an area, it doesn't deplete the soil as much as other grains and you get more calories out of a given area. It's why there's a wheat/rice divide in china with wheat being in the north and rice in the south.

|

|

|

|

|

| # ? May 30, 2024 13:12 |

|

|

|

|